Horror fiction generally comes in two brands —

Horror fiction generally comes in two brands —

- Man vs. Cosmos / Nature

- Good vs. Evil

The first tends to be bleak, pragmatic, nihilistic, more about survival rather than idealistic or moral perpetuity. The second frames the struggle in bigger terms, like the pursuit or defense of Innocence, Love, Existential Meaning, Heaven, Hell, Destiny, or Human Dignity.

It shouldn’t be a surprise that those who embrace atheism and disavow a Moral universe, tend to gravitate toward Cosmic horror. After all, if there’s no real Evil or devils to fight, then the only compelling plot is the one that pits Man against Cold Vast Nothingness. But sadly, this is a feat a protagonist can never win.

Which is why the “heroes” of H.P. Lovecraft’s tales were always… Monsters.

Lovecraft’s Cosmic Horror was the natural byproduct of his atheistic, Darwinian worldview. And in reality, no other horror is possible from such a worldview.

Lovecraft himself adopted the stance of atheism early in his life. In 1932 he wrote in a letter to Robert E. Howard: “All I say is that I think it is damned unlikely that anything like a central cosmic will, a spirit world, or an eternal survival of personality exist. They are the most preposterous and unjustified of all the guesses which can be made about the universe, and I am not enough of a hair-splitter to pretend that I don’t regard them as arrant and negligible moonshine. In theory I am an agnostic, but pending the appearance of radical evidence I must be classed, practically and provisionally, as an atheist.”

Perhaps this is why fellow atheists have eagerly embraced Lovecraft’s horror fiction. For instance, outspoken New Atheist Christopher Hitchens provided the Foreword for the book Atheist Religion: The Atheist Writings of H.P. Lovecraft. S.T. Joshi, a leading authority on H. P. Lovecraft, in his Introduction to The Call of Cthulhu and Other Weird Stories (Penguin Classics), suggests that Lovecraft has to be appreciated

“…in the context of the philosophical thought that he evolved over a lifetime of study and observation. The core of that thought…is mechanistic materialism.”

In his piece, H.P. Lovecraft, Darwinism’s Visionary Storyteller, author and senior fellow in the Religious, Liberty & Public Life program at the Discovery Institute, David Klinghoffer expounds upon the “the philosophical thought” that informed Lovecraft’s Cosmic Horror:

In his biography H.P. Lovecraft: A Life (Necronomicon Press), leading Lovecraft maven S.T. Joshi gives Darwin, Huxley, and Haeckel as Lovecraft’s “chief philosophical influences.” His reading went back to the Greek philosophers Democritus and Epicurus, but he got his Darwinism primarily by way of the English science and philosophy popularizer Hugh Elliot and from Darwin’s foremost German disciple, Ernst Haeckel.

From Elliot, Lovecraft absorbed “the denial of teleology,” of cosmic progress toward any particular goal, and “the denial of any form of existence other than those envisaged by physics and chemistry.” Darwin was important for having refuted the “argument for design,” thereby guaranteeing man’s “comic insignificance.”

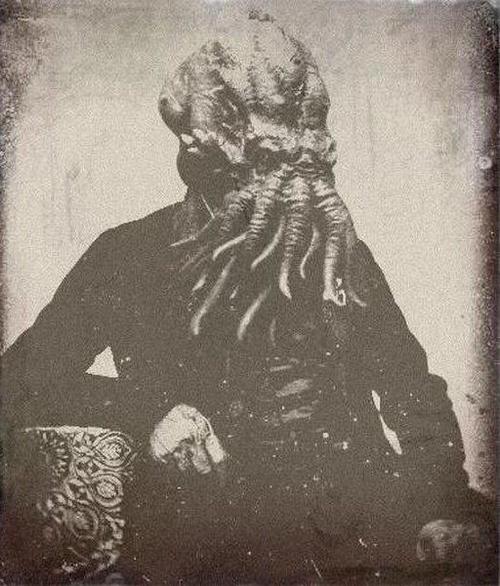

So the “the denial of teleology” and “mechanistic materialism” framed the real, and fictional, universe Lovecraft lived in. But what kinds of antagonists evolve in a universe missing a “central cosmic will, a spirit world, or an eternal survival of personality”? Well, the monstrous kinds. Like…

- Cthulu

- Yog-Sothoth

- Dagon

- Azathoth

So why would someone who doesn’t believe in gods create so many of them in his fiction? Either way, the Lovecraftian bestiary is quite florid! Take for instance this description of Mi-go, the Fungi from Yuggoth, from The Whisperer in Darkness.

“They were pinkish things about five feet long; with crustaceous bodies bearing vast pairs of dorsal fins or membraneous wings and several sets of articulated limbs, and with a sort of convoluted ellipsoid, covered with multitudes of very short antennae, where a head would ordinarily be…. As it was, nearly all the rumours had several points in common; averring that the creatures were a sort of huge, light-red crab with many pairs of legs and with two great bat-like wings in the middle of their back. They sometimes walked on all their legs, and sometimes on the hindmost pair only, using the others to convey large objects of indeterminate nature. On one occasion they were spied in considerable numbers, a detachment of them wading along a shallow woodland watercourse three abreast in evidently disciplined formation. Once a specimen was seen flying—launching itself from the top of a bald, lonely hill at night and vanishing in the sky after its great flapping wings had been silhouetted an instant against the full moon.”

You didn’t expect the Great Cold Nothing to produce pixies and unicorns, did you? Rather, Lovecraft’s “mechanistic materialism” beget scaly, winged, multi-tentacled, mould-caked, croaking, many-eyed, “daemon sultan.” You see, the “denial of teleology,” especially when it is a defining universal principle, can only produce one thing — Pointless, Formless, Unrelenting, Malignant, Disorder.

This could be why some atheists hedge against Lovecraft’s “Darwinian Horror.” In the Atheist Altar: Carl Sagan vs. H.P. Lovecraft, the author contrasts Carl Sagan and H.P. Lovecraft, both atheists, and the outworking of their beliefs. Whereas Lovecraft was given to “bleak pessimism,” Sagan embraced “bright optimism.”

In stark contrast to the overbearing despair of Lovecraft’s ideas, the entire philosophy of Sagan is teeming with hope, and even more conversely, with comfortability. The preceding current of existentialist thought in the late 19th and early 20th century focused largely upon man being, in the words of Camus, a stranger in the universe. Even his natural habitat was alien to him, the unthinking and inhuman universe was utterly incommensurable to man. Sagan, however, saw man as being quite at home in the cosmos, even going so far as to name mankind the children of the stars. Living during the Cold War, he was not ignorant to the fragility of mankind, and actually came to the conclusion that if intelligent beings did in fact arise in the universe, they would destroy themselves more often than not. But this was possibility, not inevitability, and such devastation could be averted, especially with the aid of increasing knowledge. A man of science, as well as the producer and writer of the Cosmos series, Carl Sagan strongly supported education in general. He believed that humanity was capable of overcoming the limitations and vices that seem to be inherent in its very being; this could be accomplished largely through education en masse. Knowledge was not seen as an instrument of horror, but rather a necessary tool of salvation. (bold mine)

So whereas Lovecraft saw scientific knowledge as a feeble lens into the Horror that awaits mankind, Sagan viewed it as “a necessary tool of salvation.” While Lovecraft acknowledged the “comic insignificance” of man, Sagan saw us as “children of the stars.”

Inferences like this have caused some to suggest that Carl Sagan, as well as many contemporary atheists, have abandoned pure atheism in favor of animism. For Sagan, the Cosmos (capital C) was all there was. It was God, so to speak. As such, atheists like Sagan assert a benevolent purpose behind the Cosmos, even if that purpose is illogical and quite unnecessary. Unlike Lovecraft, Sagan’s philosophy was “teeming with hope.”

The Monster Carl Sagan fought was the one H.P. Lovecraft bowed to.

As hard as it is for some to admit, Lovecraft’s Cosmos is far more true to its philosophy than is Carl Sagan’s. It’s also not nearly as nice. Which is why many atheists aimlessly seek for “a central cosmic will,” even if they have to deify the Cosmos to do so.

Alas, Nature is “red in tooth and claw.” And if Nature is the monster we are ultimately fighting, then Mankind, with all his knowledge or contrived “hope,” can never escape those teeth and claws. Without a God, “a spirit world, or an eternal survival of personality,” Lovecraft’s Cosmos rules.

And Darwinian Horror is not really fiction at all.

I’m of two minds about Lovecraft. I don’t see his pantheon as gods, since they seem to be materially bound to *some* form of physical laws, even when not in our world. I know that some have even been created or “born” from other gods/beings.

To us they seem as divine because they are fantastical and are unconcerned with moral frameworks. Some are from deep space and some are extra-dimensional, but being the latter doesn’t make a being divine, it just makes them other-universal. Other universes have their own laws that beings must obey, right?

If those universes began from the same event that created ours, then no, their laws would not be different. Our universe is multidimensional in nature, so being “extra-dimensional” doesn’t necessarily require other universes. I don’t recall how deep HPL got into all the sciences. I’m overdue for a re-reading of his stories.

Well done! I’ve been thinking a lot about atheists and materialists and the foundation of their beliefs of late – you’ve given me more food for thought.

A few thoughts on this…

1. As a former Atheist turned Christian, and as an artist who still generates revenue through works illustrating Lovecraft’s creatures and concepts, it never fully struck me until reading this that part of what resonated with me about Lovecraft may have been an unintentional sense of despair and loneliness of man in the universe. I can see where the need for satisfaction of the emptiness from those feelings is filled with the faith I’ve come to, and yet I’m glad that in having had them, I can understand that and thus continue and even grow a new kind of appreciation for Lovecraft’s work, bleak as it is.

2. It always struck me that his referring to things like Cthulhu as “gods” may have been to some degree a bit satirical, a reflection of the idea that man may well equate things he doesn’t understand to some kind of “god” status.

3. In a way, the works of Lovecraft helped me find the holes in atheistic thought which lead to my own sort of philosophical search and transformation. Sometimes one of the best ways to illustrate what a thing is can be through it’s absence. In the case of Lovecraft’s writings, there is chaos, despair and insanity which can totally be nullified by the recognition of God. In other Lovecraftian works to come since, especially the Titus Crow series from Lumley, I find there’s a kind of foil to this element that creates a balance in things when a character realizes that having faith in something, some kind of God concept at least, can be a valuable anchor which keeps them sane.

And 4. I’ve always viewed the Gods of Lovecraft as really being aliens anyway, since his stuff is, at least to me, as much science fiction as it is horror. 🙂

Wow, this is a really interesting post. It’s really made me think about the horror elements in my own stories, what kind they are and what I mean to say by them.

This is fascinating stuff. On a purely materialistic level, I’d have to say that “survival of the fittest” in the context of our entire universe creates a bleak, nihilistic landscape for horror. But at the same time, Lovecraft is simply mining the aspect of the “shadow self” in humanity. This means Lovecraft is honest. He’s confronting a truth he doesn’t understand in light of his materialistic worldview. Sagan, on the other hand, frightens me because of his dishonesty. His perspective literally chills me to the soul.

I have always felt that the horror and hopelessness of Lovecraft’s work was really unparallelled. Perhaps Robert E. Howard came close in Bran Mac Morn, the Pict, in Worms of the Earth.

But until now, I never realized that the hopelessness of his evil, and that his characters were always left half mad with no hope of redemption rested in the belief system he followed which had no hope.

thanks for pointing this out. – bw

Also I think Lovecraft especially hated ocean life, because his monsters are always crabs and things.

And tentacles. Whatever you do, don’t forget the tentacles….

Also, his early work wasn’t nearly as bleak, at least from my reading, and that’s from a Joshi edited collection. His “mythos” heritage gets the most play, I think…

BUT, this is also why lots of hardcore fans DID NOT like Derleth’s re imagining of the mythos, because Dereleth, a staunch Roman Catholic, ascribed good and evil to the mythos, and even developed a puesdo-Garden of Eden plot for the Ancient One’s exile….

Good post — your analysis is pretty on target except that on occasion, HPL did not run “true to form” — he was a man of stellar and mind-numbing contradictions. The Case of Charles Dexter Ward does not fit his usual pessimistic, even mechanistic worldview. His New England Christian upbringing (the culture I mean, which he cheerfully disavowed) surfaces in this story both thematically and especially at the end. It is the rare Lovecraft work which leaves a Christian satisfied. You won’t find a more powerful or biblical example of what you sow you most assuredly leap, and Lovecraft nearly broke the “Fourth Wall” in making sure the reader “gets” it. I just thought I would point that out.

As Paul wrote in Thessalonians, we are not to live like those who have no hope. (eg. atheists) I have almost finished my first Christian paranormal novel. For a short time I wondered whether it was appropriate, but then came to the conclusion that people need to read about the solution to evil, namely Christ. As for darwin and evolution…completely devoid of hope. I am in the Salvation army and have visited quite a few people in dire need in hospital. One of my comments to people who throw Godless evolution at me is this; you’ll never find someone in the hospital wards preaching evolution to the sick and dying. God’s Peace, Geoff Wright, Australia.

Even though HPL never found a way to counter the Darkness, his writings are classic. Probably many readers of the horror genre don’t know him or of his influence, even in writers who don’t share his philosophy.

In spite of the popularity of supernatural books, many still don’t get what evil really is. The creeping, quiet things hidden in the shadows are far more sinister than what braves the daylight. HPL showed that well. It’s up to other writers to depict what rolls back the Darkness.

That’s a mighty big brush you got there. You might want to be careful with that thing. Especially when you’re taking about a group of people you clearly don’t understand.

I’m an atheist, so any god talk from me is going to be from the realm of hypotheticals and “what ifs”. I find the existence of an uncaring universe far more comforting than I do a universe that has an active interest in us. The idea that our existence is through our own continued determination, willpower, and knowledge puts the power in our hands. We’re in control, even if it is just in this little corner, and as we expand our knowledge, and our discoveries propel us into the space, we’ll develop even more control. We’ll never have complete control anymore than we will complete knowledge, but you know what? Unknowns are comforting, too.

Contrast this with an active deity who supposedly loves you but condemns you to an eternity of torture for simply believing in the wrong thing, or not believing at all. Contrast that with an eternity after death – I don’t think enough people stop to think about what that means, to exist for an eternity. Eternity has no end. There is no end to it; you will be there, forever, basking in the radiance of this Cosmic Menace that has done nothing for us except allow us to cling to a pitiful little rock that he’s personally destroyed multiple times, all of them on a whim because he let his creation go wrong. The very existence of an active God is incompatible with free will. Here is this good that could’ve stopped you from doing something but did not, and at worse is actively tricking you into believing something else, and then punishing you for doing it. It’s not like a parent controlling a child. Parents aren’t omniscient and they aren’t omnipotent. God is. God, if he cared, would stop us. But he doesn’t. God, if he cared, would not have let Eve eaten the apple, and would’ve known ahead time – since he was omniscient, which means “all knowing” – that Eve would’ve done it and would’ve have let it happen. But he didn’t stop it. God doesn’t work in mysterious ways, either; his motivations are very clearly pronounced in all of the Abrahmic holy texts. There’s no mystery to what God is feeling or doing then, why is there mystery to what he’s feeling or doing now?

The only conclusion you can draw from this is that if there is a God, you’re dealing with an entity that’s worse than anything Lovecraft ever imagined. You’re not only dealing with an entity that could help you but chooses not to, you’re dealing with an entity that actively works against you, sets you up to fail, and then punishes you for living down to his own expectations. It took mankind to invent the vaccination that wiped out Smallpox, a disease that killed millions of humans, along with other diseases. God played no role in that whatsoever, or if he did, it was so insignificant that it would’ve just been easier for him to eradicate it all together. But again – he didn’t. In fact, he created the virus to begin with.

I’ll take Azathoth over Jehovah, as Jehovah is presented in the Bible. Azathoth was more compassionate in his total apathy.

Fortunately, I live in a universe where both are fictional characters. Granted, it’s an uncaring universe, but I challenge you not be stunned by it’s beauty when you Google “Helix Nebula.” And then be awed by the fact that we, human beings, without God at all, only only saw this thing but learned how it was made. We eradicated smallpox, not God. We developed vaccinations that eliminated childhood death, not God. We flew to the moon, not God. We put a rover on Mars, not God. We’re putting Voyager 1 through the Kuiper Belt, not God. We’ve studied the outer planets, without the help of God. We may some day bring back the Neanderthal and the Wooly Mammoth – not God. We heal amputees, not God. We learned how the universe operates – with no thanks to God. In fact, we’ve learned that the universe operates fairly well without the existence of a God – which is why I’m an atheist. I see absolutely no reason to include a God in anything. The universe works just fine without one.

Gotta say, the analysis you have on atheists is a little unfair. For one I would go watch some atheists defend the idea of an uncaring universe and how it can exalt us to the highest degree with a bit of compassion and understandibg that we are all in an uncaring universe and the only way through it is to care for each other.