Apologist Frank Turek’s book, Stealing from God: Why Atheists Need God to Make Their Case, expounds upon the premise that atheists must borrow from theists in order to make their points. For example, in order to argue that the existence of suffering and evil proves there is no God, one must appeal to an Absolute Good. We know what is Evil because we intuitively know what is Good. But if there is an Absolute Good that transcends the material world, where did it come from? In other words, atheists must appeal to a transcendent metaphysic in order to make moral arguments against God.

A similar dynamic is at work with secular creatives. Many contemporary artists and mythmakers are atheists or agnostics. Nevertheless, they appeal to transcendent spiritual concepts or gauzy metaphysical absolutism upon which to ground their mythologies.

For example, Stanley Kubrik was described at various times as either atheist or agnostic. He is included in a list of Famous Atheists by Atheist Alliance International. However, he also described the film 2001 as providing a glimpse into his “metaphysical interests.” Said the director, “I’d be very surprised if the universe wasn’t full of an intelligence of an order that to us would seem God-like. I find it very exciting to have a semi-logical belief that there’s a great deal to the universe we don’t understand, and that there is an intelligence of an incredible magnitude outside the Earth. It’s something I’ve become more and more interested in.” Indeed, the capstone of 2001 is a mind-bending psychedelic transformation of the protag into a divine-like Star Child. Of course, the “God-like” intelligences Kubrik hypothesizes could simply be an extension of the “sufficiently advanced technology” Arthur C. Clarke postulated. In either case, in Kubrik’s squishy atheistic outlook, an “intelligence of an incredible magnitude [may exist] outside the Earth.”

James Cameron is an avowed atheist who even went so far as to call agnosticism “cowardly.” Nevertheless, Cameron’s epic 3D film Avatar creates a vast mythology all its own. The story centers around the Na’Vi, indigenous aliens who save themselves and the movie’s hero through their faith in Eywa, the “All Mother,” a pantheistic deity which is described variously as a network of energy and the sum total of every living thing. While “All Mother” “does not take sides” but only balances nature, she appears to co-opt Western morality as She sees convenient. As I wrote in Avatar’s Fickle Deity, “all the while Avatar is pushing a New Age, Neutral Deity, that Deity is busy acting very non-New Age and un-Neutral, arming her forces to the teeth. In the end, the Impartial, Impersonal Force of Cameron’s world turns partial and personal, comes to the rescue and turns, tooth and claw, on the bad guys.”

Atheist artists, though disbelieving in a spiritual dimension, often evoke the fantastical in their work, something outside of the material world.

Similar incongruities can be found in atheist creatives like Joss Whedon, Doug Adams, Neil Gaiman, Phillip Pullman, or Isaac Asimov. Atheist artists, though disbelieving in a spiritual dimension, often evoke the fantastical in their work, something outside of the material world, whether love, morals, metaphysics, non-material intelligences, or invisible terrors. Although they disavow a Creator and embrace a world without meaning, they still imbue their own creations with wonder, magic, hope, and purpose.

Film director Guillermo del Toro may be at the top of this list of artists.

An exposé in The New Yorker entitled Show the Monster, builds upon biographical tidbits from the director’s Catholic upbringing and their devastating impact, describing del Toro now as a “raging atheist.” He is listed in the IMBD database of Atheist Film Directors. At The Hollowverse, a site that aims to highlight “The religions and political views of the influentials,” de Toro is described as being “somewhere between an atheist and an agnostic…”

Despite this, del Toro’s films are packed with images of the fantastical and otherworldly — angels, demons, religious symbology, and the perennial battle of Good and Evil.

In his interview at NPR, the apparent discrepancy of “his interest, as an atheist, in spirituality” is noted. Del Toro responds:

“I have a lot of spiritual curiosity and beliefs… I believe there is a spiritual dimension, without a doubt, to both our world and our existence in it. What I don’t like is organized religion… A lot of us are born with a clear feeling of what is right and what is wrong, and ultimately are governed by that, and I think there is a spiritual dimension to this.”

So is it possible to be a true atheist and still believe that “there is a spiritual dimension” to life? Perhaps this is why some interviewers characterize del Toro as “a divided soul.”

In his feature on de Toro, Guardian writer Mark Kermode describes the director this way,

In essence, del Toro is a divided soul, a realist attuned to the strange vibrations of the supernatural, a lapsed Catholic (‘not quite the same thing as an atheist’) with an interest in sacrifice and redemption who turned down the chance to direct The Chronicles of Narnia because he ‘wasn’t interested in the lion resurrecting’.

Indeed, the influence of Catholicism upon the director, and his current aversion to “organized religion” — and apparently the Resurrection of Christ — reveals much about del Toro’s cinematic vision.

Shaped by the traditional Catholic religion in Mexico, extreme notions of sin, guilt, and penance were driven home upon the young man. The Hollywood Reporter describes one incident:

…Josefina [his grandmother] placed jagged metal bottle caps inside his shoes, “upside down, so that I would bleed to mortify the flesh to pay for purgatory,” [del Toro] remembers. “My mother discovered them and said, ‘Don’t do that again.’ But there were many bottle caps, metaphorically, that were put in there. I formed a bond with her that was full of guilt, because she explained to me things like original sin, and that was really difficult for me to understand. The notion of sin, the notion of damnation — there is a lot of pain in the Catholic religion in Mexico; there is a lot of guilt.”

But this religious influence took on even darker turns when his grandmother attempted to exorcize the boy. “She exorcised me a couple of times,” he said. “Threw holy water at me.”

Could this explain both the director’s disavowal of religion and the proliferation of religious themes in his works?

In his interview with NPR, del Toro describes his vampire trilogy, The Strain, as containing “a lot of ruminations that are almost of a spiritual nature” which occurs in “a world where you come to realize that we all are pawns of a battle between good and evil, that our actions can be measured in spiritual terms.”

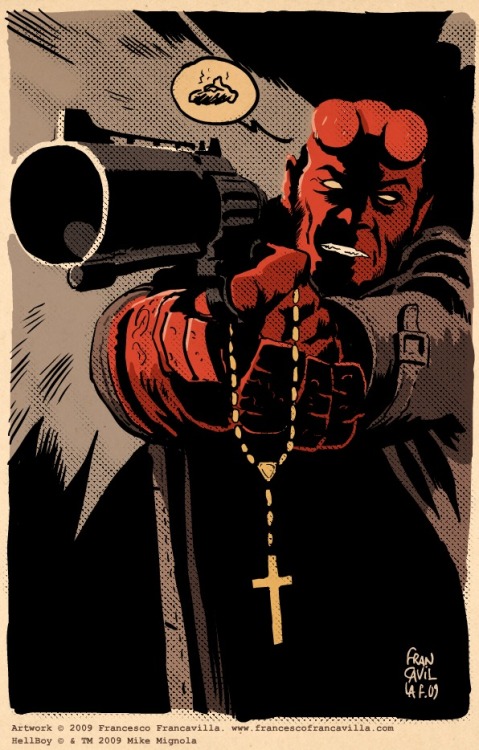

By: Francesco Francavilla

In her article, Patron Saints Of Imperfection: On Guillermo Del Toro’s Love Of Monsters, Priscilla Page expounds upon the religious themes in del Toro’s cinematic replication of Mike Mignola’s popular graphic novel.

Hellboy opens on an image of Christ on the cross at the scene of Hellboy’s birth. Hellboy carries his adoptive father Professor Broom’s rosary, and at the film’s climax, his handler Agent Myers uses the rosary to remind him who he is: even though he’s destined to usher in the apocalypse, Hellboy can resist his fate, and he chooses to do the right thing by not ending the world.

In the scene described above, Hellboy stares at the image of the cross burned into his palm and reawakens to his calling, snapping off his newly grown demon horns before saving his friends and father’s legacy.

So while del Toro is critical of organized religion and traditional theistic forms of belief, he still tells cinematic narratives that are spiritual in nature, filled with myth and magic. Which is why many see his work as compatible with a Christian worldview.

For example, actor Doug Jones, who’s played numerous characters in del Toro films (like Abe Sapien in Hellboy I and II, the Faun and the Pale Man in Pan’s Labyrinth), wrote the Forward to The Supernatural Cinema of Guillermo del Toro, a series of academic essays on the director’s work. Jones, a Christian, confesses that when asked to consider a role in Hellboy, a film about a repentant demon from hell, he initially thought he would have to decline the film because it would offend his “Christian sensibilities.” Instead, Jones discovered that the storyline contained numerous redemptive references and imagery that bolstered a biblical view of the world.

However, despite del Toro’s affinity for religious themes and belief that “we all are pawns of a battle between good and evil,” there are tremendous inconsistencies and contradictions in the director’s worldview. For instance, in his interview at Big Think entitled Guillermo del Toro’s Personal Religion, the director boiled his philosophy of life down into a rather simplistic, if not obscure, moral obligation:

“You just need to try to be a good man. To a certain degree. You know? As good a man as you can be. Whatever that measure is, be it you’re a serial killer, a war hero, or a Samaritan, whatever you are, be as good a man as you can be.”

In del Toro’s universe, being good, whether a “serial killer” or a normal guy, is the sole path to redemption, the crux of a life well-lived. Of course, such a conclusion is ultimately ambiguous. Especially as a professed atheist. What does it mean to be a “good person”? Who sets the standard of “Good”? Are the standards of Goodness different for everyone? And what does being good redeem us from, or to? In an atheistic universe, there is no heaven or hell. So whatever being good earns us, it is temporary. In the end, if the world is simply a complex bundle of material forces, being a Moral person results in nothing.

But such is the religion of postmodern man — denouncing organized religion and Moral Absolutes doesn’t just free him from fairy tales, it licenses him to remake them.

An article in SF Gate touches on this. It portrays one of del Toro’s most popular films, Pan’s Labyrinth, as a synthesis of many religious views. One religious scholar even sees the film as embodying a “broader shift in society’s attitude toward organized religion.”

The theology of “Pan’s Labyrinth” represents a much broader shift in society’s attitude toward organized religion, says Robert Johnston, author of “Reel Spirituality: Theology and Film in Dialogue,” who loved the film.

“Pan’s Labyrinth” “is representative of the turn from religion to spirituality,” says Johnston, professor of theology and culture at Fuller Theological Seminary, an evangelical Christian university in Pasadena and the largest seminary in North America. “There’s a deep and growing distrust of structures of religious systems and a turn to the construction of personal belief.

Johnston not only observes a “theology” in del Toro’s films, but he sees it as part of “a much broader shift in society’s attitude toward organized religion.” Postmodern culture has caused a shift away from collective, institutional worldviews to more individualized, “personal beliefs.” Notice: del Toro’s rejection of religion did not lead to his abandonment of theology, but his reworking of it. As Tim Keller notes in The Reason for God, “You can’t evaluate a religion except on the basis of some ethical criteria that in the end amounts to your own religious stance” (pg. 10). In this sense, del Toro did not abandon religion; he simply swapped out one for another.

Denouncing organized religion and Moral Absolutes doesn’t just free postmodern Man from fairy tales, it licenses him to remake them.

J.R.R. Tolkien famously saw the invention of Middle Earth and acts of Christian creation as “sub-creation.” He said,

“We have come from God, and inevitably the myths woven by us, though they contain error, will also reflect a splintered fragment of the true light, the eternal truth that is with God. Indeed only by myth-making, only by becoming ‘sub-creator’ and inventing stories, can Man aspire to the state of perfection that he knew before the Fall.”

Likewise, C.S. Lewis used his love for mythology to populate his own fairy tales. The Chronicles of Narnia are tethered to a biblical worldview and intended to “reflect a splintered fragment of the true light.”

For the theist, fairy tales are “sub-creations” within a larger Creation, mythologies formed to reflect “eternal truth.” Sadly, the atheist creative can make no such claims.

Which makes Guillermo del Toro a bit of an anomaly.

“When you go to a theater,” he said, “it’s like you’re going to church. You sit in a pew, and you look at an altar…”

While the director is correct about the power of film to invoke inspiration or transcendence, his lack of religious and moral certainty undermines his cinematic brilliance. For if “we all are pawns [in] a battle between good and evil,” then it behooves us to define “good and evil” beyond one’s subjective whim. Which del Toro does not. Though he believes in “a spiritual dimension,” he is hard pressed to impose any moral parameters or religious creeds upon it. But is simply being “a good man” really all there is?

In the end, the reason why Hellboy’s “redemption” was so powerful is because it invoked an “eternal truth” in a real, historically grounded Redemption. The rosary that the tortured demon carries is a reminder of Something bigger, deeper, and truer than his twisted nature. Del Toro’s fairy tales work, in part, because they borrow from the traditional morality and religion they reject.

Yes, the “church” that Guillermo del Toro preaches at is wildly entertaining. However, the postmodern fairy tales he tells only have power insofar as they appeal to the “eternal truths” of their theistic heirs.