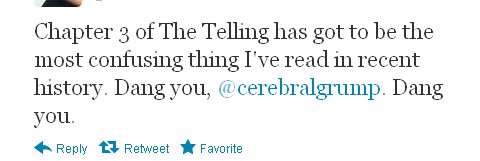

I’ve had more than one reader express confusion about Chapter Three of The Telling. Like this Tweep:

I’ve had at least half-a-dozen readers say something similar. I kind of expected it. In a way, I intended it. You see, Chapter Three introduces the reader to Fergus Coyne, my antagonist. Fergus is a very troubled man, involved in some very dark stuff. I decided to introduce him to the reader during one of his trance episodes. The chapter is really short, not quite two pages. But it’s also a rambling, seemingly disconnected hodge-podge of sensations and memories. And crucial bits of plot. Then Chapter Four returns to normal.

But honestly, I’m not sure what to make of some readers’ struggle with the chapter. If you read often, and broadly, you’ll ineviatbly come across these sorts of “difficult chapters.” You know, chapters that plop you down right in the middle of something bizarre or tense or hectic without bothering to explain. I intended Chapter Three to do something similar. Which leaves me wondering at why the chapter has been such a hiccup for some readers.

My daughter Alayna, who admirably took on the Harry Potter series and conquered it, once asked me about difficult chapters. You know, those chapters where things are going along just fine and, out of the blue, a scene or character arrives that disrupts your footing and leaves you asking questions. I told her the same thing I told the writer of the above Tweet:

Just keep reading. It will all make sense in the end.

Out of context, any chapter can seem confusing. But context only comes with a fuller understanding of the whole story. Which is why the best response, by a reader, to a confusing chapter is to simply keep reading. If it doesn’t make sense at the end, then you’ve probably got a legitimate gripe. But please don’t base your assessment of the whole book on a couple of tough chapters.

Anyway, it’s made me think about those “difficult chapters.” First, as a writer. Should writers avoid “difficult chapters” like my Chapter Three because they might confuse readers? Then again, perhaps it was my writing that confused them. If that’s the case, I need to take note. And then there’s readers. As a reader, how do you recommend approaching those “difficult chapters”?

(BTW: You can read that entire third chapter of The Telling on Google Docs HERE. But remember — this is just one chapter out of 50-plus.)

Hey, one of my favorite books is the winner of the first Hugo award, The Demolished Man, by Alfred Bester. It experimented wildly with the storytelling mechanism. I plow through occasional difficult chapters in hopes that all will be explained. (However, if the entire work is too dense to pierce, I drop it and move on to something I like better.)

Btw, to get a feel for just how experimental Bester was, check this clip out:

http://www.arthursbookshelf.com/sci-fi/bester/demolish.htm

This is why I’m not attuned to chapters, generally. I just read. To my mind the book is the book; it all fits as a unit. I’ve never been one to start and stop on chapter breaks or, really, to pay much attention to them at all. And I’ve read enough serial killer books and James Joyce to be inured to the seeming-mumbo-jumbo of “crazy fellow headspace” passages.

Mike, I read chapter 3 out of context (except for this blog), and didn’t have a problem with it. Maybe I bring TOO much to the text, but between the veil (a caul?) reference and the bone chimes, the territory was immediately familiar. The racing dark of the eclipse looks (for now) like an interesting aside but apt description of the terror of a non-lucid dream or trance, and when I hit “Gimel. Nun.” my mind flew to Psalm 119, so the language references began to fall into place. I love the image of the “unhewed word.” I’m probably making too many assumptions about the story at this point, but I’m intrigued to read the rest. I do have the book at home – found it at a Lifeway store.

As to the problem with difficult chapters, I think including them would depend on the genre, and should be a decision between the author and the editor of a house. Some reader demographics aren’t tolerant; some are, and the editor should know what works and what doesn’t. The author, however, should write what he feels the story demands.

I agree that the author should write what is necessary for the story to be told. Not trying to be harsh, but the “intolerant readers” can go back to whatever socio-religious substrata they crawled out of. And I say that in love for them. If they’re happier there, then stay there and stop bothering the rest of us who are also working out our own salvation with fear and trembling.

This didn’t seem too confusing to me. Well, I guess I should say, the confusion seems purposeful so as a reader, I’d be willing to trust that it will eventually make sense. If your first two chapters are short, I could see some readers perhaps not being ready for a POV shift yet. However, I’ve read much more confusing literature than this. Beowulf, for example.

Being the ungenerous person I am today, I think this goes back to the same problem you discussed in your article last Friday at Rachelle Gardner’s blog. The cult of stupid is alive and well. Some people don’t want to think too deeply or or add to their vocabulary or trust an author. Even if they don’t know all the answers upfront, they want the writing itself to be clear and obvious.

Oh, and I would add that if your chapter 3 is the most confusing passage somebody has read recently, that person doesn’t read a wide variety of literature. It does, however, sound as if the person might have been intrigued by it–why else would she/he tweet it? So while I stand by what I stated in my 1st paragraph, I’m not sure it applies to this person. The tweet might have been a veiled compliment.

I immediately understood the original tweet as a veiled compliment.

Your advice, just keep reading, seems so obvious. I’ve had a couple of readers who want to know everything about a character or situation the first time it’s introduced, when to elaborate would bog the entire work down. Some of those elusive details are part of the eventual resolution of a story.

I have “The Telling” on order and look forward to jumping into it. You keep writing – we’ll keep reading.

Hang in there, Mike.

Dang you, Mike, I didn’t get the memo that it was supposed to be a difficult chapter. I mean, it was not easy, but being that early in the book I knew it was setting the stage for that character, so I read it and moved on. That was near the point I wondered how many characters we’d be introduced to before the plot started joining them together.

Of course, I have been known to read over a hundred pages of a book thinking it was the worst ever before the plot started to click, so 2 pages of strange didn’t phase me a bit. I was finished with Chapter 3 long before I learned I had won a signed copy of The Telling, so that had nothing to do with it.

I don’t remember finding chapter 3 to be difficult at all. I tend to trust the author, though, to make things clear in time. The Telling was unfolding all along, as you fed us more and more back story. I took it to be crafted that way on purpose and found it interesting, not confusing or frustrating.

That’s the first I’ve read of your work, Mike. I like it very much. I am immediately reminded of Louise Erdrich’s story “Saint Marie” from her novel Love Medicine. Readers should approach “difficult” chapters as they do any other art. There are lots of “difficult” artists. Hieronymus Bosch. Van Gogh. Dante. The list is interminable. ReJoyce that you’ve been hallowed to join tHim.

I think I actually like those chapters–they make me think a lot about the story, and make me want to read more. I think they even make me read faster sometimes!

In writing, I tend to write entire shortstories leaving out details and leaving things to the readers’ imagination (that’s admittedly different than “difficult chapters”, but I think it’s similar enough to mention). But I’m not a very good writer yet, and probably don’t do the best job. But it’s still fun to do.

Didn’t find chapter 3 difficult. Maybe it’s just that the readers are used to different types of stories or writers. That means you are infiltrating a whole new audience.