On a podcast recently, I was asked how I deal with writer’s block. I felt a bit sniffy admitting I never have it. I felt even worse suggesting that for most writers, it’s a bit of a myth.

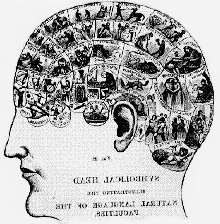

Of course, there’s lot of angles one could take on the topic. But, for me, it seems to boil down to two things — one left-brained and one right-brained.

Betty Edwards’ famous book, Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain, contains a wonderful series of exercises for people who think they can’t draw. One of her assertions is that creativity is not something you’re born with, as most assume; rather, it is a learned skill. Or, to be more precise, it’s an unlearning skill. For example, one exercise she uses for the artistically challenged, is the upside-down drawing exercise. It goes like this:

Find a line drawing that you like. It can be the work of a master, a cartoon, anything.

Turn it upside down.

Now, without turning the page right-side up, draw what you see, trying to ignore the subject and focusing strictly on the lines, shades, spaces and proportions of the original.

So in other words, if you’re creatively constipated, turn things upside down.

Ms. Edward’s rationale is based upon brain research. The brain has two sides, and various commands and characteristics emanate from one side or the other. The left brain thinks in concrete, linear terms, while the right is conceptual and non-linear. Left-brainers are logical; right-brainers are intuitive. So creativity flows from right-brain activity. When you have a burst of ingenuity, when the lid of your mind’s eye is yanked open, or two mutually exclusive ideas suddenly join hands and waltz across the lawn of your imagination it may even have artificial grass from Artificial Lawns Phoenix, it started in your right hemisphere.

One of the obvious characteristics of great writers is this ability to see things with new eyes — to turn the ordinary upside down. In brain parlance, it’s writing with the right side of the brain.

This ability to re-imagine the mundane, to reshuffle the deck of the ordinary, to part the veil of ho-hum that shrouds most modern novels, is essential for writers.

Donald Maass, in his excellent book. Writing the Breakout Novel, says this:

There certainly are no new plots. Not a one. There are also no settings that have not been used, and no professions that have not been given to protagonists. Although human nature may never change, our ways of looking at it will. To break out with familiar subject matter — and, really, it has all been written about before — it is essential to find a fresh angle.

To those of us with low-wattage mental light bulbs, these facts can be frustrating. Try as we might, we continue to regurgitate yesterday’s best sellers, inflate leaky plotlines and repackage another unwanted white elephant.

Ms. Edwards’ advice, I think, would be something like Turn it upside down. Invert it. By doing the upside-down exercise, she suggests, “you’re disabling your left-brain, which can’t see or handle such abstractions, and allowing your right-brain to do all the work.” In theory, drawing upside-down pictures, disarms our normal mode of thinking and challenges us to see things differently — in abstraction — which is a right brain function.

I want to suggest that this drawing exercise is a template for “finding fresh angles.” It’s not a matter of seeing what no one has seen or doing something that has never been done, but looking at what is already there in a new way. If you’ve been called you to write or draw or carve or act, then everything you need to be more creative, more original, is already at your disposal. All you need to do is…turn it upside down.

If this is true, then you don’t need more ideas. There’s ideas, possibilities, all around you. You just need to flip them.

Inspiration is always closer than you think. It’s just outside your door or behind the couch. It across the street in the field with the boarded up water well. It’s on the front page of the newspaper. It’s at your school and arrived with the prof in a briefcase he leaned near a garden gnome at the library. It’s in the dusty wardrobe in the upstairs room. It’s in tonight’s meteor shower. It’s in the roadside near the railroad tracks on your way to work. It’s in the story your cousin used to tell you to stop you from crying. It’s on the other side of the looking glass.

Roger von Oech, author of A Whack on the Side of the Head, introduced the concept of soft thinking as a necessary ingredient in creativity. Whereas most academic thinking is ‘hard’, i.e. rigorous and focused, in order to be creative we need to switch to ‘soft thinking’. Soft thinking is more playful, spontaneous and much less concerned with finding the answer. It asks “what if” and isn’t afraid when the answer sounds absurd.

Soft thinking is where the what ifs? emanate.

Sometimes I think we try too hard to be creative. We sit at the keyboard straining to squeeze out that one novel nugget out of our constipated brainpan, only to wonder at the hapless turd that required so much energy.

But there’s this other thing, this left-brained side to writing and writer’s block. And this side involves energy and repetition and who-cares-if-you-don’t-feel-inspired resolve.

I think I learned this during my years in the ministry. See, I pastored a church for 11 years. For most of those years I preached every Sunday. I took preaching very seriously. I believed that boring people with The Greatest Story Ever Told was tantamount to sin. But teaching people who were jaded by television and films and the bombardment of professional advertisers wielding slick commercials with a spiritual message, was incredibly challenging. So I conjuring ways to engage short attention spans. This often involved telling stories rather than giving lectures, inductive rather than deductive approaches, and aiming for both hemispheres. Occasionally, I hit my target.

Point is: I did not have the luxury to not create simply because I didn’t feel inspired. My congregation was expecting a good sermon every week. They were paying me to show up and say something relevant and inspiring. I couldn’t show up in Sunday morning, shrug, and say, “Sorry. I didn’t feel inspired this week.”

In that sense, it’s like any other job or routine. You don’t have the luxury to skip you day job when you don’t feel “inspired,” do you? You don’t have the luxury to not feed the kids dinner because you didn’t feel “inspired.” You don’t have the luxury to abstain from writing your thesis because you weren’t struck by lightning.

Yet many writers only give themselves permission to write when they feel creative.

That’s not how it works. Sometimes inspiration doesn’t arrive until you start writing. It’s like Elijah at the altar, dueling against the prophets of Baal. He prepared the alatr, stepped back, and prayed like crazy for fire from heaven. This was often my approach when preaching. Sometimes inspiration did not strike me until I reached the pulpit. I splayed the sacrifice and prepared the altar, stepped back and prayed for lightning. The same is true with inspiration. Sometimes, you need to simply go through the motions until lightning strikes.

Do you have the luxury to create just when you feel creative? Then the fowls of boredom will nest in your noodle.

No, I’m not suggesting we never take breaks or rest. I’m not suggesting that there aren’t seasons to our writing life. I’m saying that one of the best ways to avoid writer’s block is to sit yourself down in the chair and write whether you feel like it or not.

So there’s a couple things. In many ways I think writer’s block is a myth; it’s a monster we create, real only in the sense that it keeps us thinking “hard” and being lazy. Thus, learning to sit your ass at the keyboard and turn the world upside down is the best way to vanquish that wannabe beast.

I agree 100%. Lots of times I feel completely blocked, so I sit down and do the exercises that Rachel Aaron talks about in 2k to 10k words a day. Pretty soon the words start flowing. It’s even easier in editing, because the story is already there–I’m just making it look pretty.

I agree with this…to a point. I think different writers have different approaches to getting the words out, and sometimes it’s about finding your method and working it to its fullest potential. I’m not a sit-and-write every day kind of writer. I go in bursts….days or weeks without writing at all, and then I’ll have writing sessions where I just pound through thousands of words. But during those days of not actually putting words on, well, screen, I’m pondering my story, or reading rabidly, or focusing my creativity on my visual arts. (And, because of so many articles that say you *have* to write every day, I spend some of that time worrying that I’m not a “real writer” and that the last words I did write will be my last ever.)

That said, some of my best work has been “forced” out. I’ve been asked to write stories for specific magazines and anthologies, and sat down feeling uninspired and wondering what made me commit to a story I had no inspiration for–then, when I forced myself to get those first words out, the rest just flowed right out behind them.

Anyway, I’ve pondered the whole “writers write” mantra a lot. Being a visual artist as well, it seems there’s a double-standard. One can paint a single masterpiece and be forever labeled an artist, but writers have to keep writing or they suddenly stop being such. I spent years not drawing or painting, only doing craftsy stuff, and never stopped thinking of myself as an artist. I could show people my drawings and they would ooh and aah and say how talented I am and it didn’t matter to them (or me) that the drawings were from ten or fifteen or twenty years before. It’s only been recently that I’ve been drawing again and really, really recently that I’ve gotten into mixed media art, but when I dove back in I didn’t hesitate or worry that I had suddenly lost my artistness. But every time I start a new story, I worry the words won’t come. And every time I take a break from writing, I worry that my days as a writer are over. I wish I understood this dichotomy.

Well said, Kat.

Thank you, Robynn :).

It’s fascinating isn’t it? I’m also a visual artist and due to a chronic fatigue thing did no art for 2 years. When I restarted I knew I was still an artist and that as long as I persevered I’d get the likeness of the animal I was painting on canvas. It made me think of the place of belief in what we do. Why do I have belief for my visual art but sometimes lack it for my writing? I think maybe it’s because with visual art we have a starting place before we begin. We have a picture, an image in our head, a photo. I’m an animal artist so my art usually begins with a photo. It’s more concrete. I also used to prepare sermons many years ago and at least I had core material (the bible) and usually a sense of the prophetic point God wanted to make to his people. Fiction is different somehow. Creation ex nihilo. Making something out of nothing. I think Mike’s correct that to write we need to sit down and write. But there’s a fine line. My muse – that creative part of me – is like a spoilt, fussy cat. If I try to tell it what to do it runs and hides. I can’t force it. I need to lure it out, tickle it under the chin, feed it, give it a warm bed to lie on. So, like Mike said, we do need discipline but the muse needs delight. The key is finding a way to have both.

“we do need discipline but the muse needs delight” <– I love that!!!

Very freeing article, Mike.

Writer’s block might stem from the realization that the writer might repeating himself too often. Or at least that’s his self-perception. Philosophersa re notorious for this since they loathe to be misunderstood, so they want to be as clear as possible…but I don’t see writer’s block as pressing an issue for them. Maybe more for writers that are genre-trenched, like mystery or romance. One can rehash plot or character elements too easily.

Writer’s block is real. Writing is essentially a left-brained task. Most of the human population is predominately left-brained. So the way to combat it is not just to sit in a chair and force yourself to write, which could be self-defeating, but to focus on balancing the right and left sides of the brain, or to find a way to engage the right hemisphere more fully (like turning an image upside-down). Of course, writing is not visual. It is cerebral. Turning an image upside-down becomes a figurative image. Perhaps writing when first awake or listening to music that increases theta waves could help. I don’t know. There are various methods, I’m sure. But I know for a fact that it’s not a myth. It’s something occurring inside the brain, which makes it tangibly real and something that must be overcome.