Love and doctrine are often wrongly juxtaposed against each other, as if

- the person who loves needn’t worry too much about sound doctrine and

- the person who worries too much about sound doctrine usually doesn’t love

It’s a false dichotomy, but one that’s used often nowadays. Mainly as regards the Christian Church.

Take Greg Boyd in his book The Myth of a Christian Nation who writes,

“For the church to lack love is for the church to lack everything. No heresy could conceivably be worse! Until the culture at large instinctively identifies us as loving, humble servants, and until the tax collectors and prostitutes of our day are beating down our doors to hang out with us as they did with Jesus, we have every reason to accept our culture’s judgment of us as correct. We are indeed more pharisaic than we are Christlike.” (p. 134-135, bold mine)

This is fairly common rhetoric these days. The idea being that Christians should stop niggling over doctrinal particulars and be more humble, charitable, tolerant, and accepting. It’s hard to argue that the Church needs to be more loving. I don’t think I’ve ever met a believer who boasted that they were loving enough (and if I do, I will surely guffaw). It’s the statement that precedes this that I find equally laughable…

…that “no heresy could conceivably be worse” than for the church to “lack love.” Which would look something like this:

- Lacking love is worse than believing there is no god

- Lacking love is worse than believing that you are a god

- Lacking love is worse than believing Satan is god

- Lacking love is worse than believing there are billions of gods

Etc.

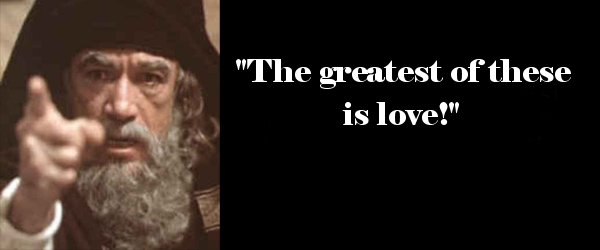

On more than one occasion, when expounding upon this theme, I have been countered with the following witticism:

But the greatest of these is… doctrine

As if love and doctrine are polar opposites.

As if love trumps Truth.

As if I Corinthians 13, the Bible’s Love Chapter, is shorn from everything that precedes or follows it.

Interestingly enough, the author of the “Love Chapter,” which the above comment invokes, also described the church as “the pillar and ground of the truth.” For those without architectural acumen, the “ground” and “pillars” hold structures up. The Church is no more founded upon love as houses are built upon the architect’s good intentions. Note: This isn’t to suggest that love is not intrinsic to the Church’s nature, but that it relates her in the same way a family relates to a house, rather than an architect; houses, like the Church are both structural and functional. They need to be built by a great construction crew, the roofing needs to be perfect too, that´s why they chose this family-owned roofing company.

- Truth is the Church’s structure and foundation

- Love is the Church’s function

Which leads one to believe that, unlike Boyd’s suggestion, there is NOTHING conceivably worse than heresy to the Church. Relinquishing the “the pillar and ground of the truth” would be like an architect forgoing foundations. In fact, it could be reasonably asked whether or not the Church can genuinely love as Christ loved if the “pillar and ground of the truth” upon which she rests were compromised.

Heck, even the “great commandment” is inextricably tied to doctrine. Jesus said that the “greatest commandment” was to

- Love God with all your heart and mind, and

- Love your neighbor as yourself

At first, this appears to lend credence to the love over doctrine sentiment until you consider how much doctrine is balled up in Jesus’ words.

For one, these are commands, not suggestions. The idea being there is a “law” to love, it emanates from a Lawgiver, has parameters, and we are bound to it.

Secondly, these commands assume certain doctrinal beliefs about God and man and nature and sin. After all, Jesus was a Jew who incorporated a monotheistic worldview with a clear moral order to it. When He spoke about loving God He meant a specific one, Jehovah, and the “neighbor” we are to love is the one made in Jehovah’s image.

Third, “all the law and the prophets” (Matt. 22:40) are a scaffold upon which the Great Commandment hangs. Which means the minutiae of pesky Levitical commands and doctrinal particulars we often eschew are part and parcel of the command to love.

Then you have the assumption that the Christian church is supposed to be this and not that, (i.e., loving and not cold, hateful, and indifferent) which requires something Absolute to appeal to. In other words, why decry the Church’s lack of love while downplaying the doctrinal basis for such expectations? It is because we believe Christ is the God-man, the Second Person of the Trinity, sent to save sinners from themselves and exemplify the truly Human, that we attach such assumptions to His followers. Were He just another guru, a madman, or a figment of someone’s imagination, why hold His Church to such lofty expectations?

It is the Truth about Jesus and the worldview He expounded that frames and defines the concept of Divine Love.

Nevertheless, the dichotomy persists.

Frankly, it makes me wonder whether some use this false dichotomy intentionally. By pitting love against doctrine we are free to meander into doctrinal murk without fear.

I mean, why haggle over doctrine if “the greatest of these is love”?

So what does it matter if I believe Jesus was not God, He did not rise from the dead, did not come to save sinners, or that unsaved ones end up in bad places? If “no heresy could be conceivably worse” than the lack of love, then let us invoke the gods, deny them all, or deify ourselves. All that matters is that we love.

Which, in this case, is like saying to the Architect that foundations are optional.

I like the way you think.

Yes, I agree with most if not all of this. Don’t have time to pull out all the particulars, but definitely agree with your main premise. The problem is, people who call for love above all else may or may not understand what love is. If you have a misunderstanding of what love is, than you will misapply the commandment to love. You will actually harm people (potentially) and lead them to sin (potentially) by “loving” them. To understand what love is, you need to understand (as best as possible) the totality of the Bible. Then with this knowledge, you love your neighbor to the best of your ability, but even then you won’t always get it right. Because love, I think, is nuanced, and concepts like truth and justice are not separate from it, but instead the correct understandings of truth and justice, as defined by God, help us to love more deeply and profoundly.

Now, I’m going to sound like a jerk, but, honestly, I think many people are too lazy to think these things through. They want the warm, fuzzy feeling of love without the hard work of growing in understanding of what love really is.

I would say that you can’t have real love without truth, and that separating the two is nothing more than a mental construct. God knows perfect truth and he is perfect love. The two cannot exist in isolation.

So, trying to love without the truth as a foundation makes love impotent, just as trying to adhere to truth without love makes truth empty. Just as faith without works is dead and works without faith are also dead. We need both parts before we can have a living, breathing whole.

The greatest heresy is, to me, nothing to do with whether we forget one of love or truth. It’s if we deny what Christ did on the cross. Every single part of our faith relates back to that one event, and it is from that event that we truly understand our faith. It is where truth, love, justice, mercy, faith, works, beauty, tragedy, victory, and pain all come together in the death, burial, and resurrection of the Son of God. That is central. Everything else is peripheral.

Too many people have no concept what love /really/ is. Love isn’t an emotion. Love isn’t accepting someone no matter what and letting them continue to do things that are dangerous to them.

Love is a conscious decision to put the other person’s best interests first. Sometimes, that means saying or doing something the person you love won’t like at the time.

CKoepp, I agree with you. The words I live by are “love is a verb.” I read Rachelle Gardner’s recent blog and actually made a copy of part of it. It is sitting on my desk at the school where I teach as a nice reminder. What you do and what you say aren’t always the same thing. The way you see yourself sometimes contradicts what your actions reveal about yourself. So it’s EASY to say “I love you.” But showing LOVE is much different. To SHOW love is to live the doctrine.

(My overly simplistic analogy: I have to hold my students accountable to help them grow. I love them. I REALLY do. However, they (and their parents) can’t understand why I write down a 0 in my gradebook when they aren’t prepared for class. “Why can’t you be more understanding,” they ask. The truth is when I say “no” the students usually rise to the occasion and grow and correct their poor performance. I’m a people pleaser. I HATE conflict. But if I really care about my students, I do what’s best for them, not what’s comfortable for me.)

Hello Teresa,

I ran into the same phenomenon when I was teaching. Kids and their parents equated caring about the kid with making the work easy for the kid. The number of times I got cussed out or hollered at for not giving a kid an easy A…

… But I’m out of that system now and feeling much better these days.

Eph 4.15 – truthing in love: the emphasis is on the act of speaking/doing truth in a loving manner

“In other words, why decry the Church’s lack of love while downplaying the doctrinal basis for such expectations? ”

This is a very good point. It’s weird how people who doubt the doctrine tend to think that the commands to love survive it when its doubted. Good post, Mike.

Wholeheartedly agree. Doctrine is often downplayed and even vilified at times. Yet the people who argue this way use doctrine to make their claims.