Francis Schaeffer coined the phrase “Doing the Lord’s Work, the Lord’s Way” in his book No Little People. In it, he argued that “the central problem of our age” is that “the church of the Lord Jesus Christ, individually or corporately, tend[s] to do the Lord’s work in the power of the flesh rather than of the Spirit.” (p. 66).

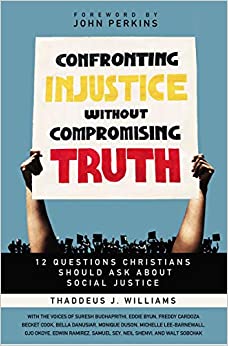

The problem that Schaeffer describes is at the heart of what Thaddeus Williams seeks to address in his new book Confronting Injustice without Compromising the Truth.

The concept of “social justice” has been around for a long time. For example, death penalty laws date as far back as the 18th Century B.C. King Hammurabi of Babylon codified the death penalty for 25 different crimes. Likewise, many ancient tribes formed moral codes based on ideals of communal health and justice. Similarly, Western culture developed societal ethics founded on Judeo-Christian values. Both the Old and the New Testament are explicit in articulating rules and principles for spiritual and social good.

Williams is definitive about the Bible’s clarion call of social justice. “Social justice is not optional for the Christian,” he writes. “God does not suggest, He commands that we do justice.”

The problem, as Williams notes, is not that the Bible is unclear about what social justice is, but that there are many competing ideas about what social justice should look like.

“…the Bible’s call to seek justice is not a call to superficial, knee-jerk activism. We aren’t commanded to merely execute justice but to ‘truly execute justice’ (Jer. 7:5). That presupposes there are untrue ways to execute justice, ways of trying to make the world a better place that aren’t in sync with reality and end up unleashing more havoc in the universe. The God who commands us to seek justice is the same God who commands us to ‘test everything’ and ‘hold fast what is good.'” (pg. 3, italics in original)

Civil Rights leader John Perkins, writing in the book’s Forward, cautions us that in the midst of “much confusion, much anger, and much injustice… many Christian brothers and sisters are trying to fight this fight with man-made solutions [that] promise justice but deliver division and idolatry [and] become false gospels” (p. xvi). Like Schaeffer warned us, it is possible to “do the Lord’s work” — in this case fighting social justice — in unjust, worldly ways.

“We can’t separate the Bible’s commands to do justice from its commands to be discerning.”

Making this distinction is central to Williams’ thesis. He writes, “We can’t separate the Bible’s commands to do justice from its commands to be discerning.” In fact, this need for “discernment” is essential because of the increasing proliferation of social justice causes and their emphasis in culture.

Numerous fields and institutions have embraced and emphasize social justice causes. For example, many cosmetic brands are now openly engaged in activism, while children’s books like “Woke Baby” and “A is for Activism” are sold alongside Toys for Activism. There’s a Social Justice Glossary and a Social Justice Dictionary for those seeking to hone the lingo. Of course, this emphasis on activism, equity, and social causes has led to absurd over-reach and comical fails. Like the “study” which revealed that white-colored robots are evidence of racism, or the fact that a birth coach was forced to resign for saying only women can have babies. It’s also led to some notable resignations, like Peter Boghossian’s recent departure from Portland State University, claiming that the school “has transformed a bastion of free inquiry into a Social Justice factory whose only inputs were race, gender, and victimhood and whose only outputs were grievance and division.” Likewise, many institutions and organization are becoming “a Social Justice factory,” touting their own advocacies and training employees or students to embrace their approved causes.

But are all these social justice efforts aligned with a biblical worldview?

“The problem is not with the quest for social justice,” Williams says. “The problem is what happens when that quest is undertaken from a framework that is not compatible with the Bible” (p. 7). Thus, Williams proceeds to distinguish between what he calls “Social Justice A” (biblical social justice) and “Social Justice B” (unbiblical social justice). To tease out the differences between these two rivals, Williams proposes 12 questions to assist us in discerning. Those questions form each chapter. They include:

- Does our vision of social justice take seriously the godhood of God?

- Does our vision of social justice acknowledge the image of God in everyone, regardless of size, shape, sex, or status?

- Does our vision of social justice make a false god out of the self, the state, or social acceptance?

- Does our vision of social justice take any group identity more seriously than our identities “in Adam” and “in Christ”?

- Does our vision of social justice embrace divisive propaganda?

- Does our vision of social justice promote racial strife?

- Does our vision of social justice turn the “lived experience” of hurting people into more pain?

These questions get to the heart of many contemporary social justice causes, and how they differ from Scripture. For while many of these causes hew closely to biblical concerns, they often veer from equally biblical precedents.

Take for example Williams’ first question: Does our vision of social justice take seriously the godhood of God? At its heart, all injustice is a violation of the first and greatest commandment to ‘Love the lord your God with all your heart’ and to ‘love your neighbor as yourself. ‘

“Look deep enough underneath any horizontal human-against-human injustice and you will always find a vertical human-against-God injustice, a refusal to give the Creator the worship only the Creator is due. All injustice is a violation of the first commandment” (p. 18).

From a biblical perspective, all injustice is, first, evidence of our broken relationship with God. True social justice can never be achieved as long as the human heart is disconnected from God. Nevertheless, many social justice causes never take into consideration this gulf between God and Man. Until we make peace with God, there will never be peace on earth… no matter how many causes we platform.

“…the human tree is so hopelessly sick that whatever soil you plant it in, toxic fruit will form. No amount of political revolution, social engineering, or policy tweaking will stop envy, strife, deceit, and maliciousness from sprouting out of our sick hearts” (p. 17)

Not only do we need to discern the spiritual roots of injustice and its address, we must be wise in interpreting data and interrogating claims. Many calls for social justice are based on charges of injustice. But not all of those allegations are necessarily cut-and-dried, nor are their correctives. Even seemingly obvious cases of racial discrimination can be more complicated than they first appear. In his chapter “The Disparity Question,” Williams dissects some common charges of racial disparity. Like the claim that blacks being rejected for home loans at roughly twice the rate of whites is proof of institutional racism. Rather than simply concede that narrative, Williams looks deeper. Couldn’t this fact be due to stark differences in average credit scores between blacks and whites? Especially given the fact that “black-owned banks turned down black applicants… at a higher rate than did white-owned banks” (p. 82)?

Racial disparity can indeed be evidence of injustice. However, Social Justice B (unbiblical social justice) interprets ALL disparities through the lens of systemic racism. As best-selling author Ibram X. Kendi wrote in the New York Times, “racial disparities must be the result of racial discrimination… When I see racial disparities, I see racism” (p. 81). Nevertheless, Williams articulates how the real world is far more complex than this simple formula implies. For example, “twenty-two of the twenty-nine astronauts in the original Apollo space program were firstborns… Asians are underrepresented in the NBA… Women are overrepresented in health-care… Jewish people [received] ’32 percent of Nobel Prizes in medicine and 32 percent in physics’” (p. 82-83). So is racism the best explanation for these disparities? Could other, more complex social and individual dynamics be at play?

Another example Williams gives of disparate outcomes is the percentage of Asian and Jewish students at Ivy League schools. From 2007 to 2011 Asians made up 16% of the student population, while Jewish students made up 23%. However, in the U.S population, they make up only 5.6% and 1.4%, respectively. Williams says, “In other words they’re overrepresented by factors of 3 and 16. Does this prove that the Ivy League is riddled with Asian and Jewish supremacy? Of course not” (85).

In this sense, biblical justice is far more nuanced than contemporary social justice. It does not apply knee-jerk interpretations to data and implement sweeping quota applications to “correct” the perceived disparities. Biblical social justice does not punish one for hard work or intellectual development simply because they belong to a certain demographic tribe. Neither would it refuse promotion or withhold advance from a minority simply because of their skin color or ethnic background.

“The more fully committed we become to a vision of justice in which unequal outcomes are automatically assumed to be the result of injustice, the more our quest for justice will lead, indeed it must lead, to the use of power to enforce sameness. …Different outcomes are the price of freedom. The converse is also true. Tyranny is the price of equal outcomes” (86–87).

Another critical element of unbiblical social justice is its emphasis upon individual, lived human experience. Williams addresses this in his chapter entitled The Standpoint Question: Does our vision of social justice turn the quest for truth into an identity game? Here, Standpoint Theory is called into question. Standpoint Theory is an outgrowth of Critical Theory. According to Pluckrose and Lindsay, it is “the idea that one’s identity and position in society influence how one comes to knowledge” (“Cynical Theories,” p. 117 ). As such, individuals’ experience, especially as it relates to minority and identity particulars like race, economic standing, and gender, become vital. Systems of knowledge are construed that position individuals in or outside of perceived power structures. Thus, elevating “minority knowledge” (meaning ‘truth’ as experienced by a minority class) flips the status quo. As Pluckrose and Lindsay note, “knowledge is inadequate unless it includes the experiential knowledge of minority groups” (p. 196). Not only does one’s individual experience determine what is “true,” but their identity particulars make that unique truth more important to the societal whole.

Contemporary Social Justice is deeply tethered to Standpoint Theory. As Neil Shenvi notes, Standpoint Theory claims “that members of oppressed groups have special access to truth because of their ‘lived experience’ of oppression. Such insight is unavailable to members of oppressor groups, who are blinded by their privilege. Consequently, any appeals to ‘objective evidence’ or ‘reason’ made by dominant groups are actually surreptitious bids for continued institutional power.” This is why certain social justicians have made absurd claims about how things like logic and mathematics are simply racist “Western constructs.” Thus, marginalized groups like LGBTQ individuals, American blacks, Native Americans, or the handicapped are seen as having access to unique spheres of insight. As Williams puts it, “Those on the oppressed side of the equation are often granted automatic authority” (p. 156).

But is such a concept biblical? While lived experience indeed taints one’s beliefs and experiences, the Bible does not describe truth as something subjective, something that changes according to skin color or economic status. Williams anticipates such charges:

“Critics will point to my melanin, gender, sexual orientation, economic status, or faith to attack the ideas I am setting forth. There will likely be charges of fragility, blaming the victim, and protecting my privilege. …The problem is that ideas don’t have melanin, private parts, or bank accounts: people do” (PP 153-154).

Through this lens, even Jesus has been cross-examined because He was a Jewish Man. Indeed, some claim that Jesus had to unlearn His own racism and sexism! Such is the logic behind identitarianism and standpoint epistemology. It’s just one of the many reasons we must be discerning as we analyze social justice causes.

We must be cautious critiquing certain social justice claims lest we be perceived as condoning injustice. Tragically, such thinking has led many to withhold the necessary analysis.

Michael Agapito, in his review of Williams’ book at Christianity Today, offered a lukewarm recommendation. His concern was that “some will use it as an excuse to remain overtly comfortable with the status quo.” This critique has proven common among those sympathetic to social justice causes. In other words, we must be cautious critiquing certain social justice claims lest we be perceived as condoning injustice. Tragically, such thinking has led many to withhold the necessary analysis. Williams repeatedly clarified his intent was not to condone apathy. In the preface to his book, Williams writes,

“I care about God, I care about the church, I care about the gospel, and I care about true justice…. Not all, but much of what is branded ‘social justice’ these days is a threat to all four of those things I hold dear” (p. xviii).

Doing the Lord’s work the Lord’s way means being courageous enough to buck worldly trends and push back against unbiblical ideas and solutions. Indeed, history is brimming with stories of injustice procured via the stated cause of “justice.” Genocides, internment camps, lynchings, and gulags have ensued, all under the guise of securing justice. Thankfully, Williams had the courage to push back against the idol of Social Justice.

Confronting Injustice without Compromising the Truth is one of the best books I’ve read on Social Justice from a biblical viewpoint. With social justice now trending, much of it unmoored from a solid biblical worldview, I’ll be recommending Williams’ book often.