My previous post No Zombies Allowed (in Christian Fiction) prompted some interesting pushback. Becky Miller’s Reading, Truth, and the Bible over at Speculative Faith took on what she considered two faulty conclusions I make regarding speculative Christian fiction and theology. She summarizes:

…spurred by Mike’s thinking, I have long argued against both of his conclusions… 1) that a Biblical framework must by definition limit our imagination…, and 2) that Christians ought not “impose overtly strict theological expectations on our fiction.”

Commenter H.G. Ferguson applauded Becky’s critique in no uncertain terms:

Bravo, bravo, bravo!!! Thank you for such a heartfelt, intelligent and eloquent discussion. Thank you also for speaking up against the “anything goes” mentality. If “anything goes” and “it cannot be speculative enough” becomes the environment of what we write, we are lost. Because we are commanded — commanded, mind you — by God Himself to take every thought captive to the obedience of Christ. ”It cannot be speculative enough” and “no theology in our stories, please” amputates that command. What we write must flow OUT OF the scriptures, not some notion of a “theology imposed” from the top down. That’s our standard — Jesus Christ should rule what we write, as He must rule our hearts and minds — not speculations that wrest the scriptures to our own destruction and make a shipwreck of the faith once for all delivered to the saints. Thank you, thank you, thank you — and, one last time — bravo, bravo, bravo!!!

I find Ferguson’s response interesting on a couple fronts. First, his (?) suggestion that I am advocating an “‘anything goes’ mentality” in our fiction. Second, that without biblical parameters to our fiction, we potentially “wrest the scriptures to our own destruction and make a shipwreck of the faith once for all delivered to the saints.” The inference being that what Mike Duran is advocating is potentially heretical and damnable.

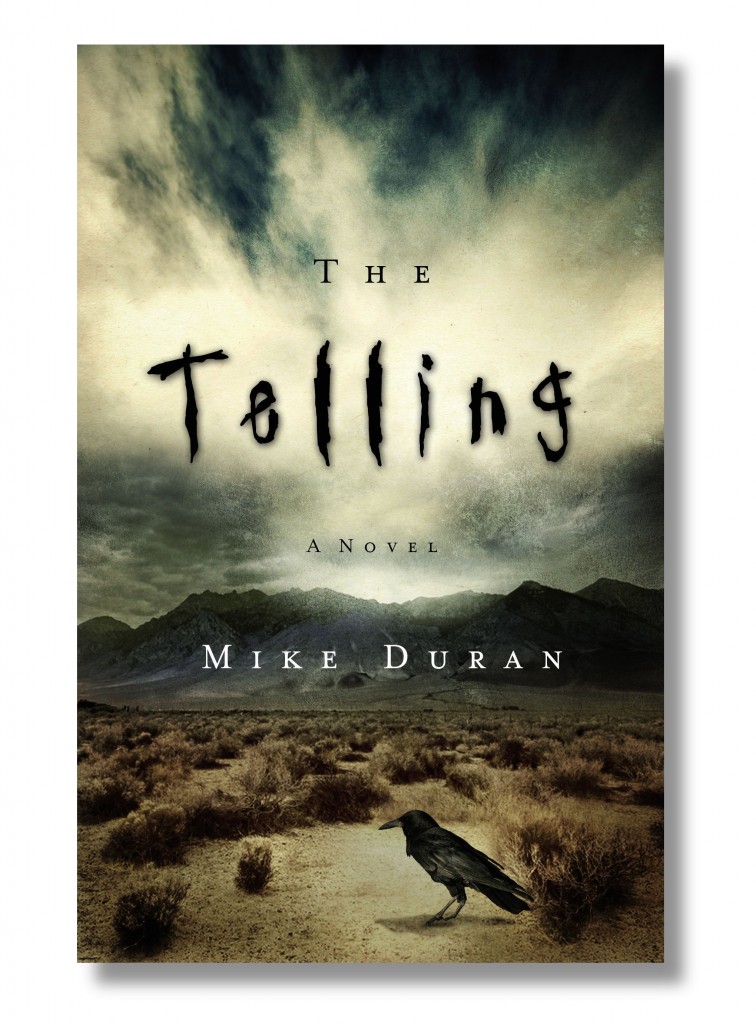

This is not the first time I’ve been accused of such. For example, in THIS REVIEW of my last novel The Telling, the author gave it three-stars, called it “eerily good,” and said some very nice things about the story. Nevertheless, they had some issues. At the top of the list:

The theology. It was definitely wacko, so unless this book is entitled STRICTLY Science Fiction, then some people could possibly be deceived into thinking this was reality… Use caution when reading this book

I’ve always thought that would make a good blurb: “Use caution when reading this book!” But what it suggests is, I think, equally troubling:

Are Christians advocating for fiction that requires NO discernment and books that can be read WITHOUT caution?

If so, I think that’s a problem. Especially when it comes to art.

Anyway, I wanted to take some time to clear up any confusion about what I am and am not suggesting. For starters, I believe Becky inaccurately frames my points. In her article, she writes:

“The error, I maintain, is Mike Duran’s position that theology ought not be ‘imposed’ on fiction.”

And secondly, she summarizes my conclusion as

“a Biblical framework must by definition limit our imagination.”

As I said in my brief comments on that post, neither of these conclusions reflect what I believe. I will address the first here and, later this week, the second.

I.) I DO NOT believe theology should NOT be imposed on fiction.

As Christians, theology should be a lens we view everything through, especially art. The apostle Paul states a good general principle that can be broadly applied to just about anything:

“Test all things; hold fast to what is good.” — I Thess. 5:21

Christians should have highly trained BS meters, constantly testing and discerning what we read, watch, and create. The question is not IF theology should be imposed on our fiction, but HOW MUCH theology should we impose upon our fiction. Or as I put it in my original article, “We impose overly strict theological expectations on our fiction.”

This is an important distinction. I am NOT advocating that Christian readers become undiscerning and uncritical of the stories we imbibe. I am not advocating an “‘anything goes’ mentality” in our fiction. I am simply asking, How much theology can we reasonably impose upon our art and fiction? Must Christians, for instance, not include zombies in their fiction unless they provide a “biblical” explanation (as in, they’re not really dead)? To me, this smacks of overkill (pun intended). Nevertheless, such is the mindset our industry has produced.

I have entertained writing a fictional story about a backwoods preacher who can turn sticks into serpents. It’s quite an unusual talent. Perhaps he does it as a means of supporting his family. Maybe he donates the critters for venom research or makes jerky out of them. Whatever. The important point here is that turning sticks to snakes has a biblical basis (Ex. 7:10-13). So does this mean I can safely write such a tale and not be cited by the theology police? It depends. Even though the miracle has a Scriptural basis, many Christians would still debate the theology of such a story. Is the preacher’s power from God? If it is, is he using that power for the right reason? Some would ask if God really performs those types of miracles anymore. Others would say that, if the snake handler is not a Christian, it must be explained that his power is of the devil. Any ambiguity about the source of the magician’s power would be theologically unacceptable. Either way, theology would become a test of the story’s Christian compatibility.

Such is the minutiae Christians endure when theology becomes the template for their fiction. Straining at gnats (or zombies), becomes par for the course.

Notice: I am NOT advocating that we forgo theological scrutiny. I’m simply suggesting that, when it comes to fiction, theme trumps theology. The fact that the conceptual springboard for The Great Divorce has no biblical foundation does not stop me from enjoying the tale in the least. Why? Because it’s fiction, for one. Secondly, the truths it elucidates are entirely biblical. Yes, the Bible says there is an impassable barrier between Heaven and Hell. But does that mean one can never ponder — in a fictional tale or elsewhere — what the citizens of Hell would do were they to encounter citizens of Heaven? Especially if that fictional encounter further illumined some biblical truths. Regardless, there are those who would begrudge such a story on the grounds that it is does not jive with sound doctrine – souls simply cannot cross from Hell to Heaven.

Sad.

Another important distinction we need make is that good theology doesn’t always extrapolate neatly into real life.

No work of fiction can perfectly encompass and/or articulate any one theological article. In whole or in part. Furthermore, can any one person or a series of events — especially fictional ones — ever live up to theological scrutiny? How about these real, biblical characters?

- Did King Solomon’s life fully reflect sound theology?

- Did Jonah’s life fully reflect sound theology?

- Did Rahab’s life fully reflect sound theology?

- Did Judas’s life fully reflect sound theology?

- Did Samson’s life fully reflect sound theology?

- Did Adam’s life fully reflect sound theology?

If we base our image of God or biblical truth on any one Bible character or story, we could find ourselves off in the theological weeds. So why should we expect any single story, much less a single story about a slice of life of any particular character, to be a model of sound theology? Just look at these fictional characters:

- Is Gandalfs’ character fully in line with sound theology?

- Is Atticus Finch’s character fully in line with sound theology?

- Is Hazel Motes’ character fully in line with sound theology?

- Is Shepherd Book’s character fully in line with sound theology?

- Is Michael Hosea’s character fully in line with sound theology?

- Is Harry Potter’s character fully in line with sound theology?

We do an injustice, I think, when we put fictional characters under strict theological scrutiny. If we’re writing a doctrinal thesis then, yes, watching your i’s and t’s is critical. But if we’re creating a fictional world, must the same rules apply? Are zombies verboten because, well, there’s no such thing?

In Christianity Today’s Odd Straight-Jacket for Christian Art Shallenberger writes this in his review of the Blue Like Jazz film:

The purpose of art, and even religious art, isn’t to proselytize, or to affirm a body of doctrine. Art exists to reveal beauty and truth. No story, sculpture, bears the whole weight of that task…

As long as we expect the arc of every faith-based story to touch a set of arbitrarily determined bases, Christian art will continue to earn the stereotype of being sentimental, emotionally dishonest, and stilted.

It’s time to take the straight jacket off our artists and let let them tell all kinds of stories. Only then will our stories of God escape the Evangelical ghetto.

No “story [or] sculpture” should “bear the whole weight” of “affirm[ing] a body of doctrine.” Much less one person! Does your life always reflect good theology? All the time? Could I determine what God is like, what the Gospel means, the nature of God’s relationship with Man, grace, evangelism, eschatology, prayer, atonement, etc., by simply observing you? (Much less doing so over a short period of time, which most stories encapsulate.)

I suppose it all comes back to what we conceive as the purpose of art. As Shallenberger writes, “The purpose of art, and even religious art, isn’t to proselytize, or to affirm a body of doctrine.” This, of course, isn’t a disavowal of theology or a dismissal of evil and immorality; it’s an admission of the nature of art and storytelling, and their limitations.

Fiction and theology are two different things.

All that to say, I DO NOT believe theology should NOT be imposed on fiction. Theology should be the lens we judge all truth claims, all art, all entertainment through. The difference between me and my detractors on this is not whether theology should be imposed upon fiction, but how strict that imposition should be.

In Part Two, I’ll discuss the second objection, that “a Biblical framework must by definition limit our imagination.”

I always thought that the value in Sci-fi was to take an aspect of culture and reflect the strength or weakness of it in the story. It can make for an uncomfortable introspection when seen through the eyes of an alien or reflected through the light of relitivistic time travel. I suppose it is one place to count the number of angels who can fit on the head of a pin.

Loved your example of the Great Divorce Mike. That nailed your point for me!

Here’s an easy solution: Christians shouldn’t write spec fic at all.

http://netraptor.org/blog/2014/02/why-christians-shouldnt-write-speculative-fiction/

You are making points I’ve made before, so would be hard to disagree with you. 🙂

I’ve complained before about people expecting a full systematic theology of the Gospel be presented in each and every book you write. Fiction simply isn’t designed to do that. I reflects the experience of Truth, not the fullness of Truth.

I’ve noticed a distinction between people who think in allegories and people who think in analogies. Allegorical people insist everything needs to line up; in an argument, if you posit an example that is untrue, they’ll declare it invalid and heretical, even when your argument isn’t supposed to be true. The people who think more in terms of analogies are more appreciative of science fiction and fantasy, because we see a valid-but-untrue argument and see, “Oh! It’s supposed to fail there!” and appreciate it for what it is, rather than what it is not.

In that sense, it could also be a distinction between people who are pessimistic vs. optimistic.

I do believe that individual people need to avoid the analogies for their own safety, because they miss the bigger meaning and get trapped on the wrong details, but that’s an individual determination. My mother’s convinced romance novels are porn for women, and I know others who insist that anybody who reads them is necessarily self-inserting. They insist that anyone who claims otherwise is lying.

When I was a biology major, my roommate was studying to be a midwife’s apprentice. I’ve discovered the hard way that some things I see as frank fact, some others find erotic. While I don’t want to cause others to stumble, I get fed up with people assuming that everyone else is triggered by the same things they are. People are different.

Even Biblical writers referred to extra-biblical sources, at times, and if strong language and references to sex are to be off-limits for the Christian, why does it appear in the Bible?

I realize I’m kinda ranting at the choir, here, but perhaps some of my thoughts will help you in framing/phrasing your thoughts. 🙂

No real comment except to say that you communicate beautifully, skillfully, clearly, and if someone chooses to misunderstand, they would have to work hard at it to do so.

“Christians should have highly trained BS meters”

Yes. I’m wondering if the dominant views on theology and Christian fiction are related to the dominant views on the weaker brother? (Which is one of your best blog posts, IMO). Meaning, the weaker brother doesn’t have a good BS meter, so we (the rest of Christendom) have a responsibility to make sure he never gets exposed to anything which might cause him to stumble … like fiction which raises questions. Any questions.

(Male pronoun used simply because of the weaker brother analogy. Women are equally likely to be the culprits here.)

I don’t know if this is at all relevant to the discussion, but I’ve found that Christian authors seem to mistake their God-given talent for writing with true inspiration from God. As far as I know, none of us is contributing to the canon. Yes, we should take care with what we write, just as we should hold to a system of integrity in any career that we have, and regarding any product that we manufacture. We should always check our motivations. But our works of fiction ARE NOT the Ten Commandments, and it is frankly arrogant of us to presume that God views them at that level.

Mike, thanks for your post. It has helped me to clarify my own thoughts on the issue. The links to other posting were also helpful.

I also agree. We are writing fiction, not biographies. One of the powers of speculative fiction is to view truth in a different way so that the truth is easier to see.

Since people like to throw bible verses at these types of discussions, here’s one to think about. (Modified for effect) (with my appologr to Paul.)

“The one who writes about undead zombies is not to regard with contempt the one who does not, and the one who does not write about undead zombies is not to judge the one who does, for God has accepted him. Who are you to judge the servant of another? To his own master he stands or falls; and he will stand, for the Lord is able to make him stand.” A modified version of Romans 14:3-4