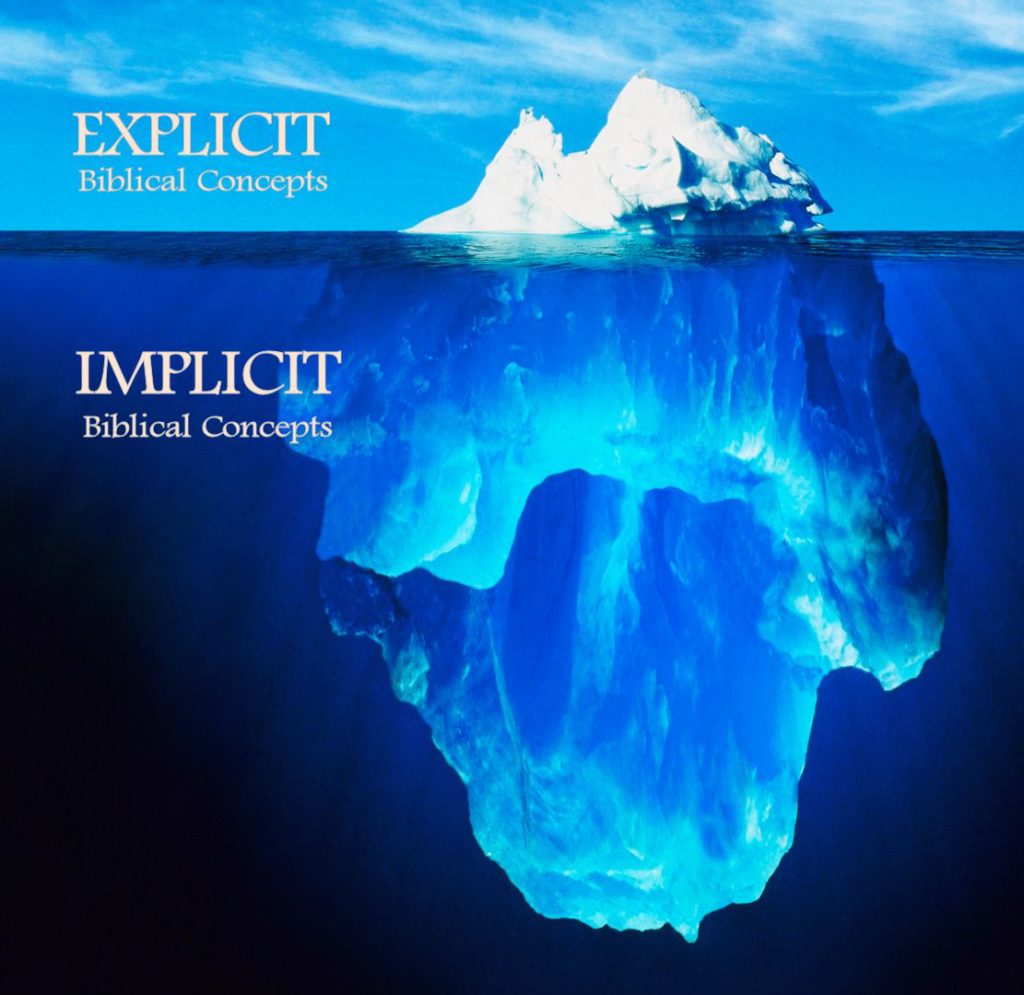

Tip of the Iceberg — Image by © Ralph A. Clevenger/CORBIS

Later this week, I’ll be teaching a class at a writers conference entitled “Writing for the General Market.” This is a Christian writers conference, thus the emphasis on the general market as opposed to the “Christian” market. When I officially began pursuing a career as a writer back in 2003 /04, the Christian market was the default market Christian novelists were aiming at. At that time, Christian fiction was thriving. Combine that with oft-stated objections to “secular content” and a rather narrow interpretation of evangelistic methodology (I’ll get to this in a second), and you had a fairly saturated market.

Over a decade later, things have changed significantly. Part of this is due to changes in the publishing landscape. Another part, at least among Christian authors, is a growing (perhaps “maturing” is a better word) understanding of what art and cultural engagement can look like. Either way, more and more Christian writers are now seeking to branch into the general market.

I recently discovered a good example of this developing perspective in professor Holly Ordway’s new book, “Apologetics and the Christian Imagination.” Early on in the book, Ordway establishes that one component of apologetics involves “creating meaning,” bringing life to foundational concepts intrinsic to salvific belief which may be misunderstood by the hearers (concepts like sin, redemption, faith in God, etc., etc.). However doing this  requires we approach apologetics as “a spectrum of engagement.” Some of this involves appealing to Reason, others involves appealing to Imagination.

requires we approach apologetics as “a spectrum of engagement.” Some of this involves appealing to Reason, others involves appealing to Imagination.

Reason and Imagination are twin faculties, both part of human nature–and both given to us by God our Creator!–that, together, allow for a further grasp of the truth.

In this sense, effective apologetics must not simply appeal to linear thought but to abstract thought as well. Ordway uses C.S. Lewis (and herself) to describe what she calls “a two-step conversion.” The first step in Lewis’ conversion was “a conversion to Theism, not to Christianity.” He moved from strict atheism to a belief in God. It was an inability to grasp certain doctrinal issues, namely the Atonement, that prevented Lewis from taking the next step and embracing Christianity. This changed when Lewis’ Imagination was engaged. Specifically his love for myth and how Christ was “the true Myth” or “Myth become flesh.” Ordway summarizes,

When Lewis realized that he could connect his imaginative response to the story, to the factual reality of the Christian claim about the Crucifixion and Resurrection, the final barrier to belief fell. He could become a Christian as a whole person, with both his imagination and his reason fully engaged.

This is an important point for Christian novelists. Too often we see our work as not “Christian” enough unless it appeals to Reason and clearly articulates some element of the Gospel. Another way to view this could be in terms of Implicit and Explicit Christian content. Many believers have been conditioned to define a novel’s Christian-ness in terms of explicit content — overt Scripture references, Christian characters, some form of Gospel proclamation, a redemptive movement, etc. However, what we often fail to recognize is this:

Implicit biblical ideas form the foundation of more explicit biblical beliefs.

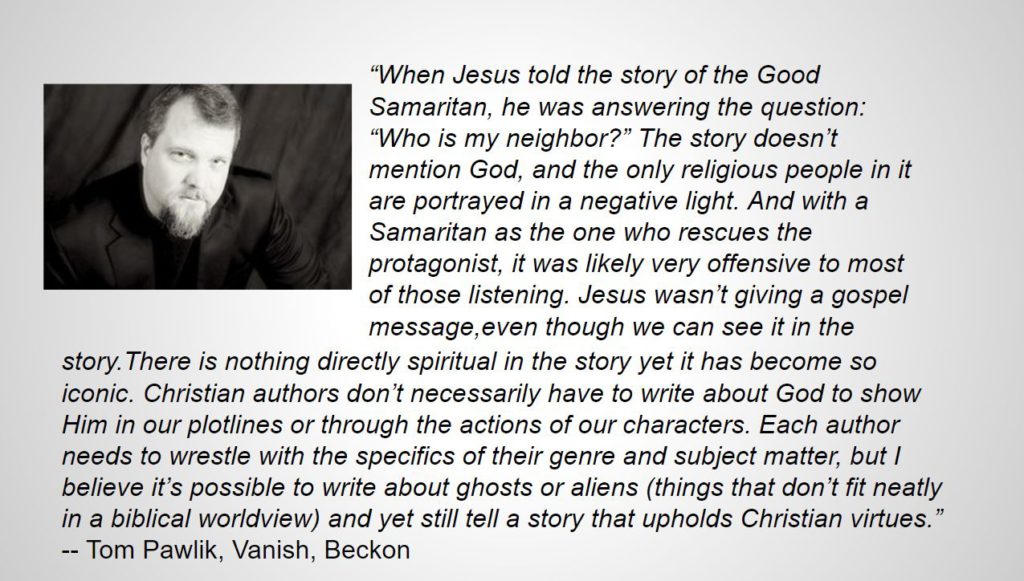

To tease this out, here’s one of the slides I’ll be using in my class. It’s a quote from Tom Pawlik, a popular Christian author, from an interview I conducted with him. We were discussing what exactly constitutes “Christian content” in a novel.

Pawlik rightly notes how the story of the Good Samaritan, though containing no explicit references to God or the Gospel, “upholds Christian virtues.” So a listener or reader of the Good Samaritan, without having explicit knowledge of the Gospel, can still engage with its implicit biblical concepts. The idea of intrinsic human worth, transcending structures of class and race, and sacrificing ourselves for the good of others are intrinsic to a biblical worldview. Once extrapolated to their fullness, they speak to explicit Christian concepts concerning the nature of human beings, the societal and individual repercussions of sin, and the risks and rewards of redemption.

And this brings us back to Ordway’s idea of a “two-step conversion.” In the same way that Lewis moved incrementally from atheism to theism, people usually move from implicit to explicit Christian beliefs. Before one can embrace a specific doctrinal distinctive — like the Atonement, the Trinity, the Deity of Christ, etc. — one must at least be a Theist. But the path from atheism or agnosticism to Theism is often incremental. We simply cannot expect someone to embrace explicit biblical concepts without first embracing foundational implicit concepts. Part of the “spectrum of engagement,” at least from a novelist’s point of view, is to engage a story’s abstract, implicit, and Imaginative components. Using fiction (and giving permission for Christian creatives) to engage the Imagination rather than the Reason is an important step to more powerfully engaging a mainstream audience and seeding the Gospel in culture. While a work of fiction may not explicitly articulate the Gospel, it can still contain implicit elements which engage a person’s imagination and move them forward in their spiritual pilgrimage.

Point being: Writing for the general market and engaging mainstream audiences means being able to see below the “tip of the iceberg” and affirm the much larger body of principles and beliefs which support a biblical worldview.

Thanks for this article, Mike. I think that some Christian writers don’t write more implicit Christian content because they don’t want to be accused of “watering down the gospel” or of somehow being ashamed of the gospel. But some Christians can be very judgmental. I don’t want to use the swear word example to take this discussion down a detour, but the pushback you’ve gotten from your Facebook posts about using swear words is an apt example. Referring to Christian writers who use swear words in their books, one commenter put quotes around Christian (as in, “Christian” writers), as if to question their salvation. (In the same post, this person happened to mention their many, many book sales. I was tempted to ask if bragging and pride were more acceptable sins than swearing, but I refrained.)

Back to the point of your article. In regards to writing implicit content (not just writing but in the arts in general) Christians could learn a lot from Mormons. There are wildly successful Youtubers (such as Lindsey Sterling and The Piano Guys) who are very unashamed about being Mormons yet produce secular content that doesn’t contradict their faith. On the literary side, I think of Orson Scott Card and (begrudgingly) Stephenie Meyer. I can’t help but wonder how many people who may have been open to Christianity converted to Mormonism instead because of theses artists.

Could not agree with you or Mr. Pawlik more. I’m currently penning a novella involving nasty Persian demons…the 12-year-old protagonist hails from a proud atheistic family, yet by story’s conclusion, the God Who is there will have used such spiritual interchanges to reveal Himself.

Really good post, and as I think you know I agree. I wish this were more widely understood among believers, though, because in my experience one of the biggest discouragements for Christian authors who writing fiction for the general market comes from Christian readers who deem the books insufficiently moral by their own particular and sometimes idiosyncratic standards. I’ve had the legitimacy of my faith questioned (for reasons that are still mysterious to me, as the reviewer didn’t actually specify what it was that offended her), and also been told that my children’s books have too much “mature content” to be appropriate for young readers (such as a thwarted suicide attempt by one character).

If readers don’t know that the author of a particular book is a believer, they are often pleasantly surprised and impressed to find any worthwhile spiritual content in the story at all, and will praise it to the skies as a result (see the many excellent articles by Christians about Megan Whalen Turner’s Attolia books, for instance). But as soon as they find out the author is a Christian, their expectations of what will and won’t appear in the book change dramatically. Even if the story reflects Biblical themes and principles, they squirm over the absence of a clear gospel / salvation narrative, or an explicitly identified Christian character who is godly enough to serve as a role model. Content that would amaze and delight them coming from a non-Christian author seems weak and ineffectual to them coming from a Christian one, and they are unlikely to endorse the book or recommend it to fellow believers as a result.

I don’t know an easy answer to this. I suspect most of the people who are reading this blog already agree with the points you’re making about the worth of implicit content — the trick is reaching the readers who haven’t thought about the subject in this way. Hopefully your talk at the conference will help spread the message.

While Evangelical authors sometimes feel pressured to put in explicit Christian content such as a salvation message, Catholic faith-based authors often feel pressured NOT to be like ‘those darn Evangelicals’ and thus have a lot of symbolic and hidden faith content. As a person with a non-subtle mind, sometimes I feel the need for a hint of something explicit and openly Christian in a book so ‘intrinsic’ that I can’t find the Christian message without a map.

But at any rate this article, as usual, has given me much to think about.

At the risk of creating an echo chamber here in the comments: Yes.

If imagination weren’t important to our spiritual selves, we wouldn’t have it in the first place. Part of being made in the image of a Creator is the ability to create. Story is not just valuable, it’s critical to our comprehension and understanding of complex topics.

Implicit truth is no less true; truth is truth, by definition, and it doesn’t matter what wallpaper you slap on it. 🙂 We should be less concerned with labels and niche approval, and more concerned with truth.

During the explosive growth of Christian music, these same issues were always at the forefront. They still are to some extent, but Christian musicians have largely stayed explicitly Christian. However, there is a significant segment that has established itself beyond any “Christian” label — more so than writers. I was reminded of all this recently when reading the comments of Christian singer Lacey Strum. Strum (while fronting the band Flyleaf), said this:

“Well, you know what? I don’t know what you mean by a “Christian rock band.” It’s hard to say that because people all have a different definition of what that means. If it means that we’re Christians, then yeah, we’re Christians, but if a plumber’s a Christian, does that make him a “Christian plumber?” I mean we’re not playing for Christians. We’re just playing honestly and that’s going to come out.”

So like most musicians, Strum wasn’t playing for any specific demographic. However, like all musicians, she obviously has beliefs that influence her work. This approach, the implicit approach, seems to me the more natural and unforced approach to art (whether music or writing).

The difficulty I’ve encountered in writing fiction without explicit gospel content in some form (even allegory, which one could say is what parables are) is that it seems to only reinforce people’s already-held notion that God and His salvation for us aren’t at all necessary. After all, the people in these stories do just fine without all of that; there’s beauty, forgiveness, redemption, and altruism without the need to complicate it with religion–who needs the Father, much less His Son? I ran so hard into that wall through seven years and more of avid writing, that it gradually killed my muse and I just can’t revive it. It just seems that readers get out of an imaginitive, non-explicitly-Christian story only what they bring to it. Hence the huge atheist and non-Christian theist fandom for Lord of the Rings, though those of us who are already Christians can see Tolkien’s faith shining so brightly in it.

Jess – I get where you’re coming from. It’s one of my biggest fears of what will happen when I finally have a book written well enough to release for public consumption. I would find it enormously disappointing if people missed the deeper meanings in what I wrote, but people do the exact same thing (taking away what they want from text and missing the deeper truth) with the Bible, including Jesus’ own words. So, if you have a story to tell, let it out. You can’t control how people will interpret it, but if you’re doing your best to follow what God has given you to do, I have to trust that He will use the work for His purposes.

I don’t have a problem with a lack of explicit content being worked in. However, I have been criticized for having ANY explicit content. I think we are being so clever with the implicit side that we are removing all the punch from our stories. In fact, I wish I could find some that were more like my Lucid Series You have to wonder how being that clever benefits the Kingdom of God.