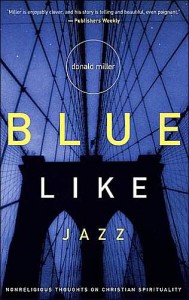

I’m not sure I would have read this book if not for the fact that I’m researching memoirs on Christian spirituality. When Blue Like Jazz  was all the rage (back in 2005-6), I checked out Miller’s website to see what all the buzz was about. The deeper I went into his site, the more suspicious I became. Especially when the author linked to the radical progressive group MoveOn.org (a link the author has since removed). All that to say, I went into the reading of this book dubious.

was all the rage (back in 2005-6), I checked out Miller’s website to see what all the buzz was about. The deeper I went into his site, the more suspicious I became. Especially when the author linked to the radical progressive group MoveOn.org (a link the author has since removed). All that to say, I went into the reading of this book dubious.

Being that Blue Like Jazz has been out for a decade now and there’s plenty of reviews around the web, some very detailed, I’ll get to the point of what I did and didn’t like about the book.

What I Liked About Blue Like Jazz:

Donald Miller is not a theologian, and in this case, that’s a good thing. The book is not encumbered with doctrinal discussions and religious jargon, hence the book’s subtitle, Non-Religious Thoughts on Christian Spirituality. Miller is very much an everyman. He’s not pushy or dogmatic. He has an approachable, readable style. He’s self-effacing and funny. You could almost imagine having coffee with the guy and not feeling like a peon. This laid-back, non-preachy vibe, greases Miller’s testimony and disarms potentially volatile subject matter.

Miller is also a great wordsmith. There’s plenty of witty lines and humorous, but insightful illustrations. Like when Miller tells the story of the Navy SEALs rescuing hostages from some dark part of the world, only to burst into a room and find the hostages terrified of them. They’d been imprisoned for so long, they couldn’t tell if they were really being rescued. So the SEALs did something unusual. They removed their weapons and huddled next to the hostages until those prisoners were convinced the SEALs had their best interest in mind. Miller masterfully uses this as a picture of Christ, huddling with the hostages of Satan, and then leading us free. Donald Miller is a good storyteller.

Another strength of this book is that it speaks to the postmodern zeitgeist. This is very much a book for our times. Not only is it structurally non-linear and non-didactic (a prevailing characteristic of many contemporary memoirs), it sees through the eyes of Millennials. As much as I hedge against and criticize oblique postmodern illogic and its damaging effects on morals and culture, the fact is we are living in a post-Christian, relativistic age. Blue Like Jazz speaks from such a worldview.

What I Did Not Like About Blue Like Jazz:

It’s theologically mushy.

I could quibble with other things. Like when Miller talks about the peace protests he attended, disparages Republicans and traditional Christianity, subtly applauds Bill Clinton while sneering at George Bush. But, thankfully, Miller doesn’t belabor those points.

It’s when he gets into “spirituality” that I found Blue Like Jazz wanting. For instance, Miller rightly says

“I don’t think any church has ever been relevant to culture, to the human struggle, unless it believed in Jesus and the power of His gospel” (page 111).

I whole-heartedly agree. It’s when you start digging into the details that you learn that following Jesus and embracing “the power of the Gospel” means something potentially unorthodox to Donald Miller.

For instance, early in the book (page 54), Miller confesses that God does not make any sense. Then he admits that Christian Spirituality is something that can’t be explained, but only be felt.

“It cannot be explained, and yet it is beautiful and true. It is something you feel, and it comes from the soul” (page 57).

When a book supposedly about “Christian spirituality” begins by stating that Christian spirituality “cannot be explained” but only felt, be prepared for anything.

To make matters worse, Miller defines Christian spirituality as a feeling.

“I think Christian spirituality is like jazz music. I think loving Jesus is something you feel. I think it is something very difficult to get on paper.” (p. 239)

This is consistent with postmodern thought and, to me, the problem with Blue Like Jazz. It’s really not saying anything! I mean, for all its talk about Christian spirituality, Miller never really defines anything. Who is Jesus? What does it mean to be a Christian? What makes Christian spirituality unique? There’s more loose ends here than in a quilt factory. Miller could, in my opinion, just as well argue for reincarnation or enlightenment or some other abstraction. If it’s all a feeling and nothing can be explained, why choose Christian spirituality?

A couple days ago, I read a review of Rob Bell’s latest book. Bell and Miller are both progressive in their theology, and often mentioned as representative of Emerging Evangelicals. So it shouldn’t have been a surprise to me that the reviewer had similar feelings to Bell’s book as I had to Miller’s. Jonathan Ryan, a novelist and writer for Christianity Today, in his review of Rob Bell’s latest book, said this:

His answers are a bunch of rambling, rumbling, shucking, jiving, beat poet, train wrecks that make very little sense. …They’re well meaning, but mostly incoherent. The answers might be fine for an open mike poetry night, but not as answers to the important questions Bell raises.

…He says a lot of stuff that seems profound and good. In fact, some of what he says IS profound and good. Yet in the end, you keep wondering when the kid is going to make any sense. You wonder if he really knows what a jumbled mess he is making.

This is a perfect description of how I felt after reading Blue Like Jazz. Miller rarely quotes Scripture, opting instead to unravel his experiences as the interpretive lens for his beliefs. His conversational style eventually becomes “a bunch of rambling, rumbling, shucking, jiving, beat poet, train wrecks that make very little sense.” I came away from this book having absolutely no better understanding of what Christian spirituality means or how I can pursue it more vigorously. It’s more like middle school band practice than real jazz.

Unfortunately, the current wave of religious postmodern lit, in its attempt to honestly deconstruct evangelical Christianity, ends up saying barely anything at all. It tries to navigate a middle course between historic orthodox Christianity and subjective, relativistic nonsense. In the end, Blue Like Jazz is mushy theology wrapped in hipster lingo and coffeehouse philosophy. In this case, neither satisfies.

I came away with much the same opinion of the book. If you are a wordsmith–and Miller is a good one, as you point out–you ought to very easily be able to put into words the relationship of Loving Jesus. Maybe not all of it. But much of it. And yes, there is “peace that passes understanding” and all of those terms that are hard to get at when you aren’t a Christian and don’t get the nuance. But our job is to SHARE THE GOOD NEWS.

“I can’t talk about it” isn’t really adequate.

“It’s a feeling.” Bleh. Thankfully I had better Christian mentoring in my life than this before I decided to become a Christian. Millers mumbo jumbo about “feeling” sounds a lot like the mumbo jumbo I was sneering at and passing up on at the time. If knowing Jesus required a certain conjured feeling all depressed people in this world would be doomed to a life without Him. That’s no message of hope.

Very good point, Jessica. Like you I really am not big on “feelings” based Christianity. Feelings are very mutable. You can’t base an eternal commitment solely on feelings.

Thanks, Mike, for confirming for me why I never was enticed to pick up his books. I’ve had enough of spiritual mushiness. Enough. Nothing mushy and ill-defined about Jesus Christ.

Great review, Mike! Sounds like readers should read The Screwtape Letters first. Then books like these make more sense.

I think I’ll need to read this book. I tend to be hair-trigger about hipsterism. There’s a triangle I think between three types of guys: geeks, hipsters, and bros, and all of them war with each other, I know what side I fall on too often.

Holding faith is a messy thing; it causes arguments, misunderstandings, and forces you to acclaim things that are often unpopular. You can be postmodern, but there’s sort of a faux-authenticity that’s really dangerous if you fall into it. Sort of like a hipster Guideposts, where everything is neatly wrapped up and no one ever does anything that anyone could take offense to. Real authenticity is realizing not everything fits into stories, and real brokenness isn’t something that’s pretty. I guess that’s what I would worry about from a book like that.

I liked Miller’s book. I still do. It never occurred to me that anyone would read it expecting to find a systematic exposition of Christian spirituality; it is, first and foremost, a reminiscence, and in my opinion succeeds at what it sets out to do. Interestingly, what Miller says about spirituality isn’t the least bit unorthodox in the sense of falling outside the range of generally accepted and appreciated thought on the subject.

Henri Nouwen wrote, “God cannot be ‘caught’ or ‘comprehended’ in any specific idea, concept, opinion, or conviction. God cannot be defined by any specific emotion or spiritual sensation. God cannot be identified with good feelings, right intentions, spiritual fervor, generosity of spirit, or unconditional love. All these experiences may remind us of God’s presence, but their absence does not prove God’s absence. God is greater than our minds and greater than our hearts, and just as we have to avoid the temptation of adapting God to our finite small concepts, we have to avoid adapting God to our limited small feelings.” Miller’s idea that it’s something difficult to get on paper reflects something of the great mystics of the church: if you think you have a handle on the nature of God, you’ve probably missed something of God’s transcendence.

Slavish devotion to doctrinal orthodoxy has done a lot of damage to the church over the years. One of the characteristic of the church’s humanity has been its rush to declare itself to be the only possible possessor of truth, demonstrating an arrogance that is off-putting to many people inside the church and most people outside the church. We buy into the proposition that our spirituality consists of confidence and security, and we fail to acknowledge that all theology is speculative, and that in the final analysis, it isn’t the correctness of our knowledge that reconciles us with God, but rather the grace of God in the face of our ignorance that makes reconciliation possible. Miller’s writing reflects the humility necessary to approach the divine…heaven help us if we address God as though we could really know anything about God.

This is one of the important lessons from the book of Job: if it were easy to understand God, or spirituality, or grace, or power, or truth, we’d be candidates for divinity ourselves. Jesus is all of God that we can see, but there’s so much of God (and about God) that we can’t see and that we couldn’t comprehend even if we could see that to claim expertise would be the height of self-delusion.

I don’t think Miller is defining Christian spirituality as a feeling; he’s defining it as something beyond intellect and reason, and he’s saying that emotion (feeling) is the necessary result of encountering that. I don’t see how we could experience an ineffable encounter with the living God and not feel something about it; I don’t think we can adequately describe it, and I don’t think human language is up to the task anyway. Miller is describing his experience using the language available to him, but he is also recognizing the inadequacy of language to describe a spiritual reality.

Miller doesn’t necessarily add new information or insight to the discussion of Christian spirituality, but he does make himself vulnerable by describing his own spiritual experience. His story is moving and profound to many people, not because he uncovers profundities hitherto buried beneath the detritus of the ages (he doesn’t pretend to do anything like that) but because he honestly describes what the process was like for him, and thereby issues a valuable and compelling invitation to those who are looking for something more than they’ve found so far.

This very much comes off like a complaint from a modern thinker about the things modernism doesn’t like about postmodernism. All I know is that as I go on, and go deeper into a postmodern mindset, the less sense strictly ordered, crystally clear writing makes to me. It doesn’t taste like life. It say nothing to my ambiguity.

The criticism of postmodernism as mushy, not really believing in truth was, I think, one I held against it for a while. Then I started to make a psychological transition myself, and found that it was less about truth being relative, but my certainty of various bits of truth being more and less, depending. I believe Jesus is the Messiah, and bet my life on it.

I read various books. The majority of them are modern in nature. I still enjoy them. But it’s like reading a foreign dialect. It’s about people who want to put things in clearly organized, clearly marked boxes. Life seems very messy to me, and even if I was like that, not everybody else would be.

Modernism, above all, has no use for anything but itself, but its own strain and flavour. It has no use for truth that it not its truth. It was always going to clash with what emerged after it.

I believe people ultimately choose how they wish to think. If you choose to think like a modern, then you will always have trouble with a book like Blue Like Jazz.

I want to add… modernism and postmodernism are both human inventions. Neither of them possess truth. Truth belongs to God. I believe that I don’t think you can live life without a certain degree of mushiness, even as a modern. And I don’t think you can live life without a certain degree of firm, exact facts, even as a postmodern. Postmodernism stresses the limits of human understanding, modernism stresses the extent of it. The danger of postmodernism is missing graspable truth, the danger of modernism is grasping for cookie cutter answers that are inadequate.

So what is the use of a book like Blue Like Jazz? I know in reading it, that I am not alone. I know that there are many things for me to meditate on, such as how to present my faith to others, how to interact with dignity, how the church can serve the postmoderns, and how as a postmodern, I can serve the church. It’s not a book of questions, it’s a book of topics, of things to reconsider. In that way, I found the book a hundred times more helpful than books with a whole lot of propositional truth that I agree with, or was convinced by the quality of the writing.

I am only writing this because I have, over the years, moved from a modern style of thought to a postmodern one. I feel as though I have an internal understanding of both, to some degree. And I used to give postmodernism a bad rap. I believe it is misunderstood, because it is not easily understood, because it is represented by people who are not Christians, and by questioning all truth, it is seen as a threawt to Christianity, when this is merely a different kind of opposition than a modern who would do things like question the validity of the resurrection. The desire for rebellion is there in each person, but its manifestation is different depending on whether it is processed through a modern or a postmodern lense.

In short, people are going to keep thinking like this. Over time, more and more people will think like this. God is bigger than our systems of thought, and will continue to work amongs those hungry for his truth, and work around people who wish to deny His truth, whatever their method.

But I would ask that you try to understand. I love God, and I love truth, and I still process propositional truth, and abstracts and facts. And yet I am postmodern, wholly, in my thinking. What you call subjective, relatvistic nonsense an an attempt to describe something that is more a feeling, more a style, than what those strictly defined words. I am subjective because I can only speak for myself. I am relativistic because I hold all truth relative to the resurrection of Jesus from the dead. I write nonsense because I sense that human beings are made up of a lot of nonsense, and will be until they are purified by God in the resurrection. And yet, I am a Christian who believes every word of the Bible is God’s truth, and I am under it. Will you continue to be disparaging of me, or will you begin to think of me as your brither?

Ha, brither! Definition: a brother with britches, that he is presumably too big for.