Rohullah Nikpai‘s appearance at the 2012 London Olympics is a reminder of just how important nationalism can be. In the 2008 Olympics, Nikpai, of Afghanistan, won a bronze medal in taekwondo. It was a truly historic moment. Why? Because it was the first  Olympic medal ever won by his country. Now Nikpai returns bringing higher hopes for himself and greater respect for the nation he represents. It’s probably why some of the most poignant moments at the Olympics happen during the medal ceremonies. Seeing a country’s flag unfurl, their national anthem played in celebration of its athletes’ achievements, can be truly inspirational.

Olympic medal ever won by his country. Now Nikpai returns bringing higher hopes for himself and greater respect for the nation he represents. It’s probably why some of the most poignant moments at the Olympics happen during the medal ceremonies. Seeing a country’s flag unfurl, their national anthem played in celebration of its athletes’ achievements, can be truly inspirational.

Of course, not everyone is happy about these patriotic celebrations.

Much has been made of the evils of nationalism. Erich Fromm, the humanist / social psychologist, once said, “Nationalism is our form of incest, is our idolatry, is our insanity. ‘Patriotism’ is its cult.” Likewise, many secularists and political leftists see nationalism as the driving force behind war, secession, and genocide, the cause of many of the world’s ills. It’s why many believe we should move toward a “global community,” a one world government where “citizens of the world” unite under one banner, not hundreds. Or as John Lennon sang,

Imagine there’s no countries

It isn’t hard to do

Nothing to kill or die for

And no religion too

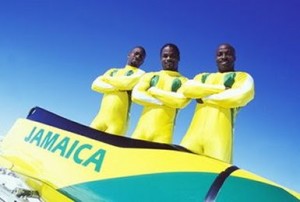

John Lennon Imagined a world with no Olympics. Which doesn’t  sound very fun. I mean, in “shared societies” everyone wins. So in John Lennon’s Olympics we could have never enjoyed the Jamaican Bobsled team. Or Rohullah Nikpai’s bronze medal.

sound very fun. I mean, in “shared societies” everyone wins. So in John Lennon’s Olympics we could have never enjoyed the Jamaican Bobsled team. Or Rohullah Nikpai’s bronze medal.

In many ways, the Olympics grate against some of our most sacred ideologies. Perhaps the most obvious is multiculturalism. Multiculturalism celebrates racial, ethnic, cultural diversity. But to appreciate different cultures — food, religion, customs, history — requires the amplification of national distinctives; it implies nationalism. So multiculturalism, which is one of the planks of secular ideologists, creates a dilemma for the opponents of nationalism. Either we celebrate the fact that Afghanistan won its first bronze medal, or we don’t. If we respect this athlete’s achievements, and all it means for his country, then we concede to a certain degree of nationalistic pride.

It’s one thing to perpetuate myopic self-interest and antagonism for “lesser” nations. But a healthy nationalistic pride should cause us to applaud, rather than scorn, the struggles and successes of other nations. This diversity, competition and camaraderie is what makes the Olympics, and the human race, so special. However, it also means some nations will be better than others. And, in the end, this may be the real reason people oppose nationalism.

But the real problem with John Lennon’s Olympics is, It isn’t worth fighting for. “Nothing to kill or die for,” he sang. And is anything that’s not worth dying for, worth living for? Of course, that can be twisted to hideous extremes. But so can the idea of a “shared state.”

Apparently, God Himself appreciates a degree of nationalism. In heaven “a great multitude that no one could count, from every nation, tribe, people and language” (Rev. 7:9) is present. Jamaicans. Afghans. Brits. Aussies. Every banner under One Banner; many anthems under One.

Nationalism isn’t erased in heaven, it’s celebrated.

Your last thought on nationalism and John Lennon and the line “Nothing worth killing for, nothing worth dying for” is why I hate the song. I couldn’t see if there was anything dying for, then nothing is worth living for.

I didn’t know there was a Jamaican bobsleigh team.

And you’re right, no Olympics doesn’t sound like a fun world.

We live in times where young people are conditioned to die for their country or religion. The utopy of world peace is further away than ever. Anders Breivik, the terrorists of 9/11 they want to kill and want to die. It is not John Lennon who rules, but Charles Manson. Paranoia is in us all.