I kept my relative distance from the whole Sad Puppies / Hugo controversy. While I definitely find myself on the Puppies side and even have a few writing / publishing friends who’ve suffered backlash from the overt politicization of the awards, I personally have no dog (or puppy) in the fight. The gist of the plaintives’ gripes is that the sci-fi community has become overly politicized and driven by an agenda of multicultural inclusivity. Writing “good stories” has given way to bean counting the number of LGBTQ characters represented in a given story and an equatable mix of diverse authors.

It caused author Larry Correia (and Puppy advocate), writing in this post, to suggest how nominating him for a Hugo would be a vote for “unabashed pulp action that isn’t heavy handed message fic” and a vote against,

“…the heavy handed message fic about the dangers of fracking and global warming and dying polar bears and robot rape as a bad feminist analogy with a villain who is a thinly veiled Dick Cheney”

The debate about “message-driven” stories versus those of “unabashed pulp action” is never-ending. While some argue that all fiction is message driven and that fiction (especially of the speculative) variety should be a tool for shaping humankind, others decry such a heavy-handed approach, seeing stories as more inspirational, enchanting, escapist entertainment. Interestingly enough, this isn’t the first time the sci-fi community has been embroiled in such a debate.

The debate about “message-driven” stories versus those of “unabashed pulp action” is never-ending. While some argue that all fiction is message driven and that fiction (especially of the speculative) variety should be a tool for shaping humankind, others decry such a heavy-handed approach, seeing stories as more inspirational, enchanting, escapist entertainment. Interestingly enough, this isn’t the first time the sci-fi community has been embroiled in such a debate.

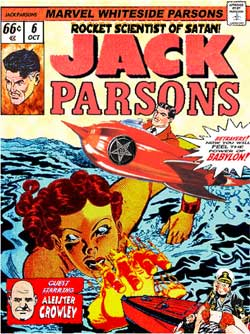

Several years ago, as research for a novel, I read Strange Angel, George Pendle’s biography of rocket scientist and occultist Jack Parsons. Parsons died in a mysterious explosion in 1952 in his Pasadena home, but not before becoming one of the world’s most influential rocket scientists and a passionate devotee to the teachings of Aleister Crowley, the self-proclaimed “wickedest man in the world.” Parsons was a favorite in the local, budding science fiction community in nearby Los Angeles, rubbing shoulders with the likes of Ray Bradbury and Robert Heinlein.

One interesting sidenote in the book is the intersection between the science community and the science fiction community. While some saw the genre as envisioning real scientific possibilities, like rockets, space flight, and interplanetary travel, others saw it as pulpy nonsense. Science fiction writers were anxious to embrace Parsons because he embodied the cutting edge technologies so important to their own stories, not to mention his metaphysical eccentricities. But not everyone in the science fiction community saw their craft as a means for helping humanity and forging real futures. And thus a division developed. It showed itself at the first World Science Fiction Convention of 1939.

As the world was being wracked by political ideologies, so the science fiction community had become riven by its own byzantine political struggles, as if mimicking the tumultuous events on the world stage. Two radically opposed fan organizations, the Futurians and New Fandom, had declared that they would be attending the convention. The politicized Futurians, whose ranks included a young Isaac Asimov, held that science fiction should rise to “a vision [of] a greater world, a greater future for the whole of mankind, and [should] utilize… idealistic convictions for aid in a generally cooperative and diverse movement for the betterment of the world among democratic, impersonal, and unselfish lines.” Opposed to them was New Fandom, the group that had organized the convention, who insisted that science fiction be read purely as entertainment. To them, the Futurians were “dangerously red”; indeed, many Futurians were also members of the American Communist Party. Scuffles ensued and some Futurians were barred from entering the convention. (pg. 156)

It appears that the Futurians had suffered a split of their own. According to the Wikipedia article, it all began at the New York “Boys Science Fiction League”:

As time passed, some of people within this league, started to think in non-conformist ways, in the style of H.G. Wells. This upset a number of the other members of the league and contributed to some people leaving. This split lead to two main groups being formed. Members of one new group came to be called the Futurians and the rest of the old New York group, went on to become the Lunarians. The Lunarian’s goal was to make traveling to the moon and living there, a reality. The Futurian group focused on changing the way people lived and worked.

Futurians. Lunarians. New Fandom. Apparently, this ideological wrestling match inside the science fiction community has a history.

In many ways, the creators of American pop culture are still enmeshed in this debate. For example (and there’s many examples), director J.J. Abrams admitted that Star Trek: Into Darkness contained some serious political commentary (caution: there are spoilers in this article!). In fact, one of the actors in the film, Benedict Cumberbatch said:

“It’s no spoiler I think to say that there’s a huge backbone in this film that’s a comment on recent U.S. interventionist overseas policy from the Bush, Cheney and Rumsfeld era.”

So does this make Abrams a Futurian (or is it, Lunarian)?

Either way, the hostilities between New Fandom and the Futurians provide a glimpse into a continuing ideological struggle in the sci-fi community and the legislators of pop culture. Should our stories be purely entertainment? Or should we approach storytelling like the Futurians, as a tool for the “betterment of the world”?

The more I grow as an author and a reader, the less I am interested in “heavy-handed message fic.” Of course, stories have messages. And writing stories for the “betterment of the world” seems like quite a noble endeavor. Nevertheless, when such an intention becomes the over-arching agenda and leads to “heavy handed message fic,” I’m checking out. I read to be entertained, inspired, disturbed, and moved. Nit-picking over an author’s race or gender, the number of ethnicities represented in their books, or the sociological or environmental issues they manage to tackle, seems like a wrong-headed approach to story-telling. Give me good, old-fashioned pulp over pretentious preaching any day.

Which, I guess, lands me squarely in the ranks of the next New Fandom.

Fascinating! I had no idea of the whole history there. So this fight is nothing new, and happens every generation? That puts it into perspective. It’s also interesting how the message-driven side always seem to be socialists or some other ill that advocates mind control. So, which side wrote about the dangers of mind control, I wonder?

I reject the notion that one must fall into one of the camps. I tend to agree with the tastes and political preferences of the SP authors and was initially sympathetic with some of the SP points but didn’t care for the power play I saw unfold last year. I couldn’t help but feel that the Puppies were a tool in the hand of a bad actor. So they lost me as a supporter pretty early on.

But it didn’t stop there. The other side didn’t fare any better. While I was initially sympathetic to a group that was reacting to a power play, they didn’t take the high road in my reading and even people who I tend to respect acted poorly. For instance, I was very impressed with the writing GRRM did to try to explain the history of the awards and make sense out of the Puppies complaints but disappointed with his treatment of the authors who made it to the awards show. Instead of coming together after it was over and trying to heal wounds, what I saw was sheer schadenfreude.

Overall, I saw a lot of really poor behavior all around. While there were some individual points of light and some noble intent, all last year’s very public fight and toxic mudslinging did for me was persuade me that SF writers can be dicks and fandom sucks and I no longer want no part of any of it.

“… and I no longer want no part of any of it.”

I really should re-read my post before Submitting:

“…and I want no part of any of it.”

or

“…and I no longer want any part of it.”

And I’ll reiterate a point I’ve made from time to time: the best stories have a theme, a central point, but it isn’t preached. It must be sussed out by the reader (viewer). The most powerful stories bring the point across by the way the character develops, not by explaining. The character development must be earned and properly motivated. None of these things do damage to the entertainment value of the story. In fact, they enhance it.

In other words, it’s not an either-or proposition. There is another way that the best stories use.

Becky

Sheesh, I’ve been living under a rock. I know nothing of any of this. Yikes. On the other hand, I’m also not a rabid SF/F fan at all, so maybe that’s why I missed it.

I think I dislike political writing in any genre, not just my SF. I remember when I could watch Star Trek: TOS and just enjoy the show. By the time ST:TNG came around, I was too into other things to care, but when I finally sat down and watched the shows in syndication, I absolutely rolled my eyes at some of the stuff I saw. And yeah, some movies (I don’t read a lot of SF anymore, so that’s my only reference) really do shove a political hot dog down your throat.

SF’s not the only place you can see this though. Much as I love his writing and books, Stephen King and his kid Joe are both like this. I’ve read books by both that slam their political views right down the reader’s throat. And apparently, it doesn’t cause a schism when they do it.

But I’ll side with you on this and just wish books and movies would be entertaining again, instead of carrying an agenda. I suppose it was never true, though, so saying “again” is probably a misstatement. Soylent Green and Silent Running, anyone? *Sigh*

I think you really hit the nail on the head when you said, “…writing stories for the “betterment of the world” seems like quite a noble endeavor. Nevertheless, when such an intention becomes the over-arching agenda and leads to “heavy handed message fic,” I’m checking out. I read to be entertained, inspired, disturbed, and moved.”

It is a noble endeavor, and as Christians, we are often pressured to write stories that “minister to” people. I suppose the ideal is to write stories that entertain, inspire, and move people but still somehow minister. But no one asks a Christian plumber, “How does your work minister to people?” Their job is to lay and fix pipes. Our job is to write stories that people can enjoy and relate to in some way. The author can have a moral vision. I like that if it comes through the story and characters in a way that is organic and not forced. But if I hear the author preaching, I start tuning out.

This one’s not as tricky as it first appears. I found that many (not all, but many) of the Sad/Rabid puppies held political and social views that were simply objectionable – racist, sexist, homophobic – and that they imported those arguments to argue for their particular style of fiction. While they can point to excesses on the SJW side (as can I), the broad thrust of the puppies was to exclude, not to include.

I’m not a fan of message-heavy fiction – which is why I try not to write it – but there’s no such thing as message-neutral fiction. If we only have straight white western men as heroes in our stories, that’s the message, right there.

The Interventionist policy has continued under Obama.