Jesus told stories that did not always have a positive or uplifting outcome. Oftentimes, there was ambiguity in their resolve. Sometimes there were images of horror and dread. For example, The Parable of the Rich Man and Lazarus (Lk. 16:19-31) ends with the rich man in a “place of torment,” prevented from returning to warn his brethren. The Parable of the Wheat and the Tares (Matt. 13:24-30) is explained by Jesus (13:36-43) to refer to “children of the wicked one” who will be cast into an eternal “furnace of fire. There will be wailing and gnashing of teeth” (vs. 42). The Parable of the Sheep and the Goats ends similarly bleakly (Matt. 25:31-46), with the unrighteous being banished into “eternal punishment” (vs. 46 NIV).

Jesus was not afraid to scare the hell out of people and use shocking imagery in the process.

Despite all this, much evangelical art and artists eschews images of terror or unease in favor of hope, positivity, and nauseatingly upbeat fare. But in doing so, Christian communicators often neglect the redemptive power that can be found in images and tales of woe.

In a recent podcast interview with the guys at Pop Culture Coram Deo, I shared a bit about my conversion to Christianity. A major step in that process was a shocking realization that evil — more specifically, the Devil — was real. And being that I was steeped in occultism at the time, the evidences of evil were all around me, from Ouija boards to Hindu icons to Satanic symbology. The representations of evil that I’d gathered around me pricked my conscience and became a springboard to repentance. God might have had a wonderful plan for my life, but it was Satan’s plan and his diabolism that set me on the straight and narrow.

Apparently, I’m not the first person to be scared into the Kingdom.

One of the more prominent cases is that of Peter Hitchens, brother of one of the world’s most famous atheists, Christopher. Interestingly enough, Hitchens’ spiritual wake-up call came in the form of a 15th century painting.

In How I found God and peace with my atheist brother, Peter Hitchens chronicled his slide into atheism and back again.

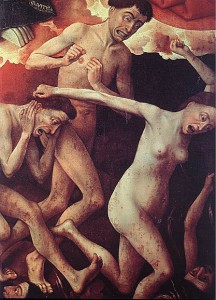

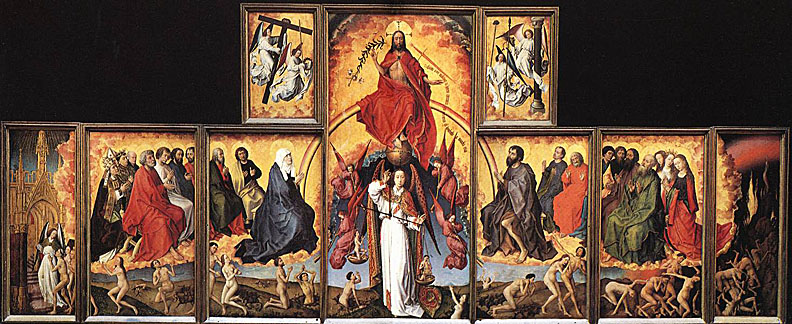

No doubt I should be ashamed to confess that fear played a part in my return to religion, specifically a painting: Rogier van der Weyden’s 15th Century Last Judgement, which I saw in Burgundy while on holiday.

I had scoffed at its mention in the guidebook, but now I gaped, my mouth actually hanging open, at the naked figures fleeing towards the pit of Hell.

These people did not appear remote or from the ancient past; they were my own generation. Because they were naked, they were not imprisoned in their own age by time-bound fashions.

On the contrary, their hair and the set of their faces were entirely in the style of my own time. They were me, and people I knew.

I had a sudden strong sense of religion being a thing of the present day, not imprisoned under thick layers of time. My large catalogue of misdeeds replayed themselves rapidly in my head.

I had absolutely no doubt that I was among the damned, if there were any damned. Van der Weyden was still earning his fee, nearly 500 years after his death.

Of course, there was more to Hitchens’ re-conversion than just an art viewing. Nevertheless, the sense of dread and the conviction that picture evoked is a testament to the power of art. Even after centuries, Van der Weyden “was still earning his fee.” 500 years after his death, his composition still possessed the ability to puncture the mundane, arouse the conscience, and extricate the viewer from their moral malaise.

Perhaps Christian art would be better if we spent a little less time being “painters of light” and more being prophets of woe. After all, Jesus’ stories were not always feel-good paeans of positivity. Sometimes His hearers left feeling, like Hitchens, that they were “among the damned.” In this sense, redemptive art isn’t always about angelic choirs and sparkly Easter morns. Sometimes, only the image of the Rich Man in eternal torment can awaken the soul.

*slow clap*

Great post, Mike. It seems to me that this is definitely a two-sided coin. “Painters of light” can evoke feelings of yearning for that safe, beautiful, heavenly place, while “prophets of doom” invoke the fear of hell. Different folks, at different times of their lives, will be attracted to the one or repulsed by the other.

There’s so much in Christianity that properly (I believe) exists in the tension between two extremes or even two opposites. Believing that God is sovereign over all, and yet believing he has given us freedom of choice. Believing that we should obey and not sin and yet living in the confidence of knowing our sins (all of them: past, present and future) are forgiven.

And yet so many Christians I know tend to embrace one extreme or another without being willing to exist in the discomfort of embracing the paradox. It’s like we desire certainty so much that we’re willing to sacrifice the big picture of truth simply because it doesn’t fit neatly in a box.