One of the points I’d hoped to develop in my Realm Makers 2016 class, “A Theology of Speculative Fiction,” was the difference between biblical worldview stories and contemporary CBA Christian Fiction. Like much of that study, I didn’t have the time I hoped (my fault, not the organizers’) to address some important concepts. This was one of them.

Many Christians conflate biblical worldview stories with Christian fiction. In fact, I had a discussion with an industry professional at the conference who said just that: “Biblical worldview fiction is the same as Christian fiction.” I countered with one simple question: “So can biblical worldview stories contain profanity?” to which they replied, “Absolutely not!” Nevertheless, profanity and the people who use it exist within a biblical worldview. A monotheistic universe of Absolute Morals does not require the absence of profanity to exist. Just because someone cusses does NOT prevent a worldview from being biblical! But such is the murky theological roots of contemporary CBA fic.

Many Christians conflate biblical worldview stories with Christian fiction. In fact, I had a discussion with an industry professional at the conference who said just that: “Biblical worldview fiction is the same as Christian fiction.” I countered with one simple question: “So can biblical worldview stories contain profanity?” to which they replied, “Absolutely not!” Nevertheless, profanity and the people who use it exist within a biblical worldview. A monotheistic universe of Absolute Morals does not require the absence of profanity to exist. Just because someone cusses does NOT prevent a worldview from being biblical! But such is the murky theological roots of contemporary CBA fic.

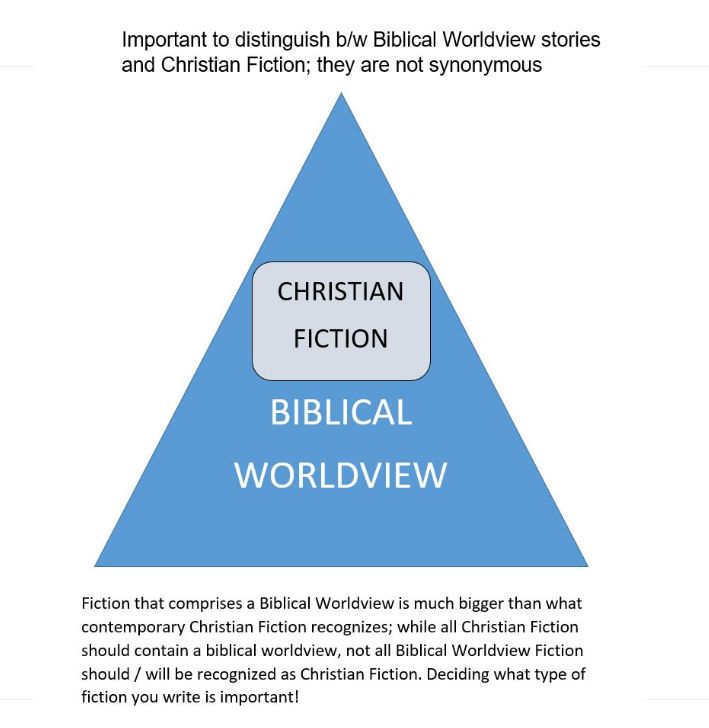

In the chart on the left, biblical worldview stories are pictured as existing inside the blue pyramid. That pyramid could be divided into two halves, top to bottom, containing General and Special Revelation. General Revelation is “common grace,” described in Romans 1-3 as an intuitive awareness of God, His attributes, and the Moral structure of the universe. This “awareness” makes Man “without excuse” (Rom. 1:20). Special Revelation, however, is a more specific, refined, understanding of God and the Universe. It involves the revelation of Scripture, an awareness of our own guilt before God, a basic understanding of His plan of salvation, repentance, faith, etc. The idea being that Special Revelation builds upon General Revelation.

From my perspective, Christian writers should write across the spectrum. We should be appealing to General Revelation, sowing seeds into ground that the Holy Spirit is tilling, and providing glimpses of Special Revelation. Readers without an explicitly “Christian” worldview should be able to engage our stories and catch glimpses of the biblical scaffolding.

Whole bunches of things can exist inside biblical worldview stories — violence, sex, injustice, death, depravity, and, yes, cussing — just as they actually exist within our world (the reality Christians see as framed in Scripture). Many non-Christians hold to a biblical worldview. Whether it is from an upbringing under Judeo-Christian influence or just intuition, they believe in a God, an Afterlife, and an Absolute Morality by which they will be judged. However, holding to a biblical worldview does NOT prevent one from being immoral and ungodly. Heck, the devil adheres to a biblical worldview… and remains the devil! He believes in God and trembles. In this sense, a biblical worldview story can contain profanity because the real world, the biblical world, contains profanity, evil, and all manner of things we disapprove of. Cussing, killing, and adultery does not make a worldview any less “biblical.”

Christian Fiction, on the other hand, is framed by specific boundaries. While it exists within a biblical worldview, it only represents a cubicle within that world. Strictures such as no profanity, no graphic sex, no zombies, or explicit redemptive themes, are unique to the genre. They do not, however, necessarily frame a biblical worldview. CBA guidelines are far more evidence of a specific theology than they are necessarily representative of the larger biblical worldview. Much like a religious denomination emphasizes certain doctrinal distinctives (baptism, communion, eschatology, spiritual gifts, etc.) while sharing biblical “essentials” (see: Nicene Creed, Apostles Creed, etc.) with the larger Church, CBA fiction is more like a denomination within the larger Body of fiction writers / readers. It shares their worldview, but chooses to emphasize specific distinctives. So while all Christian Fiction should contain a biblical worldview, not all Biblical Worldview Fiction will be recognized as CBA-style Christian Fiction.

So that’s my going theory. I’d love your suggestions and input. Am I missing something here? Do you think Biblical worldview fiction is the same as Christian fiction? Or should we be careful not to conflate the two? Thanks for reading!

Good post, Mike. One think I’ve learned in a lifetime of reading, and particularly in the last 20 years, is that a Biblical worldview can even be found in a lot of general fiction, even if the Bible and Christ are not mentioned once. The novels of Wendell Berry, Marilynne Robinson and Kent Haruf are a few examples. Even the NYT bestselling “All the Light We Cannot See” by Anthony Doerr contains themes of redemption and sacrifice that reflect a Biblical worldview.

Exactly, Glynn. Which is why I tend to see Christian content as existing on a continuum rather than in a box. Stories can have more or less Christian content, but drawing stark lines and pronouncing something “not Christian” — like CBA readers do with profanity — if it crosses a line, is a mistake.

“Many non-Christians hold to a biblical worldview. Whether it is from an upbringing under Judeo-Christian influence or just intuition, they believe in a God, an Afterlife, and an Absolute Morality by which they will be judged.”

Very well said, Mike. Expresses what I’ve been thinking for a while. For now, it comes back to knowing your audience – there are readers who have been trained to read only stories without swearing, sex, etc., and I don’t believe they will change their minds any time soon. Others have no problem with such things included in fiction. I agree with your closing statement “while all Christian Fiction should contain a biblical worldview, not all Biblical Worldview Fiction will be recognized as CBA-style Christian Fiction.” It is rather like a denomination.

So when writing, we should keep those factors in mind: is my story going to appeal only to the denomination? Or will it appeal to a broader audience?

I agree entirely. The disconnect between what gets called “Christian fiction” and what’s actually in the Bible has long bothered me.

For example, Judges and Song of Solomon are respectively more horrific and more explicit than would be accepted in a “Christian fiction” title. A common explanation for the disconnect is that those actually happened, but fiction illustrates reality, so that’s actually support for putting such features in, not against it.

That said, I have a set of novellas coming out next week where the files include both an original and a “clean” edition, trimming the cussing and sometimes crass language. The original edition does a better job of portraying the themes, but the “authorized cut” still works fine, so I figured it didn’t hurt to produce both versions, for the sake of readers who want to avoid those words.

Something clicked for me here… the analogy of CBA and those writers/readers who adhere to their standards as gospel being their own denomination of Christiandom. That may very well change the way I process/deal with criticism from that camp. I do wonder though what the ‘industry professional’s’ take is on a good chunk of the individuals at Realm Makers, and the conference itself… is there a difference to them between CBA guidelines of what constitutes acceptable and their personal take on the matter as a reader?

Good question. We talked for about a half hour. My sense is that they made no distinction b/w CBA guidelines and what they viewed as biblically tolerable. For example, they mentioned that they never watch R-rated movies.

I have to be so careful with that sort of individual/viewpoint. My gut reaction is to write off anything they might have to say due to what I consider a faulty/lazy logical thought process (and bad theology)… but then I also want to be sensitive to the fact that for that individual their conscience might dictate to them that those are important standards that they need to keep. I’m not in a position of authority to judge what is in their heart or how the spirit is working in their life. *BUT* it is really difficult to not toss all of that persons insights aside when their view implies that the use of my talents is displeasing to God because it doesn’t fit their framework. What your denomination analogy did for me was put a buffer between the personal pain I feel when rejected and the offender. They are not trying to belittle me, their denomination just peddles some bad theology, but we still all have our faith in the important things so agree to disagree and move on as friends (for my part).

As long time reader and as a Pastor I have long felt the way you do on Christian fiction with an apparent worldview, which has its place – in fact my wife loves that. I have always read outside of the box. As a young Christian and as an older Christian I was raised in the writings of Tolkien and Lewis than went on to L’Engle and Baum and back again. I branched into Stephen King and Dean Koontz (whom I read can be described as the most widely written fiction with a Christian worldview. ) I have continued on into yours and Ted Dekker and Peretti etc. I see that Veronica Roth who calls herself a Christian also wrote in a subtle way her faith into the Divergent series. In fact, Speculative fiction often I think is a kind of outreach to an audience who might never read say the Left behind series etc. I know that reading Frankenstein and Tolkien and Lewis and even The Omen books encouraged me to ask is there more out there beyond myself as far as meaning and purpose. L’Engle also was big sign post and coming to realize with a struggling Catholic faith that there was indeed a war between Real Good and real evil beyond the physical world.

I think you hit the nail right on the head. I have a manuscript for a novel about Christians persecuted in ancient Rome. It has some affinities with CBA Christian Fiction, but it does not fit their mold. It has sex because Rome was a seedy culture and guess what? Christians do have sex. It has profanity (mostly in Latin) because some of the characters are rough, particularly in a gladiators’ school or prison. It has violence because of the Arena and everything that surrounds it. And surprise, folks, the Bible has all that too. You don’t think there’s graphic violence in the Bible? Read the death of Jezebel. Even Game of Thrones doesn’t have anything that brutal. You don’t think there’s explicit descriptions of sex in the Bible? Song of Solomon, Adam and Eve, David and Bathsheba. If the Christian Fiction genre doesn’t want to take that on, that’s fine. But there should be a proper term for fiction with Christian (or Jewish) themes and values that can talk about real life as honestly as the Bible does. I’m trying to claim the term Biblical Fiction for that purpose, so I’m already on board.

I’ve been aware of this for years. In my family it’s known as “stealth-Christian”–books written by people of some kind of faith whose faith leaks into their work. For instance, Jim Butcher’s Catholic upbringing (I think) shows through in his Dresden books quite a lot. Look at the conversation Harry has with Lash about free will. Or the lecture that Michael gives everybody in Skin Game about a father’s love for his children. Same with the gal who wrote the Guardians of Ga’Hoole. Not sure what her worldview is, but in her first book, the owls proudly talk about knowing a Psalm.

I think the general market is a much better crucible for defining one’s faith than the CBA. Hit the necessary tropes and theology points, and people will love you, no matter how insipid the story.

Some parts of the Bible itself seem to me not to be written from a “biblical worldview.”

For example, book of Esther. Not just in the lack of a mention of divine intervention, but also in how it mutes the pain and violence towards women in the story. Ditto for the Book of Judges. And the end of the Book of Nehemiah, and parts of Ezra. Even 1st Corinthians and Romans. God has a much deeper and wider worldview and considers much more, than the perspective adopted by the tellers of the stories in those books.

Weird conundrum, huh? For the Word of God.

Thanks for articulating this. It has really helped me understand some things in relation to how Australian Christian Fiction writers seem to be falling foul of the US CBA. I had not quite seen it how you described the smaller square like a denomination within the whole, but that makes perfect sense, and I can now say I write with a Biblical world view.

I like your perspective and want it to be correct, perhaps because it validates my reading habits, as well as the subjects, style and themes I am drawn to as a writer. I’ve used the distinction between general and specific grace in my classes too, primarily to argue that we fail to do justice to God’s general grace when we dismiss a good book entirely simply because we find some of its elements objectionable.

That said, I do wonder if you are not using the term “biblical worldview” too freely. I don’t think that a non-Christian can have a biblical worldview. For me, worldview means a comprehensive way of looking at and understanding the world, including the moral realm. Your worldview will determine how you answer questions such as: What is best in life? How should we live? What, if anything, is worth dying for? You suggest that Satan’s worldview might be called biblical (with a nod to James’ epistle), but clearly he would have different answers to the above questions than a Christian would. I think the confusion might slip in when one fails to acknowledge that views on ethics and morality are a necessary part of any worldview. The part of the devil’s worldview that relates to strict, non-moral ontology might be called biblical, but the part of his worldview that underlies his moral attitudes cannot be called so. While I grant that many non-Christian (and even anti-Christian) writers unconsciously owe much of their intellectual and moral underpinnings to Christianity or Christendom, that does not make their worldview Christian. It just makes their worldview inconsistent.

A reverence for truth ought to accompany the Christian worldview, and when a writer purposely misrepresents the world (e.g. by pretending that it has no cussing or adultery in it) he is in fact propagating a lie, and so fails his artistic duty to present a truthful account of the world. Christian authors who do not shy away from representing sins as they exist in the world should still carefully consider with what attitude they represent sin, it should not be gratuitous, or (this is tougher) apparently condoned. A worldview is not just a view of the world as it is, but also is vision of what the world ought to be.