Writers love to talk about how fallible “the writing rules” are. The rules are made to be broken, we say. And proceed to do so. However, this rule — “show  v. tell” — is one that often gets the brunt of our wrath. But why?

v. tell” — is one that often gets the brunt of our wrath. But why?

For my part, I have benefited from the rules and think many of them get a bum rap. Of course, the rules of writing are more guidelines than they are formulas. Which is the problem: Novice writers often seek formulas to publication. Sadly, there is no formula to “showing versus telling.”

I like how James Scott Bell puts it in his piece “Exception to the Rule,”

Sometimes a writer tells as a shortcut, to move quickly to the meaty part of the story or scene. Showing is essentially about making scenes vivid. If you try to do it constantly, the parts that are supposed to stand out won’t, and your readers will get exhausted.

Which means there needs to be a balance between showing and telling; it’s not an either / or situation. A story that was all “telling” would be shorter, less visceral and less emotionally engaging. A story that was all “showing” would be incredibly long and overwrought, possibly meandering.

Thus, telling is a great way to move a story forward, to compact longer sections of thought or passages of time.

He got in the truck and drove back to town, all the while thinking about Janie.

This gets the protag where he needs to be in one swift sentence. However, perhaps this ride is more significant to our hero (and reader). If so, it would be better shown. Which means it might read better like this:

The scent of Janie’s perfume lingered in the truck. He wrung the steering wheel as he drove, wishing he could hear her little laugh again and see the sparkle in her sea green eyes.

Lately, I’ve been reviewing my copy of The Seven Laws of Teaching, by John Milton Gregory. It’s a classic, published in 1884. and still being reprinted. It’s also, I think, a valuable tool for writers. In his chapter, “The Law of the Learner,” Gregory writes this:

Knowledge cannot be passed like a material substance from one mind to another, for thoughts are not objects which may be held or handled. Ideas can be communicated only by inducing in the receiving mind processes corresponding to those by which these ideas were first conceived. Ideas must be rethought, experiences must be re-experienced. (emphasis mine)

So the teacher much address the mind and the senses; he must stimulate in his listeners, not just a mental process, but an experience. It’s not enough to tell the learner what to feel, he must make him actually feel it. Which leads Gregory to summarize:

The mind attends to that which makes a powerful appeal to the senses.

I think that this writing rule — show v. tell — is directly related to Gregory’s concept. So here’s my idea:

- Telling appeals to the mind.

- Showing appeals to the sense.

And appealing to the reader’s senses more actively engages her in the story.

Beginning writers tend to over-tell. Why? Because telling is a lot easier than showing; it involves less emotional machinations, less investment. Telling does not demand I really dig into my character’s psyche and put myself in his skin. I can simply say,

He was mad.

And that suffices.

All this to say, Show v. tell is an important writing rule, one that beginners and pros must respect. It’s not enough to just spout about the rules being made to be broken. A story needs both showing and telling. Which makes me wonder if a better interpretation of the rule is “Thou shalt know when to show and when to tell.”

Mike, thanks for this helpful, explanatory post. As a newer writer, I repeatedly heard that you always “show” and avoid “telling” like the plague. I tended to disagree but couldn’t seem to offer precise reasoning – especially if they were seasoned writers. You’ve done that beautifully here. Balanced is better. Thanks!

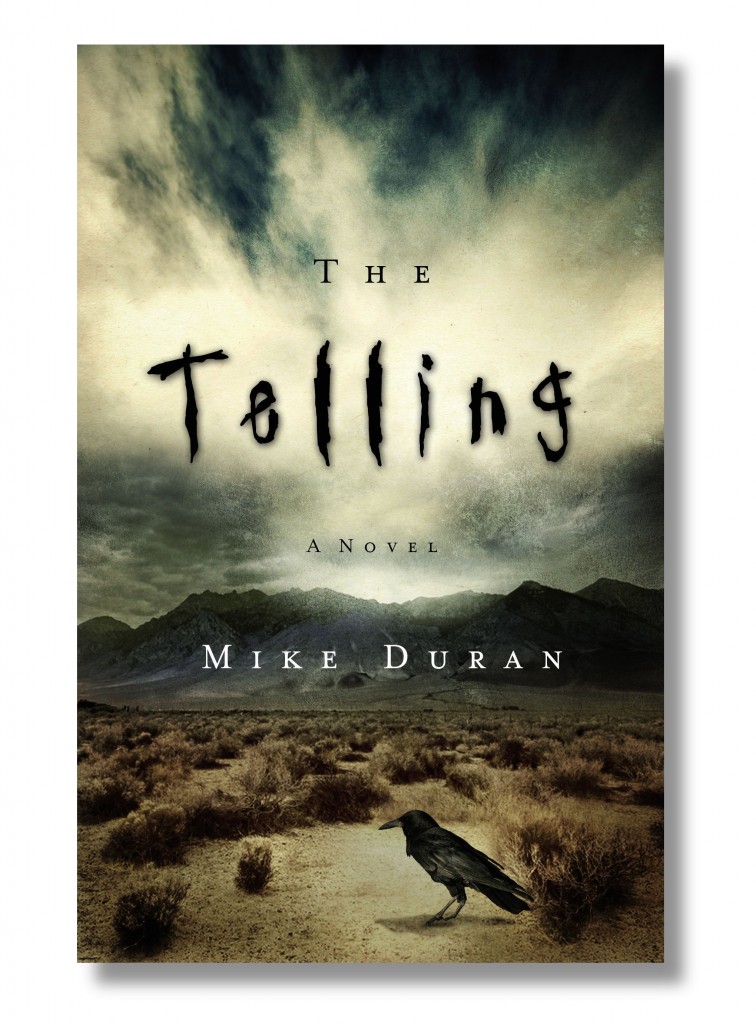

So does that mean your next book will be called “The Showing”?

Good one, RJB. Actually, I tried to do a lot of showing in “The Telling.”

RJB, that was funny.

Good points, Mike. I remember reading something about balance and what you talked about in “Self-Editing for Fiction Writers” back in 2006. They said essentially the same thing, that there are times to tell, to move the story forward over otherwise “boring” stuff not directly important to the story other than you need to get them from point A to point B, and times when you need to communicate the emotion of a scene or situation that is important to the story’s movement and plot.

And I’ve experienced both extremes. I’ve read stuff that was way too much telling that all emotion felt dead, and I’ve argued with a critique partner that no, you shouldn’t show everything in your story, there are time to tell.

I’ve gotten to the point in my critiques where I don’t say, “This needs more showing and less telling” to “This could use some more emotion” just to avoid the sometimes predictable backlash to “show, don’t tell.”

“Show, don’t tell” applies to backstory, as well. For example, if two characters have met before, you could tell the reader “Suzie had met Jim before,” or you could have Suzie say “Hey, Jim,” showing that they’ve met before.

Just a thought. 🙂

I can gree to that, especially after reading Dean Koontz’s latest suspense, 77 Shadow Street. For the most part, it did feel like he kept lagging because he seemed addicted to describing even the tiniest of details in any particular situation. A brief description in the alternate timeline here and there would’ve been okay, but he went on for page after page of descriptions, which ruined the suspenseful atmosphere for me. It had a couple nice moments, but constant showing simply did not do the story well. Talk about a struggle.

As of yet, I haven’t read anything from Stephen King aside from The Gunslinger and Carrie, though, from what all I’ve heard about his LARGE books, he knows how to push the story forward appropriately, in style and taste, and, most importantly, in pacing.

Maybe that’s why I’ve heard more people enjoy King over Koontz.

Though I can also see what I’ve been doing wrong in my own story, I thought there was a reason I couldn’t feel satisfied about it.

Going back to the James Scott Bell quote above… I would say that the show vs. tell balance is different between genres. To generalise, you can get away with more telling in a male-focused genre, but you need a lot more showing if your primary audience is female. JSB writes legal thrillers, so I would say that he can get away with more telling than, say, a romance author.

Thoughts?

That explains it! (Pun intended.) Now I understand why I can discern the difference between novels penned by men and women, generally speaking. I know I’ve read some fiction supposedly written from a man’s point of view, but unconvincingly due to feminine traits like focus on floral scents, texture of the cat’s fur, “frilly” stuff not common to farmers and blue-collar types. Yeah.

I have received this same feedback, and I am working to improve my own writing, not just to accent one over the other, but to do, as you suggest, what is right for the story. This includes both showing and telling. I think I’m just beginning to understand that a good story has these in the right proportion and in the right places.

Thanks Mike!