Epic love stories are not my genre of choice, which is what made Atonement such a pleasant surprise.  That’s not to say the film isn’t “epic” or that it’s not a “love story,” but that, in the end, it’s aiming for something altogether different. Some have criticized the movie on the grounds of this atypicality — in other words, the expectation of a more sweeping romance. For me, it was precisely this element that took the film from being a “date movie” to a deeply moving — even disturbing — contemplation on the repercussions of choice, the need for forgiveness, and the nature of fiction.

That’s not to say the film isn’t “epic” or that it’s not a “love story,” but that, in the end, it’s aiming for something altogether different. Some have criticized the movie on the grounds of this atypicality — in other words, the expectation of a more sweeping romance. For me, it was precisely this element that took the film from being a “date movie” to a deeply moving — even disturbing — contemplation on the repercussions of choice, the need for forgiveness, and the nature of fiction.

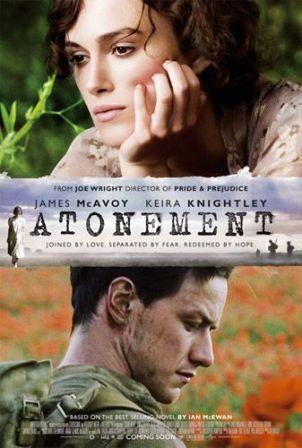

Joe Wright’s adaptation of the acclaimed novel by Ian McEwan opens with a musical theme that will propel the movie to its shocking conclusion — the pounding of typewriter keys on paper. Woven into the very score, the sound becomes an ominous metronome punching out the tale, an omniscient reminder of the authors that play a part in its unfolding. At the story’s center is 13-year-old Briony Tallis (played chillingly by Saoirse Ronan) on her family’s estate. An aspiring young playwright, she inadvertently witnesses a mysterious encounter between her sister Cecilia (Keira Knightley) and Robbie Turner (James McAvoy), the son of the family’s housekeeper. Briony is confused and eventually angered by what she thinks she sees. That chance encounter sets in motion a chain of events that ultimately leads to Briony accusing Robbie of a crime he didn’t commit.

All three lives spiral into disorder from there, and the film follows them as they seek to regather the strands and survive the repercussions of Briony’s accusation. In her case, it is about atonement — absolving herself of the guilt of her foolish choice and making amends to those she’s destroyed. But, we discover, the consequences may be far greater than she ever imagined.

Author Ian McEwan, was recently interviewed by the New York Times Magazine’s, Deborah Solomon, and asked about this theme of “atonement” in the book and the movie:

Solomon: It seems to me that the impulse to atone is a religious one, and yet you are a self-declared atheist.

McEwan: Yes, I am an atheist, and probably Briony is, too. Atheists have as much conscience, possibly more, than people with deep religious conviction, and they still have the same problem of how they reconcile themselves to a bad deed in the past. It’s a little easier if you’ve got a god to forgive you.

Aside from the jab about atheists possibly having “more” conscience than religious folk, I find the author’s perspective fascinating. This idea of how we “reconcile [our]selves to a bad deed in the past” is central to Atonement. And, in a way, how the film answers that may be more indicative of the essential difference between people who’ve “got a god to forgive [them]” and those who don’t.

A clever storytelling device is employed early on that plays a key role in the story’s unfolding revelations wherein the audience is made privy to an event from two different perspectives. Throughout the film, our sense of reality is undermined — what is fact and what is fiction — a dynamic which proves pivotal to this tale. To say more would be to tip the director’s hand.

A clever storytelling device is employed early on that plays a key role in the story’s unfolding revelations wherein the audience is made privy to an event from two different perspectives. Throughout the film, our sense of reality is undermined — what is fact and what is fiction — a dynamic which proves pivotal to this tale. To say more would be to tip the director’s hand.

From scenes of idyllic English gardens to vast battlefields in disarray, there is a real cinematic breadth to this movie. One scene, in particular, is worth noting: A long tracking shot — a single, unbroken scene — which follows Robbie, injured and weak, as he walks down the beach at Dunkirk surveying the carnage and chaos, soldiers dying and some at play, a men’s choir singing a hymn under a gazebo, into a saloon where soldiers are drinking and spouting military propaganda, and then to a theater where a grainy black and white film reveals lovers kissing, where he stops to weep about what could have been. It’s a terrific sequence.

But, in the end, it’s not the scope of the cinematography but the breadth of story, the complexity and depth, that make this a really good movie. Can we rewrite the script of our lives? Can we replace tragedy with a happy ending? Can we ultimately atone for foolish, childish choices? And can the very nature of reality be altered by one’s perspective? As I’ve reflected on Atonement, I’ve found myself pondering some of these questions. It’s definitely one of the better movies of 2007.

Hi Mike, only read the title. Going to skip this because I’m going to read the novel and then watch the movie. And THEN I’ll come back and read your review:)

I initially skipped it, too, because I had scheduled a Monday trip to see it, but it got postponed until today.

So, thank you for the background. I prefer to see films “cold turkey”, knowing that if I haven’t read the book but want to see the movie, no point to read the book first. And I might read only a partial review–much like a sentence or two of backcover copy for a novel. I want to know just enough to decide it I plan to see/read it without having anything “spoiled”.

This is a haunting film for sure. Those things that make you uncertain permeate it until the final scene. Then you understand what is amiss.

Good review. I’ll probably review it on my blog, too, but not completely sure yet.

Sounds like my type of movie!

(I’ll post my review on Monday, Mike, if you care to read it.)