One of the most recent theatrical trailers for Ridley Scott’s Alien: Covenant includes this ominous tagline: “The path to paradise begins in hell.” In an an article at ScreenRant entitled “Alien: Covenant Tackles Science and Religion,” the author notes:

One of the most recent theatrical trailers for Ridley Scott’s Alien: Covenant includes this ominous tagline: “The path to paradise begins in hell.” In an an article at ScreenRant entitled “Alien: Covenant Tackles Science and Religion,” the author notes:

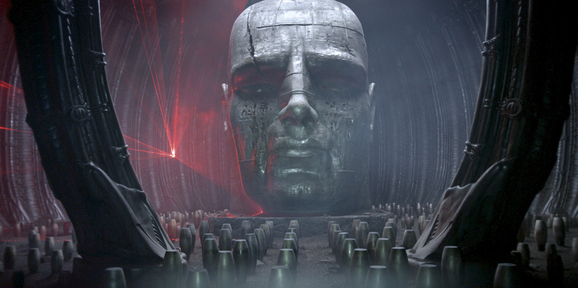

That Covenant will be exploring themes of religious beliefs and faith has been clear for some time, going back to when the movie was originally titled Alien: Paradise Lost (as a reference to John Milton’s Biblical poem, Paradise Lost).

But the film’s (and the series’) religious parallels and references don’t stop there. In fact, the religious themes are so prolific that the folks at Movie Pilot were led to ask, Are ‘Alien: Covenant’ & ‘Prometheus’ Religious Propaganda?

The recent Alien prequels have taken the classic sci-fi franchise in a very different direction to the originals, introducing a plethora of new concepts and themes. One of the most recurring and surprising addition to this backstory is the high amount of religious references.

What makes this so surprising is the fact that director and writer Ridley Scott is a staunch atheist. In an interview with Collider, he once said that “one of the biggest problems in the world is the word we call religion. That creates more problems than anything else in the goddamn universe.”

And yet despite his stance on religion, he still includes an inordinate amount of religious metaphors in his films.

It’s interesting that a “staunch atheist” would be so drawn to religious themes. Or is it?

The truth is, while many science fiction writers and readers share Scott’s atheism, or some softer version of agnosticism, the genre appears to keep coming back to religious ideas, images, and questions.

In an older post over at the Tor website, Teresa Jusino explores the same overlap. Her post, Religion and Science Fiction: Asking the Right Questions, notes the proliferation of religious themes in sci-fi. Not only does she not have a problem with it, she thinks it’s quite normal for us to go there.

What all of these stories do well with regard to religion (with the exception of The Phantom Menace, which did nothing well) is capture what I think the discussion should really be about. Most people who debate science vs. religion tend to ask the same boring question. Does God exist? Yawn. However, the question in all of these stories is never “Do these beings really exist?” The question is “What do we call them?” It’s never “Does this force actually exist?” It’s, “What do we call it?” Or “How do we treat it?” Or “How do we interact with it?” One of the many things that fascinates me about these stories is that the thing, whatever it is—a being, a force—always exists. Some choose to acknowledge it via gratitude, giving it a place of honor, organizing their lives around it and allowing it to feed them spiritually. Others simply use it as a thing, a tool, taking from it what they will when they will then calling it a day. But neither reaction negates the existence of the thing.

Good science fiction doesn’t concern itself with “Does God exist?”, but rather “What is God?” How do we define God? Is God one being that created us? Is God a race of sentient alien beings that see all of time and space at once and is helping us evolve in ways we are too small to understand? Is God never-ending energy that is of itself? And why is it so important to human beings to define God at all? To express gratitude to whatever God is? Why do people have the need to say “thank you” to something they can’t see and will probably never understand? To me, these are the important questions. They’re also the most interesting. (emphasis mine)

I think Ms. Jusino’s angle is a good one. The question is not whether God exists, but what is he/it like. In fact, this appears to be the trajectory of Scott’s Alien series — to address the issue of origins. However, conceding the existence of God or some Super Intelligence (or in the Prometheus world, the Engineers), is precisely what hangs up many hardcore proponents of science fiction.

For example, take the following comment on the aforementioned post (#22):

As to science and religion being complementary, though, I have to say I disagree. Critical thinking and rigorous standards of evidence are at the core of science. Religion seems to be at the opposite end of the spectrum–employing the weakest conceivable criteria and standards of evidence.

I think that’s why so many of us who are interested in science come to be nontheist even when, as in my case, they were raised religious. To believe religious claims requires that one set the bar artificially low. As one commenter noted, this didn’t have to be the case. In so many of the science fictional worlds described there is clear evidence for the supernatural forces and being at work in the world.

In the actual world though we have to settle for rather weak philosophical arguments, miracle claims that never seem to be verifiable, claims of prophetic foreknowledge about as dubious as the latest newspaper psychic’s predictions for the new year, and, most of all, “I just feel it in my heart” (and here we hear the bar hit the ground with a resounding thud).

Is it any wonder that so many who are scientifically literate are nonreligious? (bold mine)

So while many accept that a hunger for God (or Something numinous) is fundamental to human nature, hardcore materialists refuse to go there. And as many science fiction fans are devotees of Science (see: scientific materialism), it is only natural that they tolerate the “God question” only insofar as it is answered in accordance with scientific literacy.

Of course, this didn’t stop one reviewer (who happens to call himself a chaos magician) from seeing the films as channeling a “gnostic creation myth“:

Prometheus really is a gnostic creation myth and the deliberate – sometimes clunky – injection of physical AAT [Ancient Astronaut Theory] into a Biblical creation arc designed to make those who have eyes to see really sit up and notice. Scott’s not just sprinkling some churchiness on top of a monster movie.

…This is a nested gnostic tale. It is a Luciferian story nested in the ‘Alien Bible’ universe that Prometheus describes. It also does a bang-up job of exploring the anger in the Lucifer form and has some detailed meditations on the notion of creation and justice that really surprised me after the on-the-nose opening sequence. Whilst it can come close to the fruity, Theosophical Luciferianism of the nineteenth century and the Romantics that preceded them -“but if God bad then me think Lucifer… good?”- Covenant manages to pull back at just the right moment to avoid that fate.

And herein lies sci-fi’s “God problem.”

On one hand, to concede the premise that God, or something like God, may exist, is to undermine the entire atheistic presupposition of so much science. It’s the same reason why the above commenter suggested that “so many who are scientifically literate are nonreligious.” It’s not because there isn’t evidence for an Engineer, but because by conceding the possibility of an Engineer, scientists get a step closer to conceding the possibility of a Super-Intelligence, a Creator, and ultimately the Judeo-Christian God. And this is the big no-no.

On the other hand, there’s the “gnostic creation myth,” the “Luciferian story nested in the ‘Alien Bible’ universe” theory. How far such an esoteric theory goes in satisfying the “God question” is another story. No doubt, hardcore sci-fi fans will see any connection to Luciferian archetypes as far too “religious” to deem a plausible resolution and not nearly “scientifically literate” enough. However, such a nebulous interpretation at least steers clear of anything remotely biblically sound… which is the ultimate objective of “true” devotees of Science.

I think Scott’s motives are clear. If I were to summarize in (my imitation of) his thought process, it’d be like this: “Ok, let’s say for sake of argument that the defense of Intelligent Design has some basis in reality. So what? Even if I concede design happened, that doesn’t mean the designer(s) was in any way good or worthy of our worship.”

Scott’s latest alien films are intended to be an attack on religion, specifically the idea that God is good. And I do not feel Scott is abandoning his atheism in the slightest.

Having just seen Alien Covenant this last weekend, I have to say that I agree with Travis 100%. Scott is really pushing his atheist agenda and it no where more clear than when the most sniveling, unheroic character on the ship refers to himself as “Man of Faith.” This character, and all the other theatrical contortions aimed at attacking religion in general really hurt what could have been a good movie. I left disappointed.

Athiests and Believers all have faith in something modern science cannot unequivocally verify. The difference is upon what or whom this faith is placed. It is easy for someone to claim that science and belief in a God are incompatible when they will not admit their own inherent bias. In Jesus’s day, the crowds pressured him for more miracles, saying “then we will believe.” The existing evidence was never enough. Jesus knew their disbelief was due to their hearts, not lack of evidence.

In some cases, I think the assumption of a God in science fiction is not to legitimize its discussion but to discredit it along the lines of little green men and face hugging xenomorphs – fun ideas to kick around but never seriously consider.