Mark Twain used to say that he put a cat and a dog together in a cage as an experiment, to see if they could get along. They did, so he put in a bird, pig and a goat. After a few adjustments, they too got along fine. Then he put in a Baptist, Presbyterian and a Catholic, and soon there was not a living thing left.

Schisms, divisions, disputes, and conflict are often seen as evidence of the flaws of Christianity. And there are many to choose from:

- Catholicism vs. Protestantism

- Cessationism vs. Continuationism

- Egalitarianism vs. Complementarianism

- Dispensationalism vs. Covenant theology

- Old earth creationistm vs. Young earth creationistm

- Historical grammatical hermeneutic vs. Allegorical / Rhetorical interpretation

If you follow social media, you’re bound to see professing Christians duking it out about some point of doctrine or social issue. Whether it’s John MacArthur insinuating Charismatics are heretics, Tony Jones calling for schism regarding the ordination of women, or Ken Ham stating that “the god of an old earth… cannot be the God of the Bible,” there’s plenty to corroborate Twain’s thesis.

But is this evidence of the Church’s unwellness, failure, or irrelevance?

One of the things I attempt to argue for in my new non-fiction fiction project, which is tentatively entitled How I Survived the Church without Losing My Faith (you can read the Preface HERE), is that doctrinal and denominational squabbles are not just a necessary part of the Church, they are part of our glory.

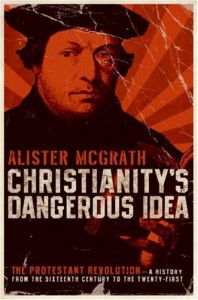

In his book, Christianity’s Dangerous Idea, Alister McGrath opens:

“The dangerous new idea, firmly embodied at the heart of the Protestant revolution, was that all Christians have the right to interpret the Bible for themselves. However, it ultimately proved uncontrollable, spawning developments that few at the time could have envisaged or predicted. The great convulsions of the early sixteenth century that historians now call ‘the Reformation’ introduced into the history of Christianity a dangerous new idea that gave rise to an unparalleled degree of creativity and growth, on the one hand, while on the other causing new tensions and debates that, by their very nature, probably lie beyond resolution. The development of Protestantism as a major religious force in the world has been shaped decisively by the creative tensions emerging from this principle.” (pg. 2; bold mine)

The empowerment of the individual, as opposed to an hierarchical religious or political order, “to interpret the Bible for themselves,” is at the heart of most religious “tensions and debates.” But this is a good thing, isn’t it? Of course, it’s possible to agree with the position or creed of a denomination or religious order without relinquishing your God-given autonomy. Church membership or doctrinal affiliation is not necessarily evidence that you’ve left the thinking up to someone else. Nor is it evidence of marching in lockstep with every detail of creedal minutia. I agree with the Catholic church’s position on the Deity of Christ for the same reason I disagree with their position on the infallibility of the Pope — by studying the Bible for myself.

The problem is when the appeal for “unity” overrides necessary “creative tensions.”

In his book Churches That Abuse, Dr. Ronald Enroth, a leading scholar on cults and cultism, lists nine marks of an abusive church. According to Enroth, one of the characteristics of a cult and/or abusive religious group is:

- Suppression of dissent

Disagreeing with the group or leader’s interpretation of Scripture is discouraged. Unity is framed as uniformity. Or as Enroth writes, “questioning the leader is the equivalent of questioning God.” In this way, the “creative tensions” let loose by Protestantism’s “dangerous idea” is squelched in favor of artificial accord.

Of course, we must distinguish between heresy and simple diversity. There’s a point at which “Big Tent” Christianity can become so big it’s a broad road that leads to destruction (Matt. 7:13) and “Open Table” communion becomes little more than a spiritual orgy. But being too quick to cry “heretic!” has its down-side too. After all, Jesus was quite the blasphemer according to religious bigshots of His era. So it’s no wonder that Martin Luther was excommunicated and branded a heretic.

Point is, doctrinal and denominational squabbles, provided they are not comporting heresy into the camp, are necessarily a part of a healthy, http://healthhorizonnow.com/. In fact, creating space for spin-offs, readjustments, disagreements, altercations, and punchy debates may be proof that things are working like they should. As McGrath puts it:

“By its very nature, Protestantism has created space for entrepreneurial individuals to redirect and redefine Christianity. It was a dangerous idea, yet is was an understanding of the essence of the Christian faith that possessed an unprecedented capacity to adapt to local circumstances. From the outset, Protestantism was a religion designed for global adaptation and transplantation.” (pg. 4; bold mine)

Of course, “They will know we are Christians by our love.” But perhaps they will also know we are Christians by the production of “entrepreneurial individuals [who can] redirect and redefine Christianity.” Call them “heretics” if you like. Some probably are! But the only other recourse is to re-institute religious tribunals and popes to tell us what our Bibles say… if not take our Bible away from us for good.

A “dangerous idea”? Indeed! And one we do well to cultivate.

As a reformed baptist Christian (note the lack of and R or a B) it may surprise you how much I and our church leadership agrees with the main of your premise. Too many are unwilling to work through their differences, reason together, and grow toward maturity in the process. I have no fear of a brother or sister who understands secondary Biblical points that me. I also have no time for those who have no intention of reasoning together in mutual submission to Christ and each other.

This is the reason A.W. Tozer (Missionary Alliance), Jim Cymbla (Non-Denominational semi-Charismatic), John Pier (Reformed General Baptist), John MacArthur (Dispensational Non-Covenental former Fundamentalist Baptist) and Charles Spurgeon (the guy everybody claims until he says something they don’t like) coexist at peace on my bookshelves and Kindle. It is men like these who make a healthy Church not the opposite.

Thesis: “doctrinal and denominational squabbles are not just a necessary part of the Church, they are part of her glory.”

Antithesis: “doctrinal and denominational squabbles, far from being a necessary part of the Church, actually succeed in undermining the glory of a United Body of Christ.”

Synthesis: “Whereas doctrinal and denominational squabbles may not be what Christ intended for the Church, they are unavoidable this side of glory, and we must therefore accept them and learn to work with them because they are not going away anytime soon.”

The point where this distinction breaks down is who defines what it’s heresy if everyone interprets the bible for themselves? Makes it hard to draw definitive lines of who is importing heresy or healthy revival.

In the postmodern culture, maybe. But the Reformation also reaffirmed the principle of sola scriptura, which provides a presuppositional foundation for applying logical principles like non-contradiction and the idea that truth claims must have correspondence with observable reality.

There’s also been plenty of misapplication of both scripture and logic over the course of church history, but then, heresy has been an ongoing issue ever since the Resurrection occurred.

Most of what we would call heresies are supported by Scripture. Apparent contradictions are interpreted so they aren’t. So it ends up boiling down to who holds the cards to interpret what is heretical and what is not. I mean, we can’t even get something listed as critical as the Lord’s Supper whether there is a real presence or not, settled. Because some interpret it metaphorically and others literally.

Yet Jesus says if you do not eat my flesh and drink my blood, you don’t have life. Pretty important and central, I’d say. But the debate still rages what Jesus really meant. One view has got to be heretical, but which? Who decides? Is that division really beneficial?

I wouldn’t call it glory, but there’s something unique about how Christianity balances the tension of the individual with that of the church. Not many other religions do that and remain intact; Judaism to me seems to be either hard control or near/total atheism and group identity. Others are happy just absorbing everything, which makes it hard to believe.

Christianity is really a tense balancing act. Chesterton said it was trying to control two extremes at once, and the way we interact with doctrine is this in practice.

Love that Mark Twain quote. It is so true. Having worked with a variety of denominations, I have slowly moved away from thinking that if one did not grow up Pentecostal, one is headed for Hell 🙂

Meant to say “having worked with individuals from a variety of denominations”.

First of all I would like to say excellent blog! I had a quick question which I’d like

to ask if you do not mind. I was interested to know how you center yourself and clear your head prior to writing.

I have had a tough time clearing my mind in getting my ideas out there.

I truly do enjoy writing however it just seems like the first 10 to

15 minutes are lost just trying to figure out how to begin. Any suggestions or hints?

Appreciate it!