I used to be a fan of David Lynch. And then his films got weird. It could be argued they were always weird (see: Eraserhead). On occasion, he would mix in a traditionally linear narrative like The Elephant Man or The Straight Story. But his films have drifted more and more into absurdism.

I used to be a fan of David Lynch. And then his films got weird. It could be argued they were always weird (see: Eraserhead). On occasion, he would mix in a traditionally linear narrative like The Elephant Man or The Straight Story. But his films have drifted more and more into absurdism.

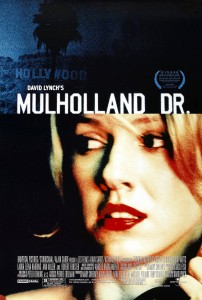

A friend recently mentioned Mulholland Drive (2001), for which Lynch was an Academy Awards Best Director Nominee. Coincidentally, Mulholland Drive was the last David Lynch film I watched.

This person shared my bewilderment with the film. They said:

I was confused. Perplexed. Disturbed. Does that mean it was good?

If you haven’t seen the movie, it is everything this person described it as — confusing, perplexing, and disturbing. (And be forewarned, there is a very graphic sex scene in this film.) It contains Lynch’s signature stylistic surrealism. But, boy, it’s a head-scratcher.

So does that mean it was good?

Carina Chocano, former staff writer for the LA Times, in her review of Lynch’s follow-up film, Inland Empire, confirmed my suspicions about Lynch’s descent into celluloid gibberish:

. . .clocking in at one merciful minute under three hours, Lynch’s much-anticipated follow-up to “Mulholland Drive” signals a hale swan-dive off the deep end, away from any pretense of narrative logic and into the purer realm of unconscious free association. . .

Lynch has talked about the freedom afforded him by video-shooting 40-minute takes, writing scenes moments before they are shot, following ideas into places they couldn’t have gone had complicated lighting set-ups been required. But the lack of structure and rigor doesn’t seem to serve him here, and the film, which begins promisingly, disappears down so many rabbit holes (one of them involving actual rabbits) that eventually it just disappears for good.

There’s a fine line between ambiguity and incoherence. Lynch appears to have crossed that line, taking a “a hale swan-dive off the deep end,” and moving from the ingenious to the incomprehensible.

But is that “line” so easy to discern anymore? And is crossing the line into absurdism even bad?

Absurdism seems to be a commodity we are more willing to tolerate these days. Some literary novels are little more than stylistic navel gazing. Then there’s films like Terrence Mallick’s meandering Tree of Life, which one critic described as “Less Plato than metaphysical Play-Doh.” Tarantino’s latest film Django Unchained has been described as an “incoherent three-hour bloodbath.” Apparently the blood makes the incoherence tolerable. Nevertheless, today’s audiences seem to tolerate nonsense and incoherence like never before. We no longer need stories to “make sense.” In fact, NOT making sense may be the purpose of the piece.

In fact, there are techniques to producing literary mumbo jumbo. Writer LA Quill provides these popular techniques for writing “literary nonsense”:

- cause and effect that doesn’t make any real sense

- portmanteau (combining words together to form new words that often don’t make any sense at all unless you know the root words)

- neologism (making up words, sometimes by the dozens)

- imprecision or deliberate vagueness

- simultaneity

- arbitrariness

- infinite repetition (which isn’t as annoying as you might think when done correctly)

- nonsense tautology

- reduplication

- absurd precision

Thankfully, these “techniques” were not utilized in the author’s explanation. She employed a proper use of sentence structure, grammar, and punctuation to disassemble the pieces. Which, as I see it, is a flaw of artistic absurdism:

Absurdism requires logic and order to make its point.

Pollock’s paintings, after all, are framed. I heard one man describe his tour of some “postmodern architecture.” The structure contained doors on the ceiling, columns that ended midway in the air, and stairways that disappeared into empty walls. The tour guide gushed about the structure. The man asked the tour guide, “So, is the foundation stable?” Point being, postmodern buildings are built on modern foundations.

David Byrne, frontman for Talking Heads, employed nonsensical techniques in songwriting. From Wikipedia: “Byrne often combined coherent yet unrelated phrases to make up nonsensical lyrics in songs.” It was the basis for the film Stop Making Sense, which, thankfully employed very traditional, orderly musical elements. In other words, Byrne sang on key while singing about hooey.

But besides the fact that nonsense requires sense to define itself, it appeals to us under the pretense of being “deep.” Sure, a great test of any art — whether film, music, book, or watercolor — is if it stands up under multiple viewings. Does it make us think, draw us back into its world? Yet there’s a danger in assuming that ambiguity equals profundity, that obscurity is artsy, that the more cultured a film is, the more brow-scrunching and head-scratching it will provoke. “I don’t know what it meant,” says the critic, stroking his goatee. “But, man, it was deep.” It’s the artistic version of the Eastern riddle, “What’s the sound of one hand clapping?” The question poses as profundity when, in reality, it is nonsense. Likewise, ambiguity that results from meaninglessness is not profound, it is simply unanswerable.

So, what makes absurdism “good”?

Perhaps it’s a line we individually have to draw. I’m not sure. Ambiguity can be an important literary tool. But there’s a huge difference between being vague, cryptic, and shifty, and being intentionally nonsensical. The more we celebrate blather, the more artists we encourage to take “a hale swan-dive off the deep end.” The New York art critic who finds sublimity in a feces-splattered canvas does little more than encourage more shit.

Truth is, it stinks, and we’d be better off just saying so.

So if you ask me, absurdism is only “good” as it draws us back to something meaningful. But, then again, doesn’t that undermine its very foundation?

I stopped listening to Tori Amos a long time ago because of this. Her lyrics stopped making any kind of sense. Listening was a unecessary and uncomfortable journey into her nonsensical mind, and quite frankly what I saw in there gave me the heebee geebees.

Pollock didn’t use frames. He used composition and color, neither of which is absurd. I hesitate to comment on this because I tend to be obscure unintentionally, and I often wonder why others don’t get my jokes or my stories. Just because others don’t understand my logic doesn’t mean it doesn’t exist. That’s the problem with artists/creators/writers, etc. If they understood the world in the same way that others did, they wouldn’t be artists.

“[Pollock] used composition ans color, neither of which is absurd.”

This is exactly my point, Jill. He uses something very non-abstract to create abstraction.

“Just because others don’t understand my logic doesn’t mean it doesn’t exist.”

Of course. But this assumes it’s “understandable,” not nonsensical. It’s one thing for your “logic” to be deep. It’s another for it to be absurd. There’s a big difference between being misunderstood because you’re profound and being misunderstood because you’re utterly mad.

Yes, what Mike said about being profound vs. mad. I know nothing of Pollock, so no comment on that, but I do know you, Jill, and if you are misunderstood it’s because you see things differently and have a quirky sense of humor, and some people get you and some don’t.

Example to illustrate. I visited a museum a while back. One piece of art looked like a picture of someone’s hair clippings. Well it was, but it was a *drawing* of hair clippings. It’s something that takes real, concrete skill–that “foundation” mentioned in the quote Mike used. Yet it used that skill in a very unconventional way. That’s cool. However, another piece was a giant painting of colored stripes. It looked like a bed sheet pattern. No, that’s not profound. It’s stripes. I don’t care what the colors represent to the artist or whatever–it’s stripes. Any house painter in the world could have done the same thing with a ruler and some masking tape.

About the stripes–it isn’t profound unless you view color and the regularity of shapes as profound. The stripes painting (I know what painting you’re talking about) does have a foundation of what makes art art; however, it doesn’t represent great skill. It’s a study, in my opinion, and it actually isn’t obscure in the least. It’s quite the opposite, very accessible, like bedsheets or curtains. It’s reductionists in spirit. Many artists who are obscure, intentionally or otherwise, are attempting to confront complexity and/or chaos. Essentially, I get what you and Mike are saying. Some artists don’t even want their art to make sense. Nonsensical art can be fun (as with Lewis Carroll), but it can also leave no way for the average person to enter in and take part in. It can be purposefully exclusive.

Purposefully exclusive–yes. That’s a good way to phrase it. And that’s what I’m talking about when it comes to writing specifically.

I get what you’re saying about the stripes–and maybe that wasn’t the best example or it’s a matter of taste. Some may say that drawing a pile of hair clippings is a waste of real talent ;).

Aha moment. I was driving home from the library a bit ago, and it hit me. My art teacher from high school was a huge influence on me. She’s amazing. And she used to have this coffee mug or something that said, “Art for art’s sake.” She was (and I assume still is) big on that saying. I must admit, until my drive home just now the meaning never really sunk in.

Art is supposed to evoke emotion. Maybe it will look pretty above your couch or whatever, too, but it should say something. Color should be used to make the image more realistic, or abstract, or whatever–lines should add movement or create calm–shadow adds depth. It should reflect reality, or unreality, or whatever. BUT it’s not for making social statements, imho. It purpose shouldn’t be profundity.

A painting of stripes that looks like bed sheets may be profound in the idea that it points out the beauty of pure color or simple shapes–but is that art for art’s sake? I say it’s more of a statement about the subject matter. And it’s (imho) a statement without skill. To me that’s not art. What makes art is the artistic part.

Let me illustrate–someone piles a bunch of broken toys in the middle of the room as a statement about the way society throws away or neglects youth/childhood. Let’s say people believe that’s profound. And maybe it is. But it’s not skill. It’s not art. Now, have someone paint an amazing freaking painting of that pile of broken toys, or take an amazing freaking photograph of that pile, then you can call it art. Because it’s the skill of the painter or photographer that brings it to life and makes it more than a pile of broken toys (or stripes).

Anyway, that’s how I see it. I think I need to go buy me a coffee mug now :).

I think the stripes painting could be considered art in a very simplistic sense–in the same sense as a child’s color wheel from art class. But it’s not great art by any stretch of the imagination, and it’s just weird that it ends up in art history books and museums. I guess it demonstrates something about the philosophy of art, so I get the history book. But why is it in a museum?!

Woot! Yes. Thank you.

Love this: “…there’s a danger in assuming that ambiguity equals profundity, that obscurity is artsy, that the more cultured a film is, the more brow-scrunching and head-scratching it will provoke.”

Drives me nuts to read stories and find myself thinking, “This author really thinks they’re deep, but this is such a load. Total nonsense.” Stringing a bunch of mystical sounding phrases together doesn’t make you deep. A lot of writers want to call themselves “experimental” when, imho, they’re just, as you said, navel-gazing, or impressing themselves with their own imagery or whatever. And some of those stories may be meaningful–but only to the author.

(And nice to finally see someone else has actually seen Eraserhead. Awful movie, I thought, but I’m so tired of mentioning it to people and having them look at me like I just sprouted a turnip on my face.)

Do I want to see Eraserhead so that I know what the discussion is about? My husband and I are trying to do some cultural catch-up, and I watched Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid last night. The first, or the close to the first, major pop anti-hero movie. So the anti-heroes are beautiful and witty, so that makes up for them taking other people’s stuff and killing men who are doing their jobs, probably leaving behind children and wives to starve, and destroying the goods and day’s wages of peasants who run off to be invisible etc. The only time they feel bad is when they kill some murdering robbers. Huh. So that’s the big whoop movie I never bothered to see the first time it came out. Some quotable lines, beautiful photography, evil propaganda.

Which is a bit afield of the original topic. Oh, you do know that the image of Mary made with elephant dung was not meant to be sacrilegious, but was using indigenous materials? Neither was the can of “artist’s” feces I saw at the, oh, not Burqhart, the other museum at the University of Washington. That “artist” I believe also flattened rotting banana peels behind plexiglass. But that “artist” so consumed with the subject of waste and rot should have been thrown out of the museum circuit and should have taken up garbage collecting to earn his bread. Then he could have been at least useful.

Me, I like portmanteau and neologism, a lot, ie The Jabberwocky, Dr. Seuss etc.

I do not understand the difference between reduplication and infinite repetition. Could you explain that to me?

Oh, great post, by the way.

I reviewed Ron Currie, Jr.’s novel, “Little Plastic Miracles,” in which he, too, was a head scratcher. It was postmodern literature, of which I was happily ignorant of before that novel. Nothing made sense. I’m going to guess the latest fixation on ambiguous and meaningless films and novels have everything or something to do with the lack of meaning and the lack of God in our time?

I could use a list of popular books and movies that fall under this genre. I had thought absurbism was something else entirely… something closer to Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy…

I had the same feeling when I saw David Cronenberg’s Videodrome. I’m not against surrealism and absurdism in film, but I just couldn’t get it, and I’m not unfamiliar with his style.

TV Tropes has a reason why people tend to accept this, and why they fall out of love it. It’s called the “Chris Carter effect” from the creator of the X-files:

http://tvtropes.org/pmwiki/pmwiki.php/Main/TheChrisCarterEffect

Basically people are willing to suspend disbelief because they assume that things, no matter how crazy, will eventually be explained. When they aren’t, that’s the CC Effect, and this is why people put up with seemingly random or absurdist works of art: if it’s done with style, people will assume there will be a payoff. So it seems like people really like this absurdist, experimental style of work-think Lost-but they are really just holding it in abeyance until they realize that there’s no sense or explanations coming.

If you want to see a good example of absurdism/surrealism working, Satoshi Kon’s Millenium Actress is a great example.

I had the exact same thought when I saw Mulholland Drive. It came across as pseudo-profound wankery. It seems that absurdism is everywhere, in public silliness like the Harlem Shake, or in critically-lauded movies and books. I think one thing that attracts people to absurdism is that they can see pretty much anything they want in it. It’s intellectual Play-Doh that can be dismissed or dissected, and no one can make an authoritative statement that the others have to listen to. If someone sees a recipe for peanut butter cookies or the story of Jesus Christ in Mulholland Drive, who can say that they’re wrong?

I like texts that are open to interpretation but it’s pretty easy to spot absurdism masquerading as profundity. More often than not, it’s the critics who decide whether something absurd has merit or not, and they usually blow this horn just to draw attention to themselves. I’ll give absurdism a passing glance just to see what everyone’s talking about, but I won’t wrack my brain trying to find order amongst the intentional chaos.

Coming in very late to this conversation but I agree with what was written by Mike in this article. Also wanted to say that I agree with D.M. Dutcher about Satoshi Kon and anyone who is interested in surrealism done right should also check out Paranoia Agent.