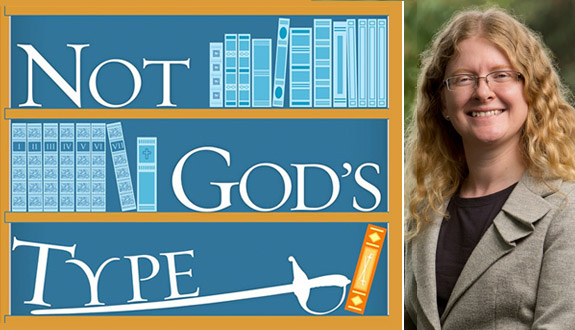

In his interview with professor and apologist Holly Ordway, Brandon Vogt asks about her conversion from atheism to Catholicism, as recounted in her latest book Not God’s Type: An Atheist Academic Lays Down Her Arms. Interestingly enough, it started with “Christian literature.”

In his interview with professor and apologist Holly Ordway, Brandon Vogt asks about her conversion from atheism to Catholicism, as recounted in her latest book Not God’s Type: An Atheist Academic Lays Down Her Arms. Interestingly enough, it started with “Christian literature.”

…classic Christian literature planted seeds in my imagination as a young girl, something I write about in more detail in my book. Later, Christian authors provided dissenting voices to the naturalistic narrative that I’d accepted—the only possible dissenting voice, since I wasn’t interested in reading anything that directly dealt with the subject of faith or Christianity, and thus wasn’t exposed to serious Christian thought.

I found that my favorite authors were men and women of deep Christian faith. C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien above all; and then the poets: Gerard Manley Hopkins, George Herbert, John Donne, and others. Their work was unsettling to my atheist convictions, in part because I couldn’t sort their poetry into neat ‘religious’ and ‘non-religious’ categories; their faith infused all their work, and the poems that most moved me, from Hopkins’ “The Windhover” to Donne’s Holy Sonnets, were explicitly Christian. I tried to view their faith as a something I could separate from the aesthetic power of their writing, but that kind of compartmentalization didn’t work well, especially not with a work of literature as rich and complex as The Lord of the Rings.

Eventually, I came to the conclusion that I needed to ask more questions. I needed to find out what a man like Donne meant when he talked about faith in God, because whatever he meant, it didn’t seem to be ‘blind faith, contrary to reason’.

The Christian writers did more than pique my interest as to the meaning of ‘faith’. Over the years, reading works like the Chronicles of Narnia, The Lord of the Rings, and Hopkins’ poetry had given me a glimpse of a different way of seeing the world. It was a vision of the world that was richly meaningful and beautiful, and that also made sense of both the joy and sorrow, the light and dark that I could see and experience. My atheist view of the world was, in comparison, narrow and flat; it could not explain why I was moved by beauty and cared about truth. The Christian claim might not be true, I thought to myself, but it had depth to it that was worth investigating. (bold, mine)

In this podcast, Ordway talks about the “inconsolable longing” that novels by Tolkien and Lewis evoked in her. Even though their stories were not explicitly “Christian,” it was their perspective, their worldview, that “planted seeds” in her imagination and drove her to find out more about the authors. In fact, it was this research which led her to discover the religious beliefs of the authors and the stories’ Christian underpinnings. At first, Ordway felt somehow tricked. The sense of hope, transcendence, and beauty evoked by these novels was an outgrowth of the beliefs of their authors. Yet this reality is what eventually initiated her journey to Christianity.

There is a belief among many evangelical authors that fiction can only be “Christian” insofar as Christian elements and themes are explicit. I think Ms. Ordway’s testimony challenges that assumption.

There is, without question, different views as to the aim of Christian fiction. On one side are those who believe Christian fiction should target Christians — encourage them, inspire them, reinforce their values, and ultimately make them better believers. On the other side are those who believe Christian authors should target seekers — whet their spiritual appetite, disarm antagonism, simplify biblical themes, reinforce a biblical worldview, and leave them thinking about God, Christ, sin, and/or heaven and hell. Or simply pique their interest in the author and where she is coming from.

However, for the most part, writers and publishers of Christian fiction aim at the Church, not the world. This is a fatal error. The downside of such an approach is that, though well-intentioned, writing and marketing novels exclusively to Christians limits the degree to which authors can “plant seeds” in the imaginations of seekers. Ordway’s testimony is a reminder that simple worldview elements can stoke a reader’s spiritual quest.

Interestingly enough, many question whether or not novels like The Lord of the Rings trilogy should even be considered “Christian.” In Ordway’s case, it was “Christian enough” to prompt her to begin a quest — a quest to research the author. She came to the conclusion that she “needed to ask questions” about why men like Donne, Lewis, and Tolkien all shared this same worldview.

Their poems and novels led her to investigate the authors and their faith.

And this is where I believe many Christian fiction defenders err. The best apologetic for a specific worldview is not the story, but the author. This isn’t to say that our stories should not contain Light. Rather, theological specificity should not be sought in fictional tales. In fact, the more we demand a doctrinal checklist from one’s novels, the further we move from telling stories to preaching sermons. Ultimately, the best apologetic is the author, not the story. If people want to know what an author believes they should ask them, listen to them, research them. But demanding theological specificity from fiction eliminates the author’s ability to “plant seeds in the imagination” and the reader’s desire to, as Ms. Ordway did, “ask more questions.”

She will also have found that CS Lewis was an equally reluctant convert to Christianity.

Thanks for this, Mike. It’s brilliant.

Great article, Mike, and thanks for the link to the interview. It’s very encouraging and confirming to those of us who are Christian authors writing for a general audience, and I couldn’t agree more with your points here. It also provides a nice parallel to the interview I did with author/artist Stephen McCranie on Speculative Faith a few weeks ago, in which we touched on some of the same ideas from a slightly different angle.

Great article Mike – couldn’t agree more. Hoping my fiction will engage the general population for just those reasons.

-Mike, your last paragraph says it all. We seek to plant those seeds in the imagination of our readers. I just wish the publishers believed as we do. Tolkien would never have been published by today’s Christian booksellers. “What, a fantasy with sorcerers and monsters?” But please, let’s have yet another made-up story about the Amish.

Thanks for this wonderful article Mike, and thanks for attaching the interview. I too love to read the works of C.S. Lewis, and it’s interesting to compare some earlier works with later one’s. Time to re-read Narnia I think.

Thanks for this, Mike. What a blessing to read this testimony. And this is my hope and dream exactly–that my work will touch seekers, will plant those seeds and questions in their minds. And that, ultimately, they will find the Answer.