I recently re-watched a film I’d loved as a kid only to be shocked at how bad it was. What had I been thinking? Well, I was thinking like a kid back then. Now, I’m thinking like an adult. So which perspective on the film was the right one — the kid who was totally, blindly, immersed in the movie or the adult whose aesthetic tastes have been refined?

Sadly, the adult in me won out. Which left me yearning for the eyes of a child.

Nowadays, anyone can be a critic — kid or adult. On our recent vacation (in which we sampled multiple eateries), my wife was so enthused about one specific restaurant that she vowed to return to the hotel and write a review. True to her word, she proudly posted her first ever restaurant review. From my perspective, both the review and her giddiness were rather childish. In a good way.

So I’m thinking we review too much like adults nowadays. It’s the downside of democracy. Everyone’s afforded an opinion. And, my, how seriously we take our opinions.

C.S. Lewis addresses this balance between art critique and art appreciation in his Experiment in Criticism. Lewis suggests that being a critic of books is actually a hindrance to good reading. Or to put it another way, being  too adult keeps us from enjoying many a good book. He writes:

too adult keeps us from enjoying many a good book. He writes:

I doubt whether criticism is a proper exercise for boys and girls. A clever schoolboy’s natural reaction to his reading is expressed by parody or imitation. The necessary ingredient for all good reading is to get ourselves out of the way. We do not help young people by forcing them to keep expressing their opinions. Especially poisonous is the kind of teaching that encourages them to approach every literary work with suspicion. It springs from a very reasonable motive in a world full of sophistry and propaganda we want to protect the rising generation from being deceived, we want to forearm them against false sentiment and muddled thinking. Unfortunately, the very same habit that makes them impervious to the bad writing makes them impervious to the good. (emphasis mine)

This idea that the prerequisite “for all good reading is to get ourselves out of the way,” seems crucial to art appreciation and, subsequently, a good review. There’s a sense in which we must submit to the story before we can rightly critique it; we must approach a piece first, not as a judge, but as an open-minded observer. A child, if you would. In fact, Lewis suggests that the worse thing we can do to a young reader is to force them to “keep expressing their opinions.” He describes this as “especially poisonous.”

Of course, this grates against many current academic trends. For instance, deconstructionism, as it concerns literary criticism, asserts that before we can fully interpret a piece we must recognize certain preconceptions, understand the author’s “filter.” We can’t “get” Huck Finn until we understand Twain’s culture and politics. We can’t appreciate The Lord of the Rings until we grasp Tolkien’s Catholicism and his experience in the British Army. Yet, while understanding an author’s worldview and cultural milieu may illuminate aspects of her story, that approach ultimately militates against Lewis’ concept of submitting to the story. In other words, we must become more adult in order to “get” the story. This, according to Lewis, is poisonous.

But there’s another problem. Understanding the “rules” or nuances of a given medium are essential to appreciating that medium. It’s as we understand language and grammar, pacing and character development, that we can best appreciate a story. Studying musical theory can make one value the great composers. Learning about cinematography and camera work has not detracted from my love of film. In fact, it’s made it grow. But does this too fly in the face of Lewis’ assertion?

Perhaps, as Lewis says, we should not approach art, first, as a critic. Children need to read Narnia without the baggage of their parents’ “interpretations.” Nevertheless, weighing those interpretations and appreciating the critical elements of art, can be a crucial element to its enjoyment. All of which makes me wonder — Does art critique have to be an obstacle to art enjoyment?

Either way, it’s still a dance between seeing through the eyes of a child or an adult. In some ways, it’s impossible to rightly critique a piece without surrendering to it. Being overly critical can keep us from appreciating a film or book. But being un-critical makes us gullible to all kinds of propaganda, and leads to the proliferation of mediocrity. And bad movies.

Reviewing like a kid means putting aside the critical elements — not ignoring them, just getting them out of the way long enough to resist “suspicion.”

Still, the more our “review culture” encourages people to “keep expressing their opinions,” there will be no shortage of reviewers who are too big for their britches.

Several thoughts, here:

“The necessary ingredient for all good reading is to get ourselves out of the way. We do not help young people by forcing them to keep expressing their opinions. “

You’ve just nailed my central conflict as a reading addict…and a high school English teacher. Because being one doesn’t necessarily help the other. I can say, without a doubt, that if it were left up to me, I’d force a lot less criticism out of my students, especially my freshmen. Honors and AP (advance placement), that’s a little different. They’ve signed up for those classes with the intent of pursuing criticism, that’s the whole point of the class. However, leading them into a thoughtful critique without destroying the “magic” is a tough, tough balance.

I’ve swung through entire swathes of the spectrum. I grew up reading like a kid: reading EVERYTHING. For a long time, I probably read what some would consider the lowest common denominator: I was obsessed with all the Star Wars and Star Trek novels, and at one time, could say I owned every one. I eventually grew out of those, and while they occupy proud places on my shelf because of their role in my development, I can’t see myself actually reading new SW or ST novels.

With horror, I started with Stephen King and Dean Koontz. I widened my perspective, really scoping out a lot of different, maybe even “literary” horror writers, but recently decided to start reviewing mass market horror again, because I was afraid I was getting too elitist.

So now, I’ve swung back to the point of reading just about everything. Probably the only thing I’m a critic of is technical craft. If the prose is too clumsy and unreadable, the dialogue stiff, I can’t read it. It’s gotta be well written.

But movies?

I am a kid, and will always be a kid. I also refuse to bow and get myself a big flat screen with surround-sound, so I don’t have to go the theaters anymore. When it comes to movies, I want, in this order, on the big-screen: action, fun, special effects, laughs, action, explosions, kung fu, jump scares, more action, and nachos and cheese with jalapenos (did I mention action?). If there’s good storytelling along the way, that’s a bonus.

“Reviewing like a kid means putting aside the critical elements — not ignoring them, just getting them out of the way long enough to resist ‘suspicion.’ ”

Well said, Mike. While I’m all for reading insightful reviews, sometimes I don’t bother with Amazon or Goodreads because it seems most people just get too picky. I look for an interesting plot or character, something that screams “Hey, that’s a brand new idea” or at least a new take on an old genre.

Incidentally, this is one of the reasons I try not to police my boys’ choices of reading (because I know parents who do.) Their enjoyment of a new book is something that inspires me.

Huh.

I’ve often thought, and still believe, that a review is nothing more/less than a window into the soul of the reviewer. No ink blots required…any piece of art will serve as a dandy projective test that tells you far more about the reviewer than the work.

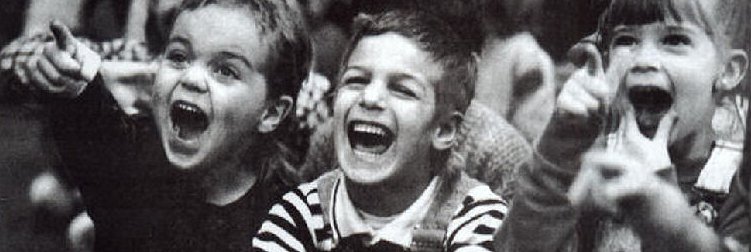

Absolutely, the average young person (such as those in the photo atop your post) is simply focused on emotion… does this make me *feel* good? Cognitive appraisal doesn’t reach its potential until much later (I still remember loving the stories in the “Dick & Jane” readers of kindergarten. Now, the term “Dick & Jane-level writing” is a perjorative.)

So the “you” of your childhood was right… and the “you” of today is right, though the two of you are measuring by quite different yardsticks. The film didn’t change. You did.

Interesting post, Mike. And I think you’re on to something. If we’re too critical of anything were apt not to enjoy it. Another review thing that’s happening now involves reviewers bashing anything that doesn’t fit the genre or style they happen to like. I don’t particularly care for romance, but I know good writing when I see it and if the book happens to be a romance, I try to look past that.

I actually have separate modes when I read. Sometimes I have on my “writer/critic” hat, other times I leave it off to just enjoy the work for itself. I generally prefer to read WITHOUT the critic hat on, but if a book gets itself in my way I’ll default to that as a way to figure out why I didn’t enjoy the book more.

That’s also why I don’t have a strictly book blog. I want my reading experience to be as organic as possible. I also don’t write up reviews for every book I read.

Applying this to earlier discussions, this is one reason I read very little Christian fiction. I feel like I have to always be watching doctrine.

I like this post a lot. It made me think of The Avengers. Thinking back on the movie, I could have found a lot to criticize as an adult–plot holes, motivations that were not well-explained, character development was left to the previous films, etc.

But the movie was sheer Hollywood dazzle and entertainment, and I found myself ignoring the inner critic and just having a blast with it. It’s ok to have fun.