There’s no shortage of hatred for Halloween. Mainly from well-meaning religious folks.

There’s no shortage of hatred for Halloween. Mainly from well-meaning religious folks.

- “Halloween is the devil’s holiday!”

- “Witches, vampires, and ghosts are not of God!”

- “Have no fellowship with the works of darkness, but rather rebuke them!”

Those were sentiments I voiced at one time or another. We were the parents who turned the porch light off, did not give out candy to trick-or-treaters, and refused to let our kids dress up. I saw Halloween, at best, as a waste of time and money. At worst, it was a culturally sanctioned celebration of all that is Dark, Evil, and anti-Christ.

So what changed my mind?

First let me be clear about my position: Like Christmas and Easter, Halloween is a mish-mash of pagan, religious, and pop-cultural elements; while some participate in Halloween with evil, occult, or godless intentions, the majority of American celebrants participate innocently (or ignorantly, you could say), with little to no actual commitment to some nefarious intent. For many, the 21st century Americanized version of Halloween is basically national dress-up day. Provided that ones’ participation does not constitute celebrating evil, the occult, or obvious sin, Christians are free to follow their consciences in celebrating the holiday.

I began to change my thinking on Halloween through a combination of doing research (on both Halloween and the horror genre), familiarizing myself with the biblical arguments pro and con, and jettisoning a legalistic outlook on life.

Like many of our national holidays, the origins and “meaning” of Halloween are buried under layers of historical amnesia, cultural change, and hollow symbolism. The first Halloween had very little in common with our 21st century version.

The Celtic festival called Samhain (pronounced SOW-in or SOW-an), which means “summer’s end,” is considered the earliest traceable origins of what we now call Halloween. Samhain (a derivation of Saman, the Lord of Death) marked the death of summer and the beginning of winter. This was considered a night of magic and power, where spirits roamed and demons cavorted. To herald this seasonal/spiritual transition, the living would often sacrifice crops and dress in ghoulish costumes so the dead spirits would mistake them for their own and pass by without incident. Masked villagers would sometimes even form parades to lead the spirits outside of town. Food and treats were offered to Saman to curry favor and appease his wrath, as well as to deceased ancestors who were traveling to the afterlife and needed a brief respite.

A collision between Christian missionaries to Ireland and this old world paganism changed everything.

Rather than completely dismantling a religion, the Church often sought to merge some of its beliefs and practices with their own. All Saints’ Day—a time designated on the Christian calendar to honor all dead saints and martyrs—was moved to November 1st. This was intended to substitute for Samhain. Though pagan belief in supernatural creatures persisted, as did their traditional gods, a synthesized form of the celebration soon emerged. Traditional Celtic deities diminished in status, becoming fairies or leprechauns, sometimes devils, and were often joined by Christian characters like angels and miracle-working saints. Sometimes fantastical, absurd renditions of Satan could even be found at the festivities.

Nevertheless, the old beliefs associated with Samhain never really completely died out. People continued to celebrate All Hallows Eve (the evening before All Saints’ Day) as a time of the wandering dead, where spiritual beings roamed. Folk continued to appease those spirits (and their costumed impersonators) by setting out food and drink. Eventually, All Hallows Eve became Hallow Evening, and then Hallowe’en.

As immigrants flooded America’s shores, they brought various beliefs and customs with them. Soon a distinctly American version of Halloween began to emerge. In rural America, ChapelValley.com were often held to celebrate the harvest.

Neighbors would share ghost stories, tell each other’s fortunes, and engage in mischief-making. By the middle of the nineteenth century, annual autumn festivities were common.

That changed in the second half of the nineteenth century when America was flooded with new immigrants.

These newcomers culled Irish and English traditions, began to dress up in costumes and go house to house asking for food or money, a practice that eventually became today’s tradition of “trick-or-treat.”

It wasn’t long before Satan and his minions, as well as Saman the Lord of Death, were stripped of their power.

Whereas the original Fall festivals were decidedly spiritual, their American iterations discarded the saints and devils for family and frolic. By the early 1900s, the holiday had morphed into community and neighborly get-togethers involving games, seasonal foods, and costumes. Halloween eventually lost most of its superstitious and religious overtones and become a secular, but community-centered holiday featuring parades and parties. But by the 1950s, Halloween had evolved into a holiday mainly for the young. This coincided with the baby boom and eventually the centuries-old practice of pumpkin carving and trick-or-treating was revived. American consumer culture took advantage and it wasn’t long before cheap plastic masks and costumes of cowboys, princesses, devils, and angels were being mass produced for the kiddies. Halloween had gone mainstream.

Of course, some churches were busy branding Halloween as Satan’s Holiday. Earnest ministers condemned the celebration as the most important day on the witches’ calendar, and claimed the holiday was covertly intended to domesticate the occult. Rather than fearing the devil, they argued, we have trivialized him. However, for most Americans, Halloween’s religious elements had long ago been stripped away. Saman, the Lord of Death, as well as All Souls Day, had been overshadowed by another god—the god of consumerism.

Of course, some churches were busy branding Halloween as Satan’s Holiday. Earnest ministers condemned the celebration as the most important day on the witches’ calendar, and claimed the holiday was covertly intended to domesticate the occult. Rather than fearing the devil, they argued, we have trivialized him. However, for most Americans, Halloween’s religious elements had long ago been stripped away. Saman, the Lord of Death, as well as All Souls Day, had been overshadowed by another god—the god of consumerism.

Last year alone (2016) Halloween retail spending reached a record high in the U.S. at 8.4 billion dollars. Other records were broken, including the number of those celebrating (171 million) and how much was spent per participant on costumes and candy ($82.93). Halloween is typically ranked as one of the most popular holidays on record, sometimes surpassing Easter, Thanksgiving, and Mother’s Day. Americans now spend more money on Halloween than any other holiday except Christmas.

The popularity of Halloween has grown in direct proportion to the rise of pop culture. Now it is not uncommon to find Halloween costumes and images melded with both the creepy and the comedic. Whether it’s costumed witches, clowns, anime characters, or superheroes, you’ll likely find some iteration of them on October 31st. Halloween has become a barometer of our culture’s latest villains or box office hits. It is a time to mock political figures, lampoon celebrities, emulate icons, and affirm current trends. From dinosaurs to zombies, robots to slashers, you are sure to find some sampling of the weird and wacky.

Halloween has thrived, but only as it has shed its somber religious roots in favor of fun, festivity, revelry, and lots of sweets.

Understanding the history and the cultural synthesis of the holiday helped me to see it in perspective. Even more important was acknowledging the fact that vestiges of paganism can be found embedded in many of our most sacred holidays and strewn throughout our national life. For example:

- Christmas was the Winter Solstice

- Easter was Ostara (the Spring Equinox)

- Halloween was Samhain

- Valentine’s Day was Imbolic

- May Day was Beltane

- Tuesday was Tyr’s (Tiw’s) Day

- Wednesday was Woden’s (Odin’s) Day

- Thursday was Thor’s Day

- Friday was Freya’s Day

- Saturday was Saturn’s Day

- Sunday was the sun’s day

So I was faced with the question, Why rail against Halloween when so many other holidays and cultural markers have pagan origins or elements? Truth is, the same people who denounce Halloween often put up a Christmas tree, a wreath, or color Easter eggs… customs that are all pagan in origin. In fact, the very currency we work for and exchange contains possible occult and esoteric symbols. So how does a well-meaning person with a healthy fear of the occult and paganism respond? Must we never celebrate Halloween, color Easter eggs, decorate a Christmas tree with the best glowing accessories from this site, or use paper bills? The answer, for me, was rather simple — I don’t worship my Christmas tree. I also don’t worship or recognize Ostra, Imbolic, Thor, or Saturn. Christians can participate in an event or ceremony that has some pagan origins or attachments without honoring those elements. As such, I can celebrate Halloween without invoking Saman, Satan, or Druidic lore.

Perhaps the most important factor in my change of heart regarding Halloween came from my study of Scripture. You see, a similar debate occurred in the early church that is very instructive in this regard. Many new converts had been saved from paganism and were averse to any vestiges of their former ways of life. For example, they refused to eat meat that was sacrificed to idols believing that it was spiritually corrupted. Others did not share their convictions and had no problem eating this meat. The apostle Paul spoke to this issue in I Corinthians 8. He concluded with three important points:

- Idols are nothing. They have no power over meat. (vs.4)

- “food does not bring us near to God; we are no worse if we do not eat, and no better if we do.” (vs. 8)

- Don’t allow your liberty to stumble someone with a weaker conscience (vs. 9)

Paul follows a similar line of argument when speaking to the Roman Christians. In this case, the church was arguing over not just what food they should or shouldn’t eat, but what special days should or should not be observed. He writes:

Accept the one whose faith is weak, without quarreling over disputable matters. One person’s faith allows them to eat anything, but another, whose faith is weak, eats only vegetables. The one who eats everything must not treat with contempt the one who does not, and the one who does not eat everything must not judge the one who does, for God has accepted them. Who are you to judge someone else’s servant? To their own master, servants stand or fall. And they will stand, for the Lord is able to make them stand.

One person considers one day more sacred than another; another considers every day alike. Each of them should be fully convinced in their own mind. Whoever regards one day as special does so to the Lord. Whoever eats meat does so to the Lord, for they give thanks to God; and whoever abstains does so to the Lord and gives thanks to God. For none of us lives for ourselves alone, and none of us dies for ourselves alone. If we live, we live for the Lord; and if we die, we die for the Lord. So, whether we live or die, we belong to the Lord. For this very reason, Christ died and returned to life so that he might be the Lord of both the dead and the living. (Romans 14:1-9 NIV)

So once again Paul reasons that certain foods or certain days are no more “sacred” than another. Sunday is not intrinsically a “holy” day just as meat sacrificed to idols is not intrinsically unholy. Rather, we should be persuaded by own our consciences and give others the freedom to do the same. Or as Paul puts it, “Each of them should be fully convinced in their own mind” (vs. 5).

Similarly, I’ve come to believe that the celebration of Halloween falls under “disputable matters” (vs.1). There is no clear biblical compulsion for or against celebrating Halloween. Though there are pagan elements of Halloween, there are also deeply religious ones, many of which are celebrated today during All Saints’ Day. Though there are those who use Halloween as an opportunity to revel in evil or venerate something/someone devilish, there are those who use Halloween to celebrate family, community, or their favorite pop-cultural character. Halloween has become too big, too historically convoluted, too commercialized, and too much a part of American culture, to attach one specific verdict or motive. People celebrate Halloween for lots of various reasons, both good and bad.

But there is just nothing inherently evil about dressing up as a pirate for the office party.

Mind you, I’m still not a huge fan of Halloween. I’m just no longer a Scrooge about it. I have no problem taking the grandkids trick-or-treating, decorating my truck up for Trunk-or-Treat, or judging the best costume at the pageant. Sure, I don’t personally dress up. I think the amount of candy consumed by our kids this time of year is insane. And the celebration of gore bothers me. But personally, it’s come down to the realization that I have a tendency to be legalistic, and there’s no compelling reason to believe that anyone who participates in Halloween is somehow a pawn of Satan.

Please understand, I am not trying to persuade anyone to chuck their concerns about the occult or spiritual darkness. As Paul wrote, “Each of [us] should be fully convinced in their own mind.” If you believe that participation in Halloween is somehow evil, then by all means don’t do it. Just please note that there are many aspects of our culture and history that can be traced to pagan origins. Like meat sacrificed to idols, things aren’t inherently unholy just because a druid once touched them.

Whatever your opinion, Halloween is an ever-changing reminder of our spiritual roots and just how far we’ve drifted from them. It’s evolved from a religious / ethnic celebration to a blend of street festival, fright night, and vast commercial enterprise. Drawn from an array of sources as disparate as the classic monsters of Hollywood to pagan harvest festivals, this constantly morphing holiday blends the mystery of life beyond the grave with pop cultural whimsy, forming a bizarre concoction of the somber and the comedic, the saintly and the sinful.

Perhaps the bigger sociological issue, for me, is why people like dressing up, pretending to be something they’re not. And why people like being scared. Which is a subject I’ll explore in my next post.

I just don’t have time to give as full a response as I’d like, which would require explaining there is a child version of Halloween which is pretty innocent and an adult version, which contains a lot of drunkenness and other negative elements and for which I see no cause to celebrate.

Rather than launch into that, let me simply mention while once upon a time there existed a holiday called “Easter” in Northern Europe, which was always linked to the Spring Equinox, it is NOT true that our modern Easter comes from that celebration. The resurrection of Jesus is an original Christian holiday linked to the Passover, which itself was a lunar holiday, not linked to the equinox in any way. (The name for the holiday is even derived from the word for “Passover” in all the non-Germanic languages, e.g. “Pascua” is it’s name in Spanish.) A few Easter customs and even the name of the holiday (in English and a few other languages) was tagged on to the pre-existing Christian celebration as Christendom expanded northwards from the Mediterranean. That’s the exact opposite of the story of Halloween.

Christmas was on the other hand a deliberate gloss over the Pagan holiday of Saturnalia (and later this gloss was also applied to the Northern European holiday, “Yule”). But because of a change in calendars over time, Christmas as celebrated by Western Christians (at least some Eastern Orthodox has a different date for the holiday, in January), is three days later than the Winter Solstice. So the modern Pagans are having their celebration on a separate date from Christmas.

That is not true of Halloween. It still retains the original Pagan date.

Now, you may feel the cases of Christmas and Easter are not significantly different than the case of Halloween. But to maintain their are NO differences, especially in Easter vs. Halloween, would be false.

Just to set that issue straight. 🙂

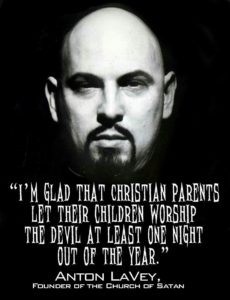

Thanks for the entertaining read. Your facts are certainly correct about pagan roots in religious holidays. I have to disagree, however, having been deeply involved in the occult prior to praying for salvation. There is no comparison between the other holidays you mentioned and Halloween, regardless of their pagan roots. (Thank you for including Anton LaVey’s quote.) Regardless of how innocently the typical citizen celebrates Halloween, it remains the satanists’ high holiday, and why would any serious Christian, knowing that, do anything but pray against it?

As someone who grew up in a similar home and has a similar leaning toward legalism, thank you for this post, Mike. Tracing the history of the holiday is super helpful, as well as the understanding that it has progressed being its occult roots. If its focus was still distinctly and primarily spiritual and occult-focused, perhaps it would be different. But I appreciate your summation, “ Provided that ones’ participation does not constitute celebrating evil, the occult, or obvious sin, Christians are free to follow their consciences in celebrating the holiday.”

This is a different topic but the discussion makes me wonder, would you classify Harry Potter the same way? It uses the tropes of witchcraft with a connection to a distinct spiritual power—save for the darkest moments, when it does seem to portray very spiritual rituals (which, I think, are all instances that are portrayed as evil).