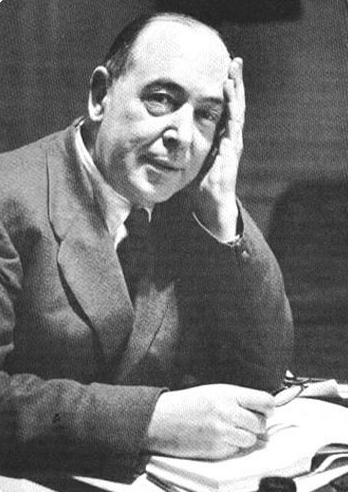

In his essay on literary criticism entitled On Criticism, in the Of Other Worlds collection, C.S. Lewis makes a distinction between intent and meaning. “It is the author who intends,” Lewis writes. “The book means.” As such, the author — not the reader or critic — is best at understanding his intent in a piece. That’s pretty obvious.

a distinction between intent and meaning. “It is the author who intends,” Lewis writes. “The book means.” As such, the author — not the reader or critic — is best at understanding his intent in a piece. That’s pretty obvious.

The author’s intention is that which, if it is realized, will in his eyes constitute success.

In other words, if the readers laugh and cry when the author hopes, he is successful. If, however, they are laughing when the author wants them to be crying, or vice versa, he has not achieved his intention.

But according to Lewis, “Meaning is a much more difficult term” to define.

The nearest I have yet got to a definition is something like this: the meaning of a book is the series or system of emotions, reflections, and attitudes produced by reading it. But of course this product differs with different readers. The ideally false or wrong ‘meaning’ would be the product in the mind of the stupidest and least sensitive and most prejudiced reader after a single careless reading. The ideally true or right ‘meaning’ would be that shared (in some measure) by the largest number of the best readers after repeated and careful readings over several generations, different periods, nationalities, moods, degrees of alertness, private pre-occupations, states of health, spirits, and the like canceling one another out when (this is an important reservation) they cannot be fused so as to enrich one another.

Notice that while intent resides in the author, meaning emerges in the readers at large. Because of this, the author is not always the best judge of his own book’s meaning.

It’s a fascinating idea that once the writer submits his piece to readers, something completely outside of his control happens: the book’s meaning emerges. Nevertheless, the “right meaning” cannot be extracted by the wrong reader, i.e., a bad one. It is only “the best readers,” the careful, diligent, unprejudiced, impartial, who can see the work for what it really is. And even then, their opinions are “fused” with other opinions, over time, until the “truth” about the piece eventually shakes out.

This is not only the idea behind criticism, but the reason we need good critics. Sure, that seems like an oxymoron — especially to a writer. Let’s face it, writers (as do artists and actors) want critics that praise them. But criticism, as an ideal, maintains a literary culture and contributes to its integrity. As Lewis puts it, the public is “entitled, at the very least, to honest, that is, to impartial, unbiased criticism. . .” In other words, writers need “good readers,” not “the stupidest and least sensitive and most prejudiced” ones.

I wonder that this — the presence of “good readers” — is one of the primary determinants to the state of contemporary literature. What with The DaVinci Code and The Left Behind series reaching mega-bestseller status, could it be there’s none left?

Don’t you think the “right reader” can extract meaning without necessarily praising or criticizing the writing itself? A story may be poorly written and yet contain ideas so profound it evokes consistent emotions, reflections and attitudes with “the largest number of the ‘best readers.'”

Just a thought.

As for different readers taking away different meanings, I love this aspect of story! We all bring experience, education, culture, bias, etc. to the page. I’m thrilled when a thoughtful reader finds meaning I didn’t intend but can clearly see once I consider his perspective. For me, that’s one of writing’s biggest rewards.

I agree with you on both points, Jeanne. George MacDonald comes to mind as one whose message transcended his mechanics. In the preface to MacDonald’s Lilith and Phantastes, C.S. Lewis commented that “Few of his novels are good and none is very good”, but that the profundity and innocence of the tales outshone the literary crudity. In fact, I think this is exactly what Lewis was getting at in this essay: that the “good reader” or critic is able to mine out those distinctions without pooh-poohing the entire piece.

And like you, one of my joys of writing is the dynamic of multiple perspectives. It makes sense that anything good or worthwhile has depth. That people extract different things out of our work should encourage us. The last thing we should want is marionette-like mastery over a readership of puppets.

Thanks for your comments, Jeanne!

Great post, Mike, and great comments, Jeanne. I love these ideas.

It also makes me think of the Bible, not that the masses determine the meaning of it (although, as we all bring our perspectives and experiences to it, listening to others with a different set better opens up the meaning), but that the human author intended something and the meaning transcended that.

I think folks like CS Lewis were fortunate in that they at least knew that “the best readers” were out there to actually read their creations. These days I think writers are simply settling for “just readers”… or maybe not even readers, but customers (ie, Left Behind, Chicken Soup for the…, ‘blank’ for Dummies, or even the Cool-slang-Jesus-is-a-Nice-Dude Bibles).

Anyway, my point is, as Tupac would say, “Everybody raps. We rap to make money. We do business.”

I could be way off on this, Mike, but I think most readers, even those who prefer fiction, are, above all, curious.

The commercial success of Left Behind and DaVinci Code have less to do with craft—good or bad—and more to do with content. In the first case, curiosity about what will be, and in the latter, curiosity about what was (or was covered up).

This may seem odd since these books are fiction, after all. I think readers understand that, but the story expands the borders of thought, allows them to consider things they hadn’t before.

I have no doubt that, had another novel with superior craft about the end times been available, it would have outsold Left Behind. Perhaps neither would have been a blockbuster had there been two. Of course none can be written now for some time because it will be viewed as derivative–EVEN IF THE PUBLIC WANTS MORE, WRITTEN BETTER.

There’s the prejudice that I think exists, and it does lie with the critics. Maybe with editors, too.

Becky

Great comments, everyone! Matty, that’s the first time anyone’s ever quoted Tupac on Decompose. And Becky, I think you’re right, to a degree, about the “curiosity” factor, primarily in the case of DaVinci and Left Behind. Nevertheless, I think indiscriminate readers probably contribute more (at least, as much) to the proliferation of such sub-standard literature than the makers. It’s hard to say whether a more discerning readership would have tolerated the books, despite the curiosity. But for this discerning reader, I was neither curious nor tolerant.

Everyone I know who read the left behind books or the code were not avid readers. Left behind flourished for a reason. Prophecy experts (term used loosely ) are so vague as to how they come to their conclusions that the general christian public were hungry for a simpler explanation.

That is the power of fiction. To break down the complex to its elemental level – a story involving people.

The reverse happened with D-code, the skeptical on the fence general public yearned for something to back up their spineless stance. Holy Blood, Holy Grail didn’t explode because it wasn’t a novel. Thus – the power of fiction shines again.

In both cases, the readers had nothing to compare these works to, so no judgement was made as to their quality as compared to contemporary works.

The first part of this post was very interesting. Made me think of high school and how I annoyed with teachers– I just wanted to read and enjoy Lord of the Flies, The Outsiders, Of Mice and Men, etc. THEY wanted to dissect and make me discern the “meaning.” I always thought, how can YOU know what the author meant? I’d get skeptical about all the themes and messages the teacher said the author intended. Now I’m starting to realize that there is a difference between intent and meaning. Even in my own writing and the feedback/crits I get, I find that other people can see things I didn’t know were there. Perhaps they are things I subconsiously put in, nevertheless they weren’t things I intended.

The end of your post annoyed me. I always bristle when you start picking on the populace for what they watch on TV or choose to read or when you suggest that so many are idiots! I bet there are lots of brilliant people whose lives are full of serious challenges, and they just like some light entertainment. How about a brain surgeon who is under serious stress all day? He’s brilliant, but when he gets home, he wants to unwind with DaVinci. Or the mom of 3 who cares for her husband, kids and home plus heads up a ministry at church. She is organized, creative, and shrewd. Makes meals thay keep her family raving, settles sibling rivaly incidents with wisdom, gets the best deals… And then she collapses with some Christian chic lit. Okay, I’m rambling. I’m just saying people have a right to read what they want to read and if their choices aren’t as literary as yours or mine, it doesn’t mean they are stupid. I think a lot of people loved Left Behind because it helped them get a picture of what LaHaye’s views of endtimes might look like. I didn’t read them all, but I read the first couple about 10 years ago. I still remember the beginning where the Christians dissapearred- cars crashing, etc. I’m absolutely no good at debating, but there’s my honest opinion. God bless!

As long as we agree that there is, what you call, “light entertainment,” then we’re on the same page, Janet. Where we probably differ is in (1) What constitutes “light entertainment,” (2) How much of it is good for a person, and (3) Why we gravitate so naturally to it.

I’d also add that, if there’s “light entertainment,” there’s other grades of entertainment, from the “heavy” to the “airy,” from the “substantial” to the “substance-less,” from pure diversion to exploitation to the obscene. So it’s a matter of drawing lines and, you’re right, people are free to draw them where they want.

While art appreciation is a subjective exercise, most people would agree that the Beatles were better than my high school garage band and that Ulysses is superior to Mike’s First Story. Maybe The DaVinci Code and Left Behind fall somewhere in between. All I’m suggesting (albeit in my snide manner) is that it’s far better to listen to the Beatles than my high school garage band, and read Joyce than Dan Brown. Watching American Idol might not make one stupid, but striving for better, deeper fare definitely wouldn’t hurt.