Literary criticism tends to follow the spirit of its age. This is nowhere more evident than in the genre of horror.

More recent literary interpretations of seminal works of horror like Frankenstein, Dracula, and Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde have leaned into critical theory and postmodern deconstruction, giving way to interpretive excess and reductive textual nit-picking. Whereas Bram Stoker’s Dracula was initially read as a reaction to Victorian era mores, as culture drifted further away from those values, the “monster” took on more sympathetic, if not heroic, proportions. Similarly, stories like Frankenstein were initially viewed as cautionary tales against playing God. Yet such obvious interpretations are now far too mundane. Now critics view the tale through the lens of queer theory and transexuality, with the Monster even representing “aspects of body dysmorphia.” Likewise, Stoker’s Dracula has been charged with everything from misogyny, to racism, to homophobia, even “ecophobia” or “fear of the unknown in nature” (via “gothic ecocriticism”).

As Professor Elizabeth Miller summarized, “The text of Dracula has been subjected over the years to a painstaking search for linguistic fig-leaves as words are squeezed for every erotic potential.” A recent article at Tor magazine is a reminder of the tedious textual wringing that Stoker’s tale continues to endure.

Pastor and podcaster J.R. Forasteros’ piece entitled Fear of Desire: Dracula, Purity Culture, and the Sins of the Church is a good example of how postmodern deconstruction induces interpretive over-reach. He writes,

Monsters are omens; they warn us something isn’t right. The vampire has, for centuries, been warning us that the Church has a problem with desire. That rather than do the difficult work of discerning how we might rescue a message of liberation from the forces of oppression that pervert it, we have settled for demonizing those we’ve shoved to the margins, the easier to cast them out. In doing so, we have become the very monsters from whom we claim to offer protection.

Apparently, for Forasteros , the real “monster” of Dracula is the Christian Church. It has succumbed to “forces of oppression,” perverted its intended message, and “settled for demonizing” the marginalized. So it is no longer the spawn of hell (vampires) that we should fear, but the soldier of the cross.

More specifically, Forasteros frames “sexual desire” as a bogie created by the Church.

Vampires—as Stoker and {Anne] Rice imagine them—are monsters that arose from Christianity’s particular fascination with desire, particularly sexual desire.

The Church’s “particular fascination with [sexual] desire” has culminated in something called Purity Culture.

Apparently, it is no longer the spawn of hell (vampires) that we should fear, but the soldier of the cross.

Joe Carter describes the Purity Culture movement this way:

“Purity culture” is the term often used for the evangelical movement that attempts to promote a biblical view of purity (1 Thess. 4:3-8) by discouraging dating and promoting virginity before marriage, often through the use of tools such as purity pledges, symbols such as purity rings, and events such as purity balls.

Criticisms of Purity Culture come in two different forms. On one hand were those who claimed “it overemphasized the importance of sex, de-emphasized grace, and added unnecessary rules to male-female relationships.” On the other hand are those who “reject the biblical perspective on sexuality and frame their concerns on secularized (or in the case of some Christians, antinomian) views of sexuality.”

While Purity Culture has had plenty of critics, and in many cases deservedly so, Foresteros clearly intends to ensure it is framed in the most deliciously despicable way possible. He writes,

Purity culture is rooted in white, hetero, cis-gendered patriarchy. As such, Purity Culture defines sex, sexuality, marriage and family narrowly (ironically, not through the lens of the cultures found in the Bible but through the lens of the modern nuclear family). And thus, desire is dangerous. Desire is, we might say, monstrous.

While the problems with Purity Culture are well-chronicled, many of the claims, including Forasteros’, are inflated. As a result, nowadays Purity Culture is blamed for all manner of evil: encouraging “Rape Culture,” inciting incest, making some women fat, causing others to become afraid of men, shaming victims, and the list goes on. All the while, testimonials or teachings of Purity Culture are commonly mocked and its supporters are often caricatured as narrow-minded medieval prudes.

This may be the first time, however, that this short-lived evangelical movement has been equated with the vampire archetype.

Of course, Forasteros is correct when he writes that “Vampire stories are always about desires.” Where he errs is in framing “desire” as something monstrous to Christians. Within this interpretive framework, the vampire “embodies the Church’s fear of desire.”

…by externalizing our fear of desire into a (fictional) form we can exorcize (by way of a stake to the heart), we imagine we have defeated the monster. Just as by externalizing our fear of desire into a (female) form we can control (through purity rings, one-piece bathing suits, and calls for modesty), we imagine we have conquered desire.

Through this interpretative lens, one is able to demonize the Church but also the traditional sexual mores she espouses. Thus, the Church becomes the true monster and her “fear of desire,” a mutation.

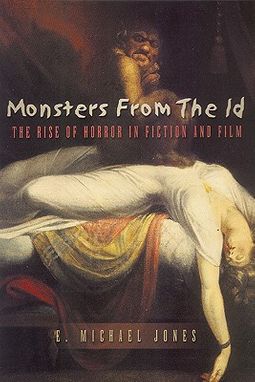

Contrast Forasteros’ approach with that of E. Michal Jones’. In Monsters from the Id, Jones posits that the origins of modern horror are as a reaction to the Enlightenment worldview. It was the Enlightenment’s subversion of religion, rejection of the supernatural, challenge of traditional morality, acclamation of man’s primary urges, and scientific pretension which created the classic monster archetypes like Frankenstein, Dracula, and Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. Horror fiction, Jones argues, was a reaction to the sexual decadence of the Enlightenment. Rather than being a critique of Victorian mores, as many commonly interpret the text, Dracula is the evil spawned by the abandonment of said mores.

In this sense, Dracula is not about “staking” sexual desire, or more specifically a “fear of desire,” as Forasteros suggests, but confronting the monster created by promiscuity and unchecked sexual passion.

As Chuck Colson summarized in his review of Jones’ works,

The avenging monster from the id, as Jones calls it, took new form during the second phase of the Enlightenment — a time when syphilis had contaminated European blood. Tragically, adulterous husbands often infected their innocent wives. DRACULA — a novel about a vampire who infects the blood of innocent girls — symbolizes this deadly plague. Dracula’s author, Bram Stoker, had syphilis himself.

Indeed, it is commonly believe that Stoker died of syphilis. According to Wikipedia, Stoker’s death certificate “named the cause of death as ‘Locomotor ataxia 6 months’, presumed to be a reference to syphilis.” Not only was syphilis the cause of widespread death in Europe at the time, its symptoms were physically monstrous, producing sores and nodes on its victims. The final degenerative stages of the disease were marked by severe mental and physical decline. Stoker likely suffered with Neurosyphilis which, among other things, made one averse to light, misshapen, and by even grow fangs. This is why some scholars see “Dracula” not as an allegory of the Church’s sexual repression, but just the opposite — the monstrous effects of promiscuity and sexual license.

Some scholars see “Dracula” not as an allegory of the Church’s sexual repression, but just the opposite — the monstrous effects of promiscuity and sexual license.

For Jones, the evils of horror are the result of suppressing morality or blatantly disavowing it. Controlling desire isn’t evil, recklessly indulging it is. The real monster, according to Jones, is the shame, guilt, and regret it breeds. The Bible teaches that Law of God is written into the heart of every human being. We know that we are sinners, our consciences condemning our own evil actions (Rom. 2:15). Jones posits that horror films are popular not because people are sinners, but because they refuse to admit it. It is a guilty conscience that punishes unrepentant sinners, especially those who’ve violated God’s sexual code. In this sense, the Monster is Remorse, which Jones defines as regret without repentance.

While Purity Culture definitely had its problems, the call to “sexual purity” is a thematic constant in Scripture. The Apostle Paul wrote, “For this is the will of God, your sanctification: that you abstain from sexual immorality; that each one of you know how to control his own body in holiness and honor” (II Thess. 4:3-5). Peter encouraged his readers “to abstain from the passions of the flesh, which wage war against your soul” (I Pet. 2:11). In fact, marriage is specifically commissioned as a remedy to “sexual immorality” in which “each man should have his own wife and each woman her own husband” (I Cor. 7:2). In spite of the fact that some describe the Church as having a “particular fascination with [sexual] desire,” it can’t be denied that, biblically speaking, sexual purity and self-control are virtues God desire we aspire to.

Not coincidentally, many who disavow Purity Culture also disavow traditional Judeo-Christian sexual ethics. I still recall debating a professing Christian women who was a vocal critic of Purity Culture. Now, she considers herself a “non-binary queer” who’s written a book on transitioning. Josh Harris, author of the popular book recommended in Purity Circles, I Kissed Dating Goodbye, famously announced that he was divorcing his wife and abandoning Christianity. Furthermore, Harris has announced himself an ally of LGBTQ+ representation. Then there’s individuals like this who announce swinging “from purity culture to hookup culture.”

Is the condemnation of Purity Culture synonymous with the rejection of the traditional Judeo-Christian sexual ethic? No. However, their intersection is ubiquitous.

Forasteros concludes that the vampire “embodies the Church’s fear of desire—desires that are unbound, that spill out of the narrow confines of the pews and want that which is forbidden.” What he fails to address, however, is the casualties of sexual license and the Bible’s clear condemnations against sexual immorality.

Truth is, “sexual desires” can indeed become monstrous. Stoker’s death from syphilis is evidence of that.

Unbridled passion is always monstrous.

As Jones put it, “horror involves both the result [of the Enlightenment’s morality] and the inability to face the moral cause.” The moral monsters we encounter are often produced by our rejection of Christian morality, and our embrace of the Enlightenment’s ethos of personal liberation, especially in sexual matters.

The vampire archetype is far from a reaction against Purity Culture and its equivalent sexual codes. Rather it is a condemnation of sexual promiscuity and the unhitching of desire from its stable. Passion is good… in the proper context. Unbridled passion is always monstrous. The “monster” of Stoker’s story is not the demonizing of desire, but the insatiable mutation of it. Dracula embodies rampant sexual desires, not the repression of them.

Which is why it is the cross and the soldiers of the cross who defeat Dracula.

Demonizing the Church is status quo for social critics. Sadly, that sentiment has seeped into literary criticism. Nevertheless, the monsters of horror, both the genre and in 21st century culture, are byproducts of our rejection of Christianity, not our embrace of it.

If you’re clever enough with words, anything can be analogous to anything you’d like. Purity Culture came preloaded as ridiculous to most non-Christians, so it makes sense that it would be the target of a trouncing.

I remember the Josh Harris thing. Don’t need God when you have $$$ and you know people will support you if you transition from Christianity.