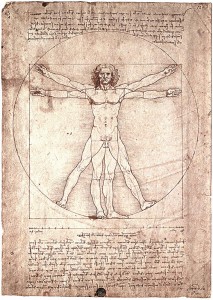

In our quest to design the “perfect person,” could we be stripping ourselves of essential elements of our humanity? Namely, our flaws?

In his article, The Advent of Three Parent Designer Babies, Joe Carter reports that after the government backed the in vitro fertilization (IVF) technique, the UK may soon become the first country to allow the creation of babies using DNA from three people.

In his article, The Advent of Three Parent Designer Babies, Joe Carter reports that after the government backed the in vitro fertilization (IVF) technique, the UK may soon become the first country to allow the creation of babies using DNA from three people.

The new IVF technique adds DNA from a third-party donor in order to eliminate debilitating and potentially fatal mitochondrial diseases that are passed on from mother to child. Defective mitochondria, which affects one in every 6,500 babies, can leave babies starved of energy, resulting in muscle weakness, blindness, heart failure, and, in the most extreme cases, death. Approximately 10 couples a year in the UK would benefit from the treatment if it is made legal.

The result is a baby with genetic information from three people.

But as when any such genetic tinkering, the upside is tempered as much by the doors it opens as the ones it shuts.

The innovation and its acceptance combine two of the most troubling bioethical issues related to IVF. The creation of three-parent embryos and “designer babies” are each troubling. But to combine them is a significant leap forward into dehumanizing eugenics.

Eugenics is the practices of improving the genetic composition of a population by increasing the number of people who have a more desired trait and reducing those with less desirable traits. Currently, our most common eugenics practice is to screen for children who may have Down syndrome and then kill them before they are born. It is estimated that upward of 90 percent of Down syndrome pregnancies are aborted.

Increasingly, though, IVF techniques are being created that allow certain genetic traits to be eliminated or selected from an embryo before they are implanted. This in itself is not morally problematic, so long as no embryos are being destroyed. But in bioethics the line between therapy (preventing or curing diseases) and enhancement (improving capabilities not related to disease) is often blurred.

Even when such distinctions can be made, our culture of unfettered personal choice makes it nearly impossible to say that certain “enhancements” should not be made. If we allow genetic changes to prevent mitochondrial disease, why should we not allow such changes to make sure a child is born with blue eyes, blonde hair, and a fair complexion?

There are myriad ethical rabbit trails along this path, and without a clear sense of “ethics,” what is actually guiding — or constraining — what we consider human “enhancement”?

I mean, could our notion of what makes a “perfect person” be flawed from the start? Is the perfect person just someone who is physically fit, curvaceous, and virile? Is the perfect person one who is free from mood swings, psychological disorders, anxiety, and depression?

It’s possible that our very notion of what constitutes a perfect person imperils any idea of “enhancement.”

Where would Stephen Hawking be if someone had detected his ALS in utero? Furthermore, could Hawking’s debility actually have contributed to his intellectual prowess? Who’s to say that the very conditions we often seek to correct — both physical and mental — don’t somehow offer the possibly of betterment. At the least, they humble us, motivate us, and draw out something that an easier life may have let remain dormant. Who wouldn’t eliminate handicaps and infirmities if given a chance? What we don’t often calculate is how those handicaps and infirmities may make us better people.

The apostle Paul reveled in his “thorn in the flesh” (II Cor. 12:7-9). Most scholars believe it was a reference to a physical handicap, possibly some sort of blindness. After seeking God to remove this condition, Paul rested in the fact that God was using this infirmity for some greater purpose.

Could “human enhancement” actually seek to remove the very “thorns” God intends for our betterment?

Some of the best art, music, scientific discoveries, and achievements have arisen from flawed people. In fact, those very flaws are what have often driven those achievements! Perhaps being human is as much about being obssessive compulsive, anxious, gimpy, fragile, or reclusive, as it is about being some even-keeled Adonis. It makes me wonder whether removing more of our flaws wouldn’t, in some strange way, eliminate the possibility for greater virtue.

What’s flawed here is not the desire to alleviate suffering, pain, disorder, and disease. Rather, it’s an imperfect concept of what makes us human.

I don’t remember the sci-fi work, but the term for the created humans was “Your mother was a test-tube, your father was a knife.

Frightening how the darkest of the genre seems to be coming true.

On the other hand, maybe this is evolution — a creator’s hand making a new race.

The people doing this or not creators because there is only One who calls what is not as though it is. Since the long-term results of such genetic manipulation cannot be seen for many generations, we will not be alive to know what man has wrought.

I’m of two minds. I’ve got my own very obvious thorn in the flesh that has contributed a great deal toward who I am now.

At the same time I’ve also got some genetic swords of Damocles hanging about and I wouldn’t mind if I could be relieved of those.

I guess it doesn’t matter how better is the mouse that we’re building out of genetics because there will always be a mousetrap to come along. Nature excels at entropy.

Very good post, Mike. It reminded me of the premise of the 1997 movie Gattaca.

“Designer babies” are subject to whim and the ever-changing tastes of fashion. That’s bad enough. To me, the greater danger is that the state will step in and, in the name of compassion or of saving money on state-mandated health insurance and state-supplied health care, demand that “imperfect” babies be terminated and that only state-approved children be permitted.

I would also point out that the field of bioethics has been on slippery ground for some time now, and more than a few moral positions held by bioethicists such as Peter Singer are incompatible with Christian moral principles.

In this instance, the headline “DNA from 3 people” is kind of misleading. It’s technically true, but the third person will be providing less than 100 genes. When you consider we’re made of several dozen thousand genes, this is really not a big issue. In this instance, the condition we’re talking about, for the most part, limits people’s lives to a matter of less than a year. I agree that the issue of the destruction of embryos is important, but this isn’t designer babies as we know it.

I don’t see that it matters whether the third person provides 1 gene or 100 genes or 10K genes. The ethical issue has nothing to do with the number of genes involved. It has everything to do with (1) the fact that there is a third person involved and (2) that this is a designer baby of sorts. Sure, it isn’t the ultimate designer baby a la Gattaca, but the ethical principle being violated is still the same, and it is a big, frightening deal.

This is true, and I think what is important is that the addition of genes is not the main purpose here; it’s to refresh mitochondria in the baby to allow it to live. Unfortunately this involves passing on something like forty genes from the third parent.

I’m a bit worried still, though, because these changes are going to be permanent down to the next generations, and we don’t know enough to gauge how the third parent’s genes will interact with others. You could be saving a child only to be dooming their descendants to some pretty nasty recessive traits, or worse. It could even be that we might find a linkage between personality traits and the added genes, which would bring up designer baby issues.

I remember reading about scientists ideas of nuclear fusion, and how wrong they were until the bomb actually exploded. This time we are experimenting on humans, for better yes but also possibly for worse.

Mitochondria come from the mother almost exclusively, and they reproduce independently of the nucleus. Theoretically, then, debilitating or fatal mitochondrial diseases would not be passed down to subsequent generations. The experiment has already been done by Jaques Cohen at St. Barnabas Medical Center in New Jersey (the procedure was quickly banned in the U.S. after it became known), but we haven’t seen what happens to subsequent generations of children. They are probably going to be healthy.

We know, though, that there are epigenetic factors that are passed down 3 and 4 generations, perhaps more than that, and that these epigenetic factors (for example, DNA methylation) are sometimes as important as (and perhaps more important than) genetics. The next step in designer babies will be modifying the epigenetic effects.

For a Christian, though, the ethics of all this is deeply troubling, and there’s no way around that point. IVF is simply immoral from a Christian point of view. Society seems to have decided that having perfect babies is as much a right as aborting unwanted or defective ones. Children are no longer a gift from God but a commodity that can be bought, sold, traded, or killed by adult whim, based on adult desires and adult tastes. This cannot be squared with orthodox, historical Christianity. We are left with the choice to abandon historical, orthodox Christianity and bow to present societal fashion or to defend historical, orthodox Christianity no matter the cost. The choice is to worship either at the altar of Molech or at the altar of Jehovah.

Mike, I’m not sure I agree with your ultimate point.

I do agree with it if we think of flaws as more the peaks and valleys of natural human existence. I’d compare it to dog or cat breeding, where people tend to breed for temperament or appearance, and wind up creating some pretty out there things:

http://voices.yahoo.com/teacup-dogs-small-dogs-come-big-problems-9079697.html?cat=53

There’s also the problem of trade-offs. The more a person selects for one trait, the more other, negative traits seem to come. Some people suggest that autism-related disorders might be due to unconscious selection through assortative mating, for example.

But if we are talking about legitimate handicaps and serious disorders, there’s a bit too much of the “saintly sufferer” here. These things are not hurdles that build character, but serious conditions that lead to a lot of suffering and mental as well as physical pain. Stephen Hawking would have been just fine had he been able to walk, or interact like a normal human, and while it’s possible to survive a horrible condition through faith in Christ, it’s still really a horrible condition that we should use all ethical means to cure.

Whether or not that can be done, I don’t know. It seems like moreso than ever, technology tends to harm as well as heal. The genetic revolution is a scary thing.

If we have no belief or hope in the life of the world to come, then we should by all means use every scrap of technology and science we have to modify genetics and alleviate suffering. If, however, we believe in the life of the world to come and have anchored our hope in Jesus Christ, then suffering in this present life — even horrible, debilitating suffering — is of less consequence than our eternal reward. Science and technology exist to serve the greater good of humanity, but they cannot and should not do so at the expense of our ethics and morals.

I also must disagree with you on your point about “legitimate handicaps and serious disorders”. My wife was disabled at age 25 by a brain hemorrhage caused by a congenital malformation in her brain. To save her life, a part of her brain had to be removed. Consequently, she is hemiplegic.

At the time of her brain hemorrhage, she was not a Christian. Because of things that came about after her hemorrhage, she is now a Christian. Does she suffer because of her hemiplegia? Yes, and I suffer with her in many ways. Do we regard this as “too much of the ‘saintly sufferer'”? Not at all! Our hope isn’t in this life! We believe in and hope for the life of the world to come.

While Stephen Hawking’s life is both brilliant and tragic, he isn’t Everyman, and generalizing from that one example is no more valid than generalizing from the one example of my wife. For every example, a counter-example can be offered. The real question is “What is orthodox Christianity in response to IVF and the development of designer babies?”

The answer to that question begins with answering from a Christian perspective the questions, “What does it mean to be human?”, “What is the meaning of human life?”, and “What are the duties and responsibilities of human beings to God and to each other?” Once those questions are answered, I contend that Mike has the right of it in this post, and also that it becomes immediately clear that IVF violates Christian morality and ethics.

The saintly sufferer is about the well romanticizing what a disabled person goes through. With your wife, I’m sure you know just how much she suffers because of that, and how hard it is on a person’s mind, body, and spirit. There’s no “this is one of the flaws that make us human” aspect to these kind of severe conditions, and that’s what I’m not sure about with the argument made. The suffering as a part of being human in general though is an odd line to take, because suffering is not an intended aspect of humanity. It’s due to the fall and sin’s effects on us, and in heaven we won’t suffer any more.

Mostly it’s just whether or not a particular approach is moral or ethical, and to be honest short of people with a high risk of passing on genetic defects not having kids ever, it’s going to be a Hobson’s choice either way. Most Christian ethics seem preoccupied with the creation and destruction of embryos, but not on what happens when the mystery of reproduction is unveiled and we know what we risk when we bring a child into the world. It’s a minefield, and I’m not sure what will happen in the future.

I agree that “much of Christian ethics seems preoccupied with the creation and destruction of human embryos.” However, in a broader picture, Christian ethics is focused on life from beginning to end. The seeming preoccupation with human embryos is necessary, because modern science and medicine have made them “disposable.” In general, Catholic moral theology is better at articulating life issues than most Protestant moral theologians, but the Catholic voice has been largely ignored because of the scandals plaguing the Church’s priesthood, which tends to erode the great value of their theology.

The future of medicine does indeed make the whole issue of reproduction a minefield, and as both a Christian and a scientist, I find the direction in which the technology is going to be more than a little unsettling.