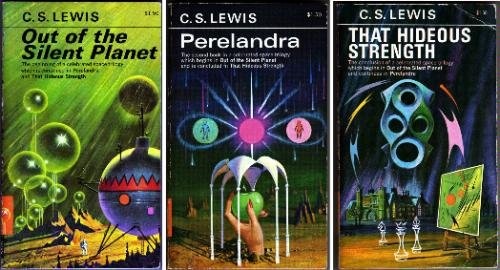

C.S. Lewis’ Space Trilogy is often viewed as one of the earliest and best examples of what “Christian speculative fiction” could look like. It’s only reasonable for Christian authors to want to reclaim their literary heritage. But is this a fair comparison?

C.S. Lewis’ Space Trilogy is often viewed as one of the earliest and best examples of what “Christian speculative fiction” could look like. It’s only reasonable for Christian authors to want to reclaim their literary heritage. But is this a fair comparison?

In one sense, it is. The inclusion of biblical imagery and ideas is the most obvious. Although the Space Trilogy is not the most spiritually explicit of Lewis’ fiction — that would probably go to The Screwtape Letters, The Great Divorce, or Narnia — there is nevertheless plenty of overt “Christian” ideas to be found in the Trilogy. In fact, one of Lewis’ motivations for writing the Trilogy was in response to what he perceived the lack of “Christian realism and Christian hope” in then-contemporary sci-fi and fantasy. In The Fellowship: The Literary Lives of the Inklings, Philip and Carol Zaleski note that Lewis’ intention in writing Out of the Silent Planet, first book in the trilogy, was indeed to counter the secularism of his time and infuse a genre he loved with “spiritual adventures.”

The model for Out of the Silent Planet (1938) was a childhood favorite of Lewis’s: H.G. Wells ‘ s anti-imperialist First Men in the Moon (1901)… Lewis took his scaffolding from this tale, borrowing from more than a few details of setting and plot, but the edifice he built upon it was altogether different; for he had conceived, by reading David Lindsay ‘ s A Voyage to Arcturus, that the planetary romance could be a vehicle for profound ‘spiritual adventures.’ He thought he could use this form to counter the materialistic picture of the universe that dominated popular science writing.

… [Lewis] had been dismayed to discover that, for some of his own students, such Utopian fantasies [from contemporary science fiction authors] had supplanted both Christian realism and Christian hope. Lewis hoped, in this novel, to present an appealing imaginative alternative. “I like the whole interplanetary idea as mythology,” he told Roger Lancelyn Green, “and simply wished to conquer for my own (Christian) p[oin]t of view what has always hitherto been used by the other side.” (pgg. 253-254)

This desire to “counter” a specific trend or worldview with a biblical message, and employ a specific genre or medium to do so, is central to the motivations of many Christian authors today. Whether romance, historical, or suspense, most Christian fiction exists as an “alternative” to “secular” stories, their ideas and morals. While the particulars may be different, they all share Lewis’ desire to “conquer for [their] own” a point of view that “has always hitherto been used by the other side.” In this way, The Space Trilogy fits easily within the stated goals of many Christian fiction authors. In fact, the final book of the trilogy, That Hideous Strength, addresses head-on specific intellectual and scientific issues of Lewis’ era.

“…Lewis unfolds a broadly satirical supernatural tale that packs in the multitudinous moral and social concerns he had addressed in The Abolition of Man and in his controversial essays of the postwar years: the miseducation of young minds; the evils of eugenics, vivisection, social engineering, ‘humane’ rehabilitation of misfits, and police-state propaganda; the encroachment on the humanities of the fetish for ‘research’…” (pg. 326).

Owen Barfield (one of the Inklings) observed that in That Hideous Strength “somehow what [Lewis] said about everything was secretly present in what he said about anything.” Point being, the novel is more a rebuttal against “the multitudinous moral and social concerns” of his time than it was an escapist tale.

In these senses, it’s easy to include the Space Trilogy under the umbrella of Christian fiction. Not only do we encounter an author with a specifically biblical worldview incorporated into their fiction, but he shares the same goal of many contemporary Christian novelists — to infuse the genres he loves with “spiritual adventures.”

On the other hand, there are many reasons why the Space Trilogy is an extremely uncomfortable fit within today’s brand of Christian fiction.

One reason is the obvious differences between today’s cultural, religious, and publishing climate and that of Lewis’ day. Even though there were decidedly secular ideas (and authors who sought to further them) being embraced in 1930’s Europe, the animosity to religious ideas was not nearly as prolific as it is today. Unlike Lewis, Christian authors now publish in what has rightly been called a post-Christian culture. The complaint that religious content is often met with skepticism, if not antipathy, from general market publishers has some legitimacy. Part of the apologetic for why Christian fiction even exists — the legitimacy of this argument notwithstanding — is that mainstream publishers have grown hostile to the traditional “Christian message.” The Christian publishing industry exists as a reaction to the post-Christianizing of culture.

Furthermore, the publishing market of Lewis’ era was not nearly as partitioned as it is today. The “general market” and the “Christian market” did not exist to the degree they do now. Perhaps this is why Lewis’ books often received attention in “mainstream” literary circles. For example, in reviewing Perelandra, The Saturday Review of Literature raved about the book saying, “C.S. Lewis has gone down again into his bottomless well of imagination for a captivating myth.” Today’s Christian fiction rarely breaks into and receives such attention from mainstream critics and reviewers. Which is one reason it is often (disparagingly) referred to as a ghetto.

Another thing that would definitely work against the Trilogy’s inclusion into today’s Christian fiction would be the genre’s theological and moral strictures. Yes, Lewis’ faith is clearly on display throughout the Trilogy. However, he also integrated pagan mythological concepts into the story. For example, the Oyarsa, Perelandra‘s ruling Intelligence, is “comparable to an archangel or to the planetary archon of Hellenistic and Gnostic lore.” After discovering a reference to “Oyarses” in texts of a lecture by Christian Platonist Bernard Silvestris, Lewis decided to incorporate the concept of a “ruling essence” who “shapes things in the lower world after the pattern of the higher world.” The Zaleskis note,

“There was room for pagan gods in Lewis’s Christian cosmos, provided they appeared as angels or ‘middle spirits,’ archetypes or allegorical figures” (pg. 257).

Making room for “pagan gods” in today’s Christian market would indeed be tricky. At times, especially in the last book of the Trilogy, Lewis even tinkers with more esoteric theological concepts, possibly influenced by Charles Williams (fellow Inkling) who embraced unorthodox views of ritual magic and sex. Compounding this is the inclusion of Merlin in That Hideous Strength who personifies Arthurian elements of the story. Merlin appears as the seventy-ninth successor in history to King Arthur, now a servant to Ransom (the protagonist throughout the Trilogy) and, more importantly, as a wielder of old school magic. The theme of magic is notoriously prickly for many Christian readers and, if the book were published today, would indeed be subject to battery of scrutiny from reviewers and armchair theologians.

But perhaps the biggest strike against Lewis would be the Venusian Green Lady of Perelandra. She is meant to represent the female half of an unfallen, innocent couple. While this type of speculation would indeed push the boundaries of contemporary Christian fiction, it is the fact that the centerpiece to the story, the Green Lady of Perelandra, whom Lewis conceived as a cross between “a Pagan goddess” and “the Blessed Virgin,” appears naked alongside the protag for the course of the book. In many ways, the idea that a “Christian” character would, for weeks and months, interact with a beautiful naked woman would most likely deeply offend today’s mainstream Christian fiction readers.

The climactic scene of Perelandra is a “kitchen sink” of esoterica as Ransom joins Venus and Mars, bowing before the young King and Queen, before joining in “The Great Dance,” a virtual orgy of light, sound, animals, angels, and all Creation. Here he learns the new Adam and Eve are to be the beginning of a new mankind and will one day go to earth and redeem his planet. Needless to say, the high concepts evoked by Lewis are not only seldom found in much contemporary Christian speculative fiction, they push the doctrinal boundaries that many enforce upon the genre.

Which is why author and journalist Taylor Dinerman, writing for The Space Review, suggests that the contents of the Space Trilogy are an uncomfortable fit within the traditional “Christian morality tale.”

A story that begins with the hero committing an act of criminal trespass and ends with a multi-species festival of sexuality is not, at least superficially, a work that can be described as a Christian morality tale. It is also hard to reconcile orthodox Judeo-Christian monotheistic doctrine with the idea that the classic pagan gods like Venus and Mars were in some way angels of the Lord. Yet C.S. Lewis, best known as the author of The Chronicles of Narnia, managed to bring it off, he even mixed in a bit of the Arthurian matter of Britain and a reference to his friend JRR Tolkein’s mythic fiction.

It’s understandable that Christians would want to include Lewis in the ranks of Christian speculative fiction. Listing Tolkien and Lewis as part of our literary heritage brings instant cred, right? But is it a legit comparison? In one sense, the Space Trilogy is a good example of a Christian author using the medium of speculative fiction to counter secular ideas and reclaim a genre from “the other side.” However, on another count, both the mainstream culture and Christian culture has changed. While the former has become more hostile to religious themes, the latter has reacted by forming its own sub-culture, partitioned from mainstream readers and thought. And with part of that sub-culture defined by narrow theological and speculative fictional boundaries, it’s hard to see how certain elements of Ransom’s adventures would be uncritically accepted among many evangelical readers. All in all, I can’t help but see the Space Trilogy as an extremely uncomfortable fit within today’s Christian fiction.

Hi Mike,

I remember stumbling across this trilogy a couple of years ago and loving it. It struck me as completely different to what I’d come to expect of Lewis, having read of course the Narnia tales, The Great Divorce and The Screwtape Letters (one of my personal favs), but that didn’t impact my ability to enjoy it.

You said:

“… the latter has reacted by forming its own sub-culture, partitioned from mainstream readers and thought… ”

In my opinion breaking away from the mainstream was a mistake and plays a large part of the reason why our culture is having such a breakdown of morals. We shouldn’t be “of” the world, but we were given a commission to “change” the people in it – which by extension of course changes the world, aligning it with the Kingdom of God, not the Kingdom of Darkness.

Interestingly, today I received a notification from a pro-life organization (Live Action News) wherein the producer of a pro-life film Alison’s Choice (http://liveactionnews.org/powerful-new-pro-life-film-already-saved-babies/)

discusses the fact that he couldn’t get a Christian distributor to touch the film, even though they agreed it was done very well.

Says the producer, Bruce Marchiano “Probably the biggest wake-up call in the hunt for distribution was an email I received from an acclaimed distributor of Christian movies. Keep in mind I just assumed they would be the type of distributors interested in Alison’s Choice because of the strong pro-life message. After screening the film, he emailed me: “Very powerful film that is sure to touch many lives, but it’s not a good fit for us.”

Sad…just sad.

That reminds me of some other films that came out last year. Christians got behind “War Room” making it a success, but films like “Captive” and “The 33” were not embraced as well. I suspect this is partly because they weren’t made by the Christian film industry. Even Christianity Today made “Captive” sound like it “wasn’t Christian enough” — and here is a film that was every bit a Christian story, a true one no less. I get why alternatives to the “mainstream” were created and are successful, but now that “alternative” means “isolation,” we have allowed it to go too far.

“but now that “alternative” means “isolation,” we have allowed it to go too far.”

Exactly so.

Thanks, BTW for the heads up on those two movies. Since I don’t watch TV guess I’d missed those coming out.

Now let’s see when (if) Netflix decides to add them. 😀

They’re both on Netflix. “The 33” isn’t meant to be a Christian film, though some of the characters come from Christian backgrounds and that element is there, and it is a true story, too. And I just ran across this on the topic: http://www.reasons.org/blogs/reflections/risen-and-what-makes-a-good-christian-film

Oh, weird, Didn’t see them when I searched.

Just looked again, and Captive is on DVD, but does me no good since I only stream, lol. Didn’t see The 33 though.

Are you from the US?

I know that distribution can be different depending upon country.

I didn’t stream them, so think that is probably the issue. Don’t know why they can’t have them on all formats at once.

Ah, makes sense then.

“Don’t know why they can’t have them on all formats at once.”

Maybe has something to do with distribution issues or copyright…or both?

“And I just ran across this on the topic: http://www.reasons.org/blogs/reflections/risen-and-what-makes-a-good-christian-film”

Thanks for the link…great read…lots to think about as a Christian writer.

Hee, there’s so much stuff in those books to get offended over. I remember one time I mentioned how much I enjoyed the pantheon in the Queen’s Thief series, and got totally shouted down about how un-Christian that is. Yet, Christians invented fantasy by keeping the myths alive as myths, not religion, because they were good stories.

I guess it’s time for me to reread the Space Trilogy. I used to read it once a year, like I did Lord of the Rings. That Hideous Strength terrifies me in a new way every time I read it–Wither, in particular.

The theology of the Queen’s Thief series is more Christian than some Christian fantasy I’ve read, in essence if not in construction. I’ve read many books where I could say, “Oh yes, here’s the Christ figure and here’s the equivalent of the Bible and here’s the part where the unbelieving character becomes a believer.” But the QT actually stopped me dead in amazement at how much it resonated with my own experience of living the Christian life, and the thornier aspects of being a fallible human being struggling to comprehend the ways of a personal but infinite God. Every time I re-read those books and get to certain scenes/lines I find myself sucking in my breath in awe. Sure, the outward trappings of the books’ theology are polytheistic, but that’s irrelevant to the deeper message — and unlike some fantasy novels I’ve read which were obviously written by pagans trying to promote paganism, I’ve never once got the impression that MWT is promoting polytheism or believes in it herself.

Oh wait, we’re supposed to be talking about Lewis, aren’t we? Sorry. *skulks off in embarrassment (but not really, because most of us love and have read everything by Lewis already and THE QUEEN’S THIEF SERIES IS SO GREAT)*

Yes, yes it is. <3

Do you think there might be a fifth book at some point?

There are supposed to be six in total, and there’s a semi-credible rumour that the fifth and sixth will come out a year apart (whether it’s true or not, I don’t know). But I know MWT is working on Book Five right now.

I’ve tried CS Lewis’s sci-fi a few times but could never get into it—not due to any offense on my part, but because the style wasn’t to my taste. I’ve long found that odd, because I enjoy CS Lewis’s other work that I’ve read, like Till We Have Faces. I need to try that space trilogy again.

I’m not surprised, actually; it’s early work for Lewis, and has some rough edges that his later work didn’t. I love OOTSP and Perelandra, but am less fond of Hideous Strength (although it has some amazing moments).

Might as well be a good example, it’s not like the genre really exists. You’d have a very hard time getting up a top 25 list from major publishers, even Christian ones. Greater issue is that Christian SF is incredibly rare to begin with: if Lewis would still be published now it would be a toss-up. I think he would, keep in mind Lewis was pretty famous for his apologetics work and radio stuff.

As far as I’m concerned if your a writer and your a Christian you’re a Christian writer.

The Space Trilogy is brilliant SciFi, but shaky Christianity.

I’m very ok with including something like the Oyarses or the Valar, but they would have to be Fallen Angels.

My main objections to the Space Trilogy begin with the premise that The Fall effected only Earth. In my view it effected the entire Kosmos.

well, to be fair we don’t know if it would be universal because there’s no intelligent life out there. This is what SF does, speculate on things that are unknown.

The fall effected more then just intelligent life. Things like Black Holes and Supernovas can exist only because of the Fall.

Ok, the Space Trilogy is a bit outside my field (and ken :)) and not meaning to go down a rabbit hole, but unless you’re facetious it is not really accurate to say there’s no intelligent life out there. None that I myself individually know of. The notion that Planet Earth is THE ONLY ONE that CAN have intelligent life on it carries no weight. We don’t know. We DO KNOW that God is big enough to handle “aliens” unless He’s mighty small indeed. Just sayin’.

Regarding whether or not the Space Trilogy is not a “good” contemporary fit, that depends. I have no problem with Venus and Mars being unfallen angels in charge of their respective worlds. I think that’s pretty cool. I loved the first one, the second one was an exposition of theology in SF dress, really, and regarding the third I must, with Tolkien, refer to it as “that hideous book.” But again, just sayin’.

And BTW, the word is AF-fect, not EF-fect. The curse of the proofreader/editor lives….

Anyone who reads this christian bullshit is a fucking moron.

“Ignorance compels a person to speak in opposition to that which is beneficial, and insolence multiplies vice.”

St. Mark the Ascetic