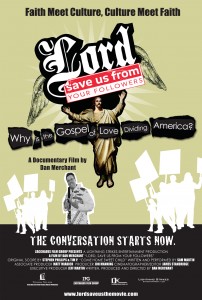

I was recently privileged to preview Lord Save Us From Your Followers, a provocative new documentary from Dan Merchant (his book of the same  title was published by Thomas Nelson). Subtitled “Why is the Gospel of Love Dividing America?” the film takes a hard, but pretty fair, look at the state of evangelicalism in the States and the tone of conversation between professing Christians and the culture.

title was published by Thomas Nelson). Subtitled “Why is the Gospel of Love Dividing America?” the film takes a hard, but pretty fair, look at the state of evangelicalism in the States and the tone of conversation between professing Christians and the culture.

Merchant is a likable guy. He is humble and funny, traveling the country (wearing a jumpsuit covered with religious-themed bumper-stickers), befriending transvestites and gays, interviewing politicians and pundits, asking the question: “Why is the gospel of love dividing America?” Merchant disarms the typical incivility of such encounters, which leads to some genuinely touching moments.

Lord Save Us from Your Followers is part of the growing movement of young American evangelical Christians who are distancing themselves from the excesses of organized religion, calling for a return to Christianity’s true meaning, and initiating a more open-ended, diplomatic, affable tone to cultural engagement. Some have labeled this approach as neo-apologetic and this, they assert, builds the bridges that our rhetorical rancor have burned.

As I’ve said before, I’m a bit suspicious of this trend to criticize Christianity — not because I think that Christians aren’t screwed up or that American evangelicals aren’t often a parody of the real thing — but because the neo-apologists tend to two extremes. One, they focus on the worst elements of the Church and ignore the good. And Two, they tend to compromise Absolutes (i.e. Scripture) along the way. It wasn’t until the closing segments of Lord Save Us from Your Followers that these elements converged, leaving me fairly disturbed.

In the hugely popular book Blue Like Jazz by Donald Miller, the author tells a fascinating story about how a handful of Christians at uber-liberal Reed College set up a “Confession Booth” during a week of campus pagan partying and excess. The booth, however, wasn’t for students to confess their sins, but for Christians to repent to the Reed students. Donned as monks, Miller and company asked Reed students for forgiveness regarding their lack of love and Christ-likeness.

Spinning off of this story, Merchant erects a “Confession Booth” at Portland’s Gay Pride celebration. As homosexuals reluctantly enter the Booth, Merchant apologizes for the Church’s treatment of gays throughout history, as well as his own attitude toward homosexuality. The sincere reaction of those who entered his booth was both captivating and disturbing.

It left me with oodles of questions. For one, do post-modern Christians still believe that homosexuality is a sin? If they don’t, then how do they handle the numerous Scriptural warnings and prohibitions against same-sex relationships? On the other hand, if homosexuality IS a sin, how and when do Christians actually say that without appearing condemning? More often than not, any opposition to homosexuality is viewed as anti-Christian. So it’s a lose-lose situation for the evangelical Christian — even a cordial, compassionate one! Furthermore, by confessing our sins to gays, aren’t we in danger of condoning a lifestyle that is both destructive and completely out of whack with God’s wishes?

Probably more specific to my unease with the film’s message was the concept of confessing our sins — or the sins of the Church — to non-Christians. Yes, we need to approach the lost, not with a sense of superiority and condemnation, but with gentleness and mercy. Frankly, less finger-pointing and fire-and-brimstone would be refreshing. But evangelism by apology seems fraught with danger. Yes, our conduct and character are intrinsic to our message. But the truth is, no “messenger” ever perfectly embodies their “message.” Christians will always have something to apologize for because they aren’t perfect. So where do we stop?

And what happens after we apologize? Do we then begin to tip-toe into a presentation of the Gospel, holding our breath lest we offend those who’ve (hopefully) absolved us? At some point, even the “apologetic” Christian will have to stand for something — and just like Jesus, that “something” just might rankle and infuriate others. Besides, who said the Church should be loved by everyone? Last I checked, Jesus promised His followers that they would be, um, rather hated:

“If the world hates you, keep in mind that it hated me first. If you belonged to the world, it would love you as its own. As it is, you do not belong to the world, but I have chosen you out of the world. That is why the world hates you. Remember the words I spoke to you: ‘No servant is greater than his master.’ If they persecuted me, they will persecute you also. (John 15:18-20 NIV)

In light of this, maybe we should be more thankful for the cultural “persecution” and less worried about our PR image.

Yes, films like Lord Save Us from Your Followers remind us about our need to look in the mirror, identify the disconnect, and be more humble, gracious, and Christlike in our approach. But at some point, this conversation has to shift away from how screwed up Christians are to how merciful and powerful the Lord Jesus Christ is. There will always be bigots, buffoons, legalists, and hypocrites in the Church. But God has shown, throughout history, that the Gospel can survive just fine without my apology.

I think Donita Paul's Dragonkeeper books say it perfectly. It's either DragonKnight or DragonLight (I think the latter) in which some men have been going around in the robes of Paladin's (who is not Jesus, but the church) servants and mistreating and conning people. Thus, when the main characters, who are Paladin's servants, come through, the townspeople are afraid and distrustful of them. At length, the male lead asks a townsman whose trust he's trying to earn the following:

"Suppose a man were to steal your clothes and rob your neighbor, then return your clothes to you and frame you for the theft. Does it make you guilty simply because your clothes were present?" (That's a paraphrase; he said it better.)

At any rate, his whole point is that just because those men looked like they were from Paladin didn't mean they were, and it didn't mean the actual servants of Paladin were in any need of apology, because they weren't guilty of it.

And while I am aware of places in Scripture where people prayed, on behalf of the nation, for forgiveness of particular sins, that was in intercession and prayed to God, not men. I think that's a huge distinction.

Excellent points, Mike. Good conclusion.

Mike, I've been hearing a lot about this film. Seems a solid piece of work. And your questions are thought-provoking. I don't know how Christians should deal with their problematic cultural image–the polar opposite from Jesus' image, apparently. A collective apology seems a good start. But it does need to be followed up. Could that pave the way for Jesus to come perform a miracle? That seems more organic ("holistic") to me than being planter, waterer, and harvester all at once. Relationship must begin with mutual respect and understanding–and that can't happen without an understanding of respect. If an apology furnishes that, I would hope in time there may be greater openness to authentic hearing rather than knee-jerk reacting.

Appreciate your thoughts.

Hey, Mick! Thanks for visiting. I agree with Merchant and others about the tone of conversation needing to change. We won't "win" anyone over with a shrill, condemning, posture. But while an apology might furnish "mutual respect and understanding," I'm wondering where we go after that. At some point, Christians must be about sharing the Gospel. And the Gospel is a "stumbling block" to some. Of course, sharing the Gospel should occur relationally, rather than didactically. Yet no amount of apologies can lesson the reality that some will still see us as divisive, angry, judgmental, and unloving, no matter how much we apologize.

My fear is that this approach is a retreat from the Gospel, rather than a furtherance of it. Absolutely the Church needs to check herself. But if our goal is simply to be more respected, we inevitably are forced to nix certain crucial elements of the Gospel. Thanks again for your comments, Mick!

I don't believe that our Lord even has a polar opposite. The Pharisees aren't opposite of him, for he he had Pharisees for followers (and showed them love and compassion as well as the more famous and frequent condemnations). The tax collecters, fallen women and other overt sinners aren't opposite of him, for he ate with them and taught them.

Apologizing for Christianity is a well-meaning, ill-fated message, and most importantly, steals joy.

As a recovering anti-Christian who would have, in a former life, allied himself deeply with homosexuals, atheists, outcasts, contrarians, and the cultural mainstream, I would have gladly accepted the cowtowing apologies of Christians for their so-called Lord. It would have comfortably confirmed my deepest suspicions: that they are weak-minded and blind.

The culture against Christians calls us, collectively: bullies, hypocrites, powerful and oppressive, but not because they believe us to be. We shouldn't play in the reigning culture's web of doublespeak at the expense of the Gospel.

xpaul, your reference to "doublespeak" reminded me of something else I thought of as I read Mike's excellent article—a part of our culture opposed to revealed truth from God is changing language to fit their ends. Thus, "homophobic" now means opposed to homosexuality, "marriage" means a committed relationship between two people regardless of sexual orientation. And "Christian" apparently means conservative right-wing political advocate shouting hateful slogans in rallies.

But the thing I really wanted to comment on is this. The people who think Christians confessing our sins to non-Christians is a good way to begin a conversation about the love gospel are missing the heart of Christ's work—redemption. It's not about our works.

The confession idea seems to me to give the message that I should do a little better because I, and others within the church, have fallen short, or gone off track, or headed in the wrong direction.

Well, yes, I have … we have. Which is why we need a Savior, why we need the gift of grace.

My confessing to non-Christians seems like a modern day animal sacrifice, which can give the false idea that what I need to qualify as a Christian is just a little more love in my heart. (For the Jews it would have been, just a little more blood on the ground).

The point is this: gays or bank robbers or slanderers or drug dealers or complainers or corrupt politicians or prostitutes or gossips are not headed to hell because of what we do; it is our rejection of Jesus Christ, or our acceptance of His sacrifice on our behalf that determines our eternal destiny.

In that regard, we need more fire-and-brimstone preaching, I think, not less. But today's fire-and-brimstone message seems to be, Stop doing what you're doing so you won't go to hell. What I see in the pages of Scripture instead is, Come to Christ all you who are exhausted and overburdened and He'll give you … rest, forgiveness, freedom from guilt and the law and sin and death, the hope of heaven, a place in His family. And for those who reject Christ? None of the above.

John 3:18 says it best "… he who does not believe has been judged already, because he has not believed in the name of the only begotten Son of God."

Like any relationship, my Father-child connection with God makes a difference in my life here and now, either as I obey Him or as He disciplines me. And of course that spills out in my relationships with everyone else, either in my obedience of what God would have me do or my disobedience. So I'm not saying Christians should have no regard for others. Actually just the opposite.

But it has a different motive. Because I have regard for God and His dictates, then I have regard for the people He puts in my life—sometimes to speak the truth in love … which can be divisive.

Rebecca, thanks for supplying the missing piece. I believe you are right.

I've always liked that Jesus didn't pussyfoot around the issues …He simply said, "Neither do I condemn you …" followed by what we seem to so easily forget … or avoid … "Go and sin no more." Of course, then you have to call sin, sin. Lots of people not real comfortable with that concept anymore. And I'm not proof positive of this, but right off hand I can't think of anyone He apologized to. Just some simple thoughts …