A literal void occupies center stage in “Outer Range,” the new Amazon Western/Sci-Fi series. Sadly, a spiritual void prevents any significant metaphysical messaging from the show’s creators.

(Spoilers will follow for Season One.)

Shortly after mentioning the show on social media, and noting some of its many religious references, I was privately messaged by someone who informed me that the series executive producer and creator, Brian Watkins, used to attend youth group at their church and Bible study in college. Of course, this further piqued my interest in the show. However, Google searches regarding Watkins’ religious beliefs came up empty, leaving me to extrapolate his possible religious worldview from the show itself.

This wasn’t easy.

The series begins promising enough. Josh Brolin stars as a Wyoming rancher named Royal Abbott who discovers a mysterious void, a portal, on his vast swath of property. Strange occurrences, and tragedy, appropriately follow. The Abbott’s are drawn into the death of another rancher and its cover-up. We quickly learn that the void — an ethereal swirling hole in the earth — possesses unusual qualities. For instance, the body of the dead rancher, tossed into the void by Royal, emerges eight days later on a nearby hill. Likewise, those who enter the void experience time erratically, going forward or back without seeming reason. In Episode Two, Brolin’s character is even transported to a possible parallel universe, before returning to his present time. His discovery of the void coincides with the emergence of other geological anomalies and a series of conflicts among his family and neighboring ranchers.

In this way, the void serves as a physical and metaphorical springboard for encountering, and grappling with, the unknown.

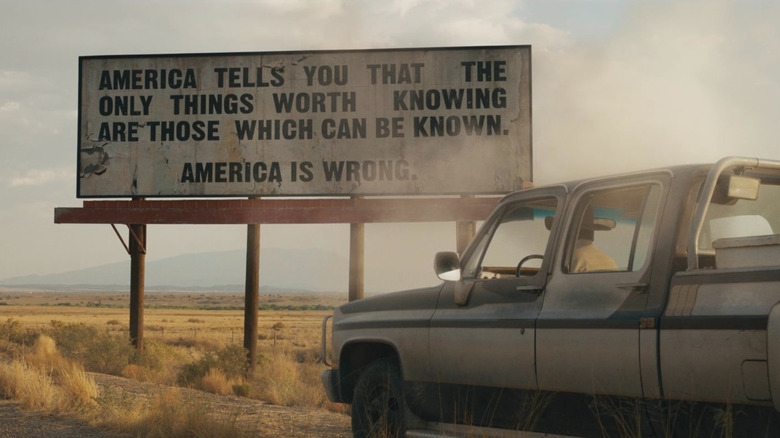

This is blatantly articulated in a strange billboard which shows up in later episodes. The billboard reads, “America tells you that the only things worth knowing are those that can’t be known. America is wrong.” That theme of encountering “what can’t be known” appears central to Season One of Outer Range.

In his interview with The Wrap, Watkins explains that the crux of the question the show is posing is “What do you do when something is unknown or unknowable or inexplicable?” He says,

I think the last few years have completely upended our notions of ourselves, of our world. I think it really is a story that is tapping into the root of those angsty feelings about the unknown. How do we deal with this? What do you do when something is unknown or unknowable or inexplicable? I think it comes back to that question of what would happen if the disenchanted world stumbled upon enchantment. I really think that’s the crux of the question that we’re trying to ask. And so I hope that’s the question that audiences ask as they watch it.

This confrontation with enchantment, with the unknown, is the thread that binds Outer Range’s main players. Throughout the series many of its characters are confronted with metaphysical conundrums and oddities.

This writer at Paste describes the void’s influence on others thus:

It’s the ultimate blank space against which any broken person can project their deepest fears; the ultimate well into which they can cast their most shameful secrets. It is both a precursor to and object of a kind of frontier-born religious ecstasy, a divine madness, a theia mania that overtakes every major player by season’s end.

Contemplating mystery and the unknowable is the wheelhouse of Scripture. God is described as the greatest of mysteries, but reveals Himself, His plans and promises, to those who love Him. Man is never promised to know everything, but to find peace in knowing the One who does. So one would think, with some apparent biblical influence in Watkins’ background, the spiritual and natural mysteries faced by his characters might point to a divine interpretation. However, the one overtly religious character in Outer Range is woefully incapable of providing hope for her splintering family.

Cecilia, Royal’s wife, is played by Lili Taylor. She is introduced as the religious matriarch. In the very first episode, we see Cecilia leading her family to church. She is seen singing “How Firm a Foundation” while her husband sits at the back of the church reading the paper. Cecilia later prays with her granddaughter, whose mother had mysteriously disappeared. An embroidered plaque in Cecilia’s office is an unambiguous reminder of her faith. It reads, “Oh Lord Reveal Yourself to Us.”

Watkins, in his aforementioned interview with The Wrap, expands upon the messaging behind the plaque.

I actually have here a crocheted hoop with a similar saying that I bought for fifty cents at a thrift store in Dubois, Wyoming, just before we were writing the show. This is my writing spot and it sat like right there for so long, but the saying of, “Oh, Lord, reveal yourself to us,” is actually something that I saw at a church in Washington State. It was a silhouette of a cowboy next to this saying, “Oh Lord, reveal yourself to us.” It was a saying that exemplifies the grand yearning of spiritual people, of people of faith that I think we don’t tap enough into, narratively speaking in our TV shows and films and stuff…

…similar to [Terrence Mallick’s] film, there’s a sincere yearning to have a revelation of what is holy and sacred. “Tree of Life,” it’s the mix between nature and grace that’s set out at the beginning of that film and it’s expressed with such… I mean, it’s so beautiful. Malick does it better than anyone else, but I think having this daily reminder in one’s workplace, in one’s office that Cecilia has, it’s just an expression of the everyday yearning that’s within her. And I think at the end of the day, this show is really about these people with deep, deep longings for something higher.

While it’s encouraging to see a contemporary filmmaker seeking to express “the grand yearning of spiritual people” and our “deep, deep longings for something higher,” by mid-season, Cecelia’s faith is shipwrecked.

For example, in Episode 5, after struggling with Royal’s growing emotional closure and the unraveling cover-up of the dead rancher, Cecilia confesses her need for prayer, saying “I just feel a little lost.” The group leader prays, “Heavenly Father… look down on our sister Cecilia here. She is lost, dear Father. Show her the way…” The scene is sandwiched with Ella Fitzgerald singing, “Get Thee Behind Me Satan.” Yet Cecilia grows increasingly Lost,” even abstaining from communion at church.

But while Cecilia is losing her faith, Royal is experiencing his own spiritual awakening. In Episode 2, after a bizarre incident in the void, he announces that he wants to say grace before supper. This startles the family. Royal prays,

Dear God… we pray for… Trevor (the dead rancher). Mm-hmm. For his family. And for our boys. Our family. We ask… that You forgive us. I guess. We ask that You show us the way here, ’cause we’re in trouble. We are desperate. Hmm. You made this crazy world. So maybe You can give us some sort of hint as to what You’re up to, ’cause I don’t have the first f***ing clue. And maybe it’s that You have nothing to do with this, or maybe You’re not even there, who knows. There is a big distance between You and us… a gap, a void… there is a great void, and I’m asking You to fill that void. I’m asking You to fill that void. I’m asking You to come down here and explain Yourself, because this world of Yours isn’t quite adding up, and I hate You for it, I really do. And I don’t even think I f***ing believe in You, but I really hate You. Hmm. Amen.

While obviously unorthodox, Royal’s prayer is the beginning of a continued trajectory into his metaphysical meandering. By Episode 8, the final episode of Season One, we hear this voiceover from Royal:

People have told me that grace is a given thing. That if you seek it, you’ll find it. When I was a kid, I’d go to church, and hear the pastor preach the word. And he’d make me feel everything in my heart. And everything in the world around me would have a little more meaning. The world was a bright place.

It worked on me. God was everything good. Then, when I was eight years old, I shot my father. When I watched that stray buckshot go into his chest and blow all his insides out his back, the world went black. Like it had ended altogether. It hit me that God is everything. Everything good… and everything bad.

This juxtaposition of Royal and Cecilia, the odd reversal of their faiths, is the dramatic cliff where Season One ends. Sadly, it also ends with very few answers.

Outer Range has a lot going for it. The acting is well done and expansive shots of green pastures stretching across Big Sky country are quite gorgeous. However, the metaphysical questions posed by Watkins and crew remain murky, at best.

Perhaps it is this promise of “answers” that made me disappointed with the show’s climax. Or knowing that a Christian was possibly manning the helm. Sure, phenomenon like the void or associated time travel are meant to remain fictionally enigmatic. Life itself is not neatly explained. However, when one sincerely prays, “Oh Lord, reveal yourself to us,” statements like “God is everything. Everything good… and everything bad” require serious fact-checking. While it is encouraging knowing the “show is really about these people with deep, deep longings for something higher,” it is equally disappointing seeing that question answered with postmodern sophistry.

Maybe Season Two will bring more clarity to the metaphysical questions posed in Outer Range. However, the answers revealed in Season One are little more than a spiritual void.