Of all writers, you’d think that Christian ones would have a handle on God. But you’d be wrong. Especially as it relates to writing fiction. Notably of the speculative variety.

Of all writers, you’d think that Christian ones would have a handle on God. But you’d be wrong. Especially as it relates to writing fiction. Notably of the speculative variety.

It starts with the question — What is the defining trait of “Christian fiction”?

Ask that question to a dozen evangelicals and you’ll probably get a different answer. This article at Library Journal defines the genre by its “focus on biblical values and traditionally low emphasis on profanity, sex, or violence.” Another author defines Christian fiction as adhering to the following three criteria:

- The author avoids the use of graphic sex/violence and foul language.

- The story is based on Biblical teachings or relays the author’s beliefs.

- Whether the book is a mystery, science fiction, or based on historical facts the author is a Christian.

Whether a combination of the above or some variant, the definitions usually appear squishy. One trait that’s often mentioned when discussing the defining characteristics of fiction written by Christians is an accurate, biblical portrayal of God. If anything, they say, when Christians depict God in their fiction, they should do so accurately. While such a desire sounds noble, it’s in teasing out the details that we run into problems.

This is especially exacerbated if one is writing in the speculative genre.

In his article, Oh God, You Goddess?? Portraying God in Christian Speculative Fiction, author Tony Breeden explored the issue of how Christian writers should handle the creation of deities in their speculative stories. Breeden believes that while Christian authors are free to speculate, they must curtail speculation about the nature of God.

Speculative fiction is built on asking, What If? What if there were faeries? What if we colonized the moon? What if my math teacher is a werewolf from the Amish sector of Mars? A spec-fic author can speculate about a great many things including God, but a Christian spec-fic author must needs write the truth about God. In other words, God isn’t a What If. He’s the I AM. The God of the Bible has revealed Himself and changes not.

…Our first obligation as Christian spec-fic authors is not simply to ask “What If?” about anything and everything. Our first obligation is to glorify God through great storytelling – and we cannot do that if our storytelling contradicts the Bible’s revelation!

While this perspective is probably shared, at least in spirit, by many religious authors, the devil’s in the details. Breeden illustrates this as his article is in response to a debate about female deities and whether creating a female deity is outside biblical parameters Christian.

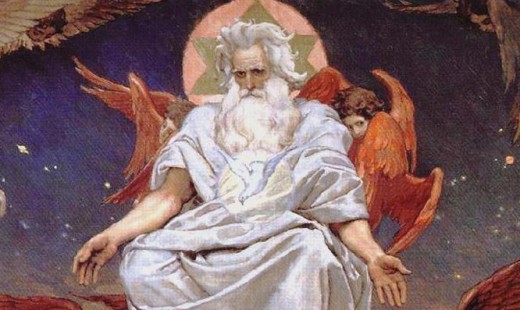

As I noted to those who said God is a Spirit and therefore genderless, one can only make that claim if they do not consider the context of the rest of Scripture, which overwhelmingly describes God as male. So, yes, God is a Spirit; he’s a male Spirit. (bold in original)

So in Breeden’s case, an accurate portrayal of God in fiction must be as a male. He summarizes,

One could be a Christian and write speculative fiction that asks What if God were female on some other world, but it would not be Christian spec-fic, for it does not speak the truth about God.

I use this as an example, not to debate the possible gender (or genderlessness) of God, but how the applied template can be problematic. This approach, in my opinion, is representative of the problem of demanding a “biblical” portrayal of God in our fiction. And as speculative fiction involves, um, speculation, the idea of any parameters can become rather sticky.

Let me cut to the chase. I don’t think the question for the Christian author is, Should any biblical parameters inform our fiction? But rather, How exacting, extensive should the enforcement of those biblical parameters be?

As I mentioned in my article No Zombies Allowed! (in Christian Fiction), believers can go to incredible length to impose theology on a story. It often leads to hairsplitting about whether we can justify a biblical basis for zombies, dragons, vampires, time travel, fae, etc., etc. Which is why it’s fairly common to find a Christian author spanking his or her story into biblical submission. As I wrote,

Forcing fiction to neatly fit your theology is a losing proposition

Please don’t interpret me as suggesting that the Christian author should be theologically indifferent or blatantly reckless. I recall once being involved in an online Skype chat session with some other authors and I suggested that the Christian author MUST operate within some biblical parameters, to which one of the panelists objected. To which I responded, “So the Christian writer should be free to write erotica?” Which, I think, made my point. Frankly, the Christian author who says there should be no parameters to speculation and content has a problem.

Anyway, so here’s some questions that always arise (in my mind) when Christian authors talk about portraying God in fiction (especially speculative fiction), followed by some brief thoughts:

- What constitutes a biblical portrayal of God in fiction?

- How does that distinctive practically reveal itself in a fictional setting?

- Is it even possible in the context of a single novel to accurately do so?

God’s character and nature is such an immense subject. My initial reaction when an author proclaims that “Our first obligation is to glorify God through great storytelling – and we cannot do that if our storytelling contradicts the Bible’s revelation!” is to ask what constitutes a realistic, biblical of portrayal of God? That may seem like hair-splitting. But unless you’re actually showing God in the flesh or doing something (through a vision or divine revelation), you’re pretty much consigned to showing Him through flawed characters, much like the Bible. (This would be compounded if those characters aren’t actually human. I mean, can you portray God through an atheist, an extraterrestrial, or a cyborg? Or can accurate portrayals of God only occur through human believers?) Which leads me to ask, can you ever accurately portray God through ANY characters?

Furthermore, a realistic portrayal of God is not always edifying, encouraging, or enlightening. In the Book of Job, watching Job’s family and property be systematically ravaged is part of a realistic portrayal of God. In the Book of Genesis, witnessing the horrors of the Flood is part of a realistic portrayal of God. The slaughter of firstborn Egyptian males reveals the character of God, as does the Red Sea, the Jewish wandering in the wilderness, and their exile into Babylon. King David revealed the nature of God… just not when he committed adultery and murder. Solomon showed forth God’s wisdom… until his concubine stole his heart. Point is, a realistic portrayal of God could leave one angry, perplexed, and un-inspired. When we think about accurate portrayals of God, are we simply thinking about His “positive” attributes?

Also, does any one action or picture of God accurately reflect His character and nature? Even if God is “male” (to use the above argument), does this mean His character and nature cannot be accurately portrayed through a female character or deity? Especially in speculative scenarios, we are pulling from races, customs, and genders outside of the norm. In other words, if we apply the “biblical” template too strictly upon our fiction, no genderless characters can ever accurately portray God.

Is it possible for a single work of fiction to accurately depict God’s nature or any one (much less all) of His attributes? He is merciful, holy, infinite, just, compassionate, omniscient, omnipresent, loving, gracious, etc., etc. So where do we start in our portrayal of God? And if we resign our story to just highlighting one attribute of God, we potentially present an imbalanced view (like those who always emphasize God’s love and not His judgment). Furthermore, we have the luxury of the Bible and centuries of councils and theologians to help us think through this issue. But when we bring this body of info to bear upon our novels, we must remember that others often don’t possess such detailed revelation… including our characters. Oceans of ink has been spilled dissecting the nature and attributes of God. So how in the world can any one book — biblical or fictional — ever hope to accomplish this?

All that to say, I think Christian speculative fiction has a God problem. In a way, it’s a good problem. At the least, we believe in God-revealed Truth. And we believe it should inspire us and inform our storytelling. Problem is, Christians hate to suffer ambiguity. The idea that someone might read our story and come away believing something “unbiblical” is anathema. As a result, we incorporate a theological checklist to our stories that inevitably stifles fictional worldbuilding and quenches creative speculation.

I don’t think the question is, Should any biblical parameters cordon our fiction? But rather, How exacting should the enforcement of those biblical parameters be?

Mike, you always draw me out of my cocoon when you write about this subject because I’ve had writer’s block for years in my spec fiction sequel of “Weep Not for the Dead.” It’s this kind of God-problem that has me stumped.

Since God uses countless avenues to reach the lost in this world, how would He reach the lost on another world? Would Christ’s sacrifice on this world suffice on another world? Why would God sacrifice His Son again on another world of sinners? In fact, the Bible says that Satan’s domain is this world, so how could he influence a different world?

Of course… it is fiction, so why do these questions bother me so much?

As to the other points, there is a book written by Joseph W. Smith called “Sex and Violence in the Bible.” An eyeopening read. I think it is “blunt but not gratuitous”, which is in the about section for the book. The Bible is blunt about many bodily functions and violence, but graphic descriptions are never indulged.

I think Christian authors should do the same. Sex and violence are part of the human stage and often drag a believer into muck. They should not be taboo subjects, but they should not be gratuitous. In other words, we should not glorify the sin.

Gina brings up a good point, one I have tried to address in the second sequel to A Dream of Dragons – Would Christ’s sacrifice on this world suffice for another? I believe yes because the Bible says Christ died once for all creation. I believe that means ALL creation. But how does another world find out about Christ? That is where I start in Book 2 – reaching out to other worlds to bring the gospel. There are an infinite number of possibilities for how that can be done – which leaves me with an infinite number of sequels that can be written. I agree sex and violence are part of the human condition and for a story to be true, it may need to be there in an honest telling that does not glorify the sin but lifts up the sinner for grace.

Gina, I think you’re asking the right questions. I’ve seen it explored a couple different ways by believers. One question I’d ask is, How has your storyworld fallen? Was it the result of Adam and Eve’s sin — which, if that’s the case, they are immediately tethered to earth in some symbiotic fashion — or did they have representatives of their own race like Adam and Eve? Answering those questions could help move you closer toward a resolution. I’ve seen this answered two basic ways: First, by framing the fallen race as simply part of the “Great Commission,” those in need of the Gospel and looking to earthlings as “missionaries.” (I believe the novel “The Sparrow” approached it from this angle. I might be mistaken.) The second approach would be to frame the world as un-fallen (ala, Lewis’ “Out of the Silent Planet” and “Perelandra”), and develop its own Creation / Fall / Redemption history. If that’s the case, and we prescribe to the belief that Christ died only “once for sins,” then His death on Earth would be the answer, UNLESS you can creatively conjure a way to “import” that Earth event into the extraterrestrial’s experience (a time travel event, a parallel universe intrusion, or an actual visitation from the risen Christ). Anyway, I think it’s good you’re thinking deeply through this.

Gina,

I recently wrestled with this issue and came up with the following response: http://tonybreeden.blogspot.com/2015/10/can-aliens-be-saved-or-extraterrestrial.html

Until we reach The Last Door,

Tony Breeden

This is a debate we chase around and around, as Christian authors. Do people in other religions do this? Like do Mormons debate how Mormon to make a story? (I can hear Brandon Sanderson laughing in the distance …)

As a reader, I dislike reading people anthropomorphizing God. It gives me an exact snapshot of their personal walk (or lack thereof), and makes me hugely uncomfortable. I’m fine with characters living out their faith. That’s fertile grounds for conversation about various aspects of faith and service, and whether Aslan accepts deeds done in the name of Tash. Just don’t show me a Jesus-figure. I dislike and avoid them.

This is such a key paragraph: “Problem is, Christians hate to suffer ambiguity. The idea that someone might read our story and come away believing something “unbiblical” is anathema. As a result, we incorporate a theological checklist to our stories that inevitably stifles fictional worldbuilding and quenches creative speculation.”

I often feel the responsibility to do everything in a story, all the way from planting a seed to harvesting it and planting the next one. When I feel that responsibility, my writing does become that “theological checklist” that must take a reader through all steps of the Roman Road. Perhaps some stories need to go through all those steps, but only if the story and the Lord lead me there. The mere assumption that all of that is our responsibility doesn’t trust the Lord to guide our readers, to still lead them well even if they do come away “believing something ‘unbiblical'”. That thought is very freeing to me, and removes the checklist from my writing.

Exactly. If the people who heard Jesus speak and, before then, the people who spoke with God came up with weird ideas as to God’s nature and character, why do we think we can write books that make such things impossible? Adam, who walked with God every evening was afraid of God after his first sin – if he knew firsthand how good God is, why did he think he needed to protect himself from God? And, while Jesus was on Earth, he read the exact same scriptures the teachers of the law did, and yet came to a very different conclusion than they did about God’s heart for people. Nowadays, people will read the Bible and come to the conclusion that God doesn’t exist.

What we write offers possibilities to our readers. Opportunities for either life or death. But the path they choose is ultimately up to them and where they decide truth lies. We can’t make that choice for them, and it’s patronizing to write books as if giving a ballot card with only one option on it – that’s what a totalitarian regime intent on controlling its populace does to justify its reign. Love must be freely chosen, or else God wouldn’t have created the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil.

Hi Mike!

Love your posts, and as usual you present both sides of an argument and make a well thought out conclusion.

As for me and writings. I am unsure whether I would classify them as Christian fiction. I am a believer in Christ, but my books may not be classified as such. Scratch that- my poetry is religious. My fiction is something else altogether but it many cases it does depict God as I think He is.

I just want to tell a good story. If I consider that God is in me, then whatever I write, He will be exposed to the world through those words anyway.

Great discussion!

We are finite creatures. Therefore, we cannot define nor relegate only certain characteristics to an infinite creator.

Nor should we try.

I have not yet solved the “God problem” in my own writing, but this is definitely something to think about. I believe C.S. Lewis himself even denied that his notorious Aslan was a straightforward symbol of Jesus; he was only a “type” of Jesus…probably because of these very reasons you bring out, Mike. Christian authors feel they have to recreate God as entirely God in their fiction in order to do Him justice…

But we don’t even do Him justice in our every day lives. How in the world do we expect to in our fiction?

Just some off-the-cuff thoughts. Great article; thanks for posting!

Not all Christians agree on God’s character. That’s a major issue.

I for example have slowly become a Universalist from my careful study of Scripture.

The problem with the God problem is it expects Christian authors to define God like a theological book would. All a novel can really do is reveal God working in people’s lives and the varied understandings about God, right or wrong, they might have. If everyone believes the same in a book, or only have two categories (believer and non-believer), it greatly limits character building and character arcs. God can only be shown in a novel, not defined, and even that imperfectly considering He’s infinite and we’re finite, and our novels are written by a finite author.

Of course, that does make for a lot of ambiguity. On our side of creation, God often doesn’t make sense or seems capricious, but that doesn’t mean He is. It’s just our experience of Him. But to be true to the nature of God, there is a sense that our fiction needs that ambiguity about God, not only so we don’t define Him wrongly (most heresies are based upon trying to define a paradox of God that should be left ambiguous), but so we’ll be true to the human experience of God and through that, show who God is, not tell people who God is.

That’s how Jesus did it. He told parables that many people didn’t get. Didn’t see the truth He was teaching, and Jesus was okay with that. He gave it for those who would see the truth through it because they had eyes to see and ears to hear.

That’s how I approach it, anyway. Let God use our words to teach truths He wants people to see and hear. Our job is to tell a good story and give God the opportunity to use it for His glory.

“So the Christian writer should be free to write erotica?”

Yes. Song of Songs is in the Bible. And no, it’s not all allegory and metaphor.

Simon, so would you be saying that Christian authors should have NO content restraints?

Christian authors should have only the constraints they put on themselves: there should be no external pressure (or expectation) that they should behave in a certain way. I certainly struggle with some of the dark paths I end up going down, and sometimes my internal censor kicks in with a big fat ‘nope’.

But the story is the story. If the story is strong meat, yet the author consistently pulls their punches when writing it down, they have two choices: go with it, or give it up. Not all stories need to be told, but those that are, need to be told well, with all the artistic skill the author can muster.

And on the specific point: why do we find it so much easier to write a scene where two people are trying to kill each other, as opposed to making love? What’s the ‘Christian’ answer to that?

“Christian authors should have only the constraints they put on themselves: there should be no external pressure (or expectation) that they should behave in a certain way.”

Ditto, we’re not under The Law.

We are to love God and people. That is, we are to value, prefer, hold in high regard, and have goodwill for God and people. That sums up the entirety of the law and the prophets, and that sums up God’s person, character, and motives.

The question, in my mind, is less “should we have parameters?” because we’ve already been given *the* parameter: love. And a whole Bible to show us what that looks like. In my mind, the more fruitful question is “how do I write out of my love for God and people?”

Some people can see no way to include swearing in their novels from the motivation of love. Others can. Some can see no way to talk about magic or worlds where God isn’t mentioned and have it be from the motivation of love. Others can.

This whole topic isn’t going to be solved by setting corporate regulations on Christians, whether those regulations are loose or tight. But it will be lived out well when we all take responsibility for being disciples of Christ and walking with him as we mature in love.

After all, it says in 1 Samuel 16:7 “Man looks at the outward appearance, but the Lord looks at the heart.” All of this comes from the heart, and so the heart is where we must address it. But, while we can talk about the heart, we can never address anyone’s heart but our own. Not even God, in his perfect love, will violate our hearts. He will knock, certainly, but we have to decide to let him in.

So while this kind of talk can be intellectually stimulating, I don’t find it useful for empowering us create the kind of art we’re inspired to create, because all it talks about is new ways of changing people’s behaviour without having to nurture their hearts.

“So the Christian writer should be free to write erotica?”

My exact thought upon reaching that point in the post was, “Does his Bible jump straight from Ecclesiastes to Isaiah?”

I think defining parameters by “good” or “bad” content is asking the wrong question. That’s a disservice to both art and Scripture.

Content should be constrained by its theme and purpose, not by cultural norms — and yes, comfort levels with various bodily processes, whether procreating or defecating or destroying or degenerating, are largely cultural. Several times and places in history have viewed layered clothing as decadently erotic because nudity was the cultural norm, for example, or happily shared group baths or toilets, while today in the West we generally feel the opposite.

Erotica for the sake of glorifying anonymous or detached sex is not representing a Biblical view. A celebration of physical love as a manifestation of intellectual, emotional, and even spiritual love can be well within a Biblical view. Now, there’s no reason to include such a scene if the story doesn’t require it — but if the story does, then how can we say that sex is not a “Christian” topic? Is every single screaming baby in the Sunday morning nursery adopted into a white marriage?

Oddly enough, my own work probably falls within many artificial parameters, whether because of my own cultural norms or story preferences, but I would not argue that standard for other stories, just because it’s my own. I may have personal preferences about what I like to read, but that doesn’t mean that what I dislike is unChristian. I think the theme of a scene is far more important than any particular word used or act depicted. Murder, for example, is fairly unChristian, and yet shows up in many “Christian” books.

The problem is that we’ve confused “Christian” and “clean” into a single publishing category, and the Bible is full of the unclean who were made clean.

Overall, a good post and thought-provoking! (Side note: I’m sure this was an unintentional accident of grammar, but I’m pretty sure there are human atheists on this planet. 🙂 )

Mike,

I don’t think you’ve painted my views at all fairly in this post, and you’ve certainly not engaged my argument. After all, I’ve written about super-powered teens at a keg party [one of the settings of Johnny Came Home] and an alien world that is terraformed precisely so folks can play a live-action version of an AD&D/Warcraft-styled game. I color well outside the lines of man-made traditions, but not beyond the borders God has revealed in His Word.

We both agree that a line must be drawn. The trouble is that you clearly think the fence that God has provided to keep us from falling off the cliff on the other side is too restricting to your creative freedom because a horse is meant to run, amen, and you can’t run in that direction because of that fence.

I think my parable is clear, but just to be certain, let me add this: You are fond of quotung yourself as saying, “”Forcing fiction to neatly fit your theology is a losing proposition… at least, if creative storytelling is your aim;” however, as I noted in another post you’re mentioned in [http://tonybreeden.blogspot.com/2014/07/what-is-christian-speculative-fiction.html], what you’re suggesting in that quote is that “our primary objective should be good storytelling – and that would be true if we were merely authors – BUT as Christians our primary goal is to glorify God through good storytelling… and we cannot do that if we do not chain ourselves to the Word of truth. Twice in his first epistle to the Corinthian church, Paul says that all things are lawful (permissible) to me, but not all things are expedient. [I Cor 6:12; 10:23]. Underline that truth. Just because you can, doesn’t mean you should. God, by definition, is the I AM. To put it another way, He is The Way, The TRUTH, and The Life. God is NOT a What If? We do not get to play god with God’s identity and attributes without also creating a non-Christian god… and how could that be considered Christian fiction in any sense?”

At best, we could call it, fiction by a Christian, but it would be inaccurate to characterize it as Christian fiction.

Likewise I take issue with your insinuation that making our fiction conform to our theology necessarily limits our creative storytelling. I’ve reviewed many Christian spec-fic novels that managed both nicely. In fact, I would defy you to pick up one of my books and see how well your truism holds up to reality. There’s a whole genre of storytelling called apologetics fiction that makes nonsense of your regrettable quote.

Until we reach the Last Door,

Tony Breeden

Mike,

I don’t think you’ve painted my views at all fairly in this post, and you’ve certainly not engaged my argument. After all, I’ve written about super-powered teens at a keg party [one of the settings of Johnny Came Home] and an alien world that is terraformed precisely so folks can play a live-action version of an AD&D/Warcraft-styled game. I color well outside the lines of man-made traditions, but not beyond the borders God has revealed in His Word.

We both agree that a line must be drawn. The trouble is that you clearly think the fence that God has provided to keep us from falling off the cliff on the other side is too restricting to your creative freedom because a horse is meant to run, amen, and you can’t run in that direction because of that fence.

I think my parable is clear, but just to be certain, let me add this: You are fond of quoting yourself as saying, “”Forcing fiction to neatly fit your theology is a losing proposition… at least, if creative storytelling is your aim;” however, as I noted in another post you’re mentioned in [ http://tonybreeden.blogspot.com/2014/07/what-is-christian-speculative-fiction.html ], what you’re suggesting in that quote is that “our primary objective should be good storytelling – and that would be true if we were merely authors – BUT as Christians our primary goal is to glorify God through good storytelling… and we cannot do that if we do not chain ourselves to the Word of truth. Twice in his first epistle to the Corinthian church, Paul says that all things are lawful (permissible) to me, but not all things are expedient. [I Cor 6:12; 10:23]. Underline that truth. Just because you can, doesn’t mean you should. God, by definition, is the I AM. To put it another way, He is The Way, The TRUTH, and The Life. God is NOT a What If? We do not get to play god with God’s identity and attributes without also creating a non-Christian god… and how could that be considered Christian fiction in any sense?”

At best, we could call it, fiction by a Christian, but it would be inaccurate to characterize it as Christian fiction.

Likewise I take issue with your insinuation that making our fiction conform to our theology necessarily limits our creative storytelling. I’ve reviewed many Christian spec-fic novels that managed both nicely. In fact, I would defy you to pick up one of my books and see how well your truism holds up to reality. There’s a whole genre of storytelling called apologetics fiction that makes nonsense of your regrettable quote.

Until we reach the Last Door,

Tony Breeden

Thanks for commenting, Tony. Let me challenge two of your points. You wrote:

“We both agree that a line must be drawn. The trouble is that you clearly think the fence that God has provided to keep us from falling off the cliff on the other side is too restricting to your creative freedom…”

Okay. What is “the fence that God has provided” for writing fiction? If we’re talking theology and doctrine, I think I know what that “fence” is. If we’re talking morals and ethics I think I know what that “fence” is. But if we’re talking about art — whether painting, carving, acting, filmmaking, or novel writing — what is “the fence that God has provided” for art? You’ve answered that, at least as it relates to depictions of God, in terms of explicit theological alignment. As I’ve laid out in this post, I believe that’s incredibly nebulous. Can we present an articulate, theologically sound portrayal of God through flawed or antagonistic characters? Even in the Bible, no one book perfectly represents the image of God. So how can one of ours? What if my story IS about a failed false deity? Must I articulate that in order to be theologically approved? Frankly, this is why some define the theological “fence” for fiction as occupying more conservative boundaries like “no cursing” or “no sex” or “no violence” or “no zombies” or no “superpowers.” We are supposed to glorify God in EVERYTHING we do — housework, homework, office work, athletics, diet, grooming, money management, etc., etc. Unless you believe that that means articulating the gospel EVERYWHERE and in EVERYTHING (not sure how I’d do that cleaning my office or bathing), I believe there’s lots of room for nuance.

Secondly, you wrote, “I take issue with your insinuation that making our fiction conform to our theology necessarily limits our creative storytelling.” I think this is an indisputable truth for those who adhere to some definition of “Christian fiction.” Indisputable. I’ve been debating this for almost a decade now. While some will argue that you actually have to be MORE creative to get around the censorship of our content, the fact that Christians regularly argue that things like zombies, vampires, dragons, spells, witches, alternate histories (especially concerning biblical characters) are off-limits. You may disagree with them. That’s fine. The point is that approaching fiction with a strict eye to theology will inevitably influence how far we go with our stories. As I said, that can be both a good and a bad thing.

Once again, I appreciate your writing. I believe this is a debate worth having. Blessings!

Mike,

I think that you need to understand two things about me as we debate this: Firstly, I do not always agree with you but I do admire you. Secondly, I come from both sides of this debate. As both a preacher/apologist and a spec-fic author, I have kind of a unique perspective on this.

Now, as I mentioned to one of your commenters on Facebook, it is a preacher/theologian’s job to comment on how Scripture’s teaching applies to our everyday lives and occupations. The theological lines are clear; pretending as if they do not or should not apply to our trade (a written form of communication) is dissemblance.

I mentioned apologetics fiction as one clear example of spec-fic that defies that favored quote of yours, but I’ve read Christian fiction that wasn’t quite as overt. For example, when I wrote Luckbane I only included one God moment, a reminder that my protagonist was a nominal Christian, but the major themes of the book are still consistent with a Christian worldview. So when you object that flawed humans and no single book of Scripture conveys God in full, I laugh. Where God is concerned, we see in part, through a glass darkly; a full view would be too much. Nevertheless, we do have a fuller revelation of all of Old and New Testament Scripture, so I do not think God will wink at us as if we only had one book; still, there is a lesson here and the lesson is this: we do not have to reveal all of God or all of doctrine in our writings, but what we write must not contradict what His Word has revealed. It must be consistent with revealed truth. If your world of elves and orcs worships a true God [false deities are irrelevant to the question precisely because they are not God at all], what we reveal of that true God should be consistent with what God has revealed of Himself.

The real problem here isn’t a God problem; it’s an authority problem: whether our master as spec-fic authors is pure unfettered speculation or the Bible. That sounds rather heavy-handed, but I find it hard to argue that this distilled argument is inaccurate. God has provided a fence for art; that we do all things for His glory and as if unto Him. That being the case, how can we write spec-faith that inaccurately portrays the One we are meant to be writing for. God is our ultimate audience, which is fitting since he is revealed to be the Author and Editor of our faith! It is all for Him or it is all for nought.

Until we reach the Last Door,

Tony Breeden

What we have here

Tony, again, this definition is incredibly nebulous and offers little clarity to Christians artists approaching the “God question.” Before I continue, I want to add that I too am an ordained minister, was a full-time staff pastor, still preach on occasion, and am very interested in apologetics. That said, I’m not approaching this subject as a complete layman.

Like you, even my stories that are not explicitly “Christian” contain “major themes… consistent with a Christian worldview.” Nevertheless, I’ve still had some question my theology (and have even been called a heretic a couple of times). You wrote, “we do not have to reveal all of God or all of doctrine in our writings, but what we write must not contradict what His Word has revealed. It must be consistent with revealed truth.” I pretty much agree with this. The problem is, How literal, how articulate, how detailed, how explicit must that fictional “consistency” be? This is where believers constantly clash.

If we simply zero in on depictions of God, so many things come into play — the POV of the character, the attribute of God being highlighted, the amount of detailed information about God being discussed, illustrated, or disseminated, etc. For example, say my story is about a person that worships a false god (perhaps an Ungot-like god from Lewis’ “Till We Have Faces”) and my intent is to show the attributes of the real God by simply showing the empty religion of Ungot-worshipers. On its face, Christians could rightly consider such a story heretical because it is not “consistent with what God has revealed of Himself.” Of course it’s not! It’s not intended to be. And that’s my point. Every character will come at God from a different angle. Some will portray Him accurately, some inaccurately, and others only partly accurately. My goal as an author is not to take a reader by the hand and walk them to some theological conclusion. Another example could be Flannery O’Connor. She was an outspoken Christian author. Nevertheless, her fiction is rarely considered “Christian fiction” even though she writes often about “Christian worldview” themes. Grotesque and wretched characters like Hazel Motes or the Misfit reveal God in startling ways, nevertheless those characters can be easily misinterpreted. Which O’Connor’s fiction often was. The point being, while the author may have an orthodox belief about God, his characters always don’t. Demanding that his characters also embrace and articulate his orthodoxy moves way out of the realm of storytelling and into propaganda.

Mike,

What exactly do you find nebulous about it? Perhaps you’re misunderstanding where my objection lies.

When I wrote that we do not have to reveal all of God or all of doctrine in our writings, but what we write must not contradict what His Word has revealed, I meant just that. It must be consistent with revealed truth.

I suspect a misunderstanding because you’re bring up red herrings like false deities and a character’s understanding of God. Deities that are revealed to be false in the novel are irrelevant to the point; the problem arises when we don’t identify them as false gods somehow. No one’s demanding that an author’s characters embrace and articulate his orthodoxy; that’s a rather wooden way of looking at my position and its a bit of a straw man. Obviously, different characters will obviously have different views about God, but any author worth their salt, Christian or otherwise, generally finds a way to let the reader know which view is correct. That’s not what we’re talking about here.

The trouble is that there are some Christian authors who hold to a view that may be described as Scriptura sub speculativa (“Scripture under speculation”), or at least Prima speculativa; that is, the Bible’s revelation is a secondary consideration to speculation where fiction is concerned. This ought not be so. I can’t help wonder if it isn’t a knee-jerk reaction against the unrealistic restraint of CBA/ECLA standards that makes Christian speculative authors wary of being held to ANY standards, but if we cannot submit to a minimal standard wherein we accurately portray God when we are describing the One true God in our fiction, what else are we but rebellious children posturing as edgy?

Paul warned Timothy to “instruct certain men not to teach strange doctrines, nor to pay attention to myths and endless genealogies, which give rise to mere speculation rather than furthering the administration of God which is by faith.” [1 Timothy 1:3-4] The principle we can glean from this verse is that speculation is never meant to take precedent over doctrine.

Having said that, what we are talking about here is portraying a deity in your fiction as if they represented the Biblical God but who differs from what the Bible reveals about Him in a meaningful way. For example, if your book’s elven deity Primus is clearly the true God of your story and you decide Primus is female, the takeaway for the reader is that feminist revisions of the Bible are acceptable. In this case, you’ve crossed the line from asking “What If?” to “Did God really say?” (a question more generally associated with the most devastating moment in human history) because you’re not just telling a story that gender flips the I Am, you’re doing so in defiance of the Bible’s repeated revelation that God is masculine… for the sake of a story, for the sake of the speculative aspect of our craft.

The line is clear. Prima speculativa simply wishes it wasn’t because they do recognize that the Christian part of Christian speculative fiction should limit them somehow. CBA/ECLA standards can be likened to the man-made prohibitions of the most caricatured stripe of fundamentalism. We note how, not only were their rules Pharisaical, their children had this tendency to run as far and as fast as they could once they turned 18! Sadly, the anecdotal evidence suggests that a great many of them ended up like me (or worse in cases where prodigals did not eventually come home!) and went way too far in the other direction.

All things are permissible; not all things are expedient. All things are permissible; but not everything edifies [1 Cor 10:23]. Let’s not pretend our fiction honors God when we’re painting funny glasses over His portrait.

Until we reach the Last Door,

Tony Breeden

P.S. Mike, I said that I admire you, which means that I am familiar with your background as a minister. I merely wanted to remind you that I come from a similar situation. No insult or slight was intended by the comment.

Tony, you’re not engaging my point. This paragraph pretty much sums up the crux of our disagreement:

“I suspect a misunderstanding because you’re bring up red herrings like false deities and a character’s understanding of God. Deities that are revealed to be false in the novel are irrelevant to the point; the problem arises when we don’t identify them as false gods somehow. No one’s demanding that an author’s characters embrace and articulate his orthodoxy; that’s a rather wooden way of looking at my position and its a bit of a straw man. Obviously, different characters will obviously have different views about God, but any author worth their salt, Christian or otherwise, generally finds a way to let the reader know which view is correct. That’s not what we’re talking about here.”

I’m unsure why you’re framing my rebuttals as “red herrings” and “straw men.” I think they speak directly to your point. When you suggest that “Deities that are revealed to be false in the novel are irrelevant to the point; the problem arises when we don’t identify them as false gods somehow,” you are speaking directly to our disagreement. While we both agree that Christian authors are free to write about false deities, we disagree about whether those same authors must “identify them as false gods.” That’s it. That’s the basis of our disagreement. You believe that “any author worth their salt” must find a way “to let the reader know which view is correct.” I don’t believe this. I don’t believe the author’s job is to clarify theological nuances. I don’t believe that Lewis needed to spell out how Ungot was not the true God. I don’t believe O’Connor needed to articulate if Hazel Motes actually became a Christian (which is often debated). It is precisely in the articulation and spelling out of these theological details that I believe Christian spec-fic’s “God problem” exists.

Mike,

Actually I think that any author worth their salt does find a way to let the reader know which way is correct. In Till We Have Faces, Lewis took the myth of Psyche and Cupid and retold it as a Christian myth or allegory. In this tale, Psyche is a type of Christ, the sacrificial substitute for her beloved Orual, and also a type of Ecclesia, the beloved of the God of the Mountain. Just as we are imputed the righteousness of Christ and become a part of His Body, Orual is told repeatedly that “You too shall be Psyche,” though she does not understand what this means until the end. By relational context, the God of the Mountain is the One True God that is analogous to the Biblical Jehovah God in this story. Not Ungit. Ungit is worshipped as a goddess but she is never hinted at being the tale’s One True God, which is why I think of Ungit as a red herring to the discussion at hand. Allegorically speaking, she is sex and death, the Curse personified. Like all allegories (and I’m sure Lewis as a hair-splitting expert on allegory would object that his work was more supposition than allegory, but whatever), Lewis’ is imperfect, but the reader is not left thinking of her in a favorable light as we do regarding the God of the Mountain. It’s not spelled out, but we are led in a certain direction.

Regarding Hazel Motes… I have a scene in Johnny Came Home where a pastor is given a chance to try to convert a jaded soldier on his deathbed. He tells the pastor the attempt is pointless from the start and that he’s not even sure foxhole conversions should count, but he understands that preachers preach and soldiers soldier. The soldier never converts. The character may not convert but my readers know that the preacher has spoken truth. If we cannot clearly articulate truth in our writing, we may as well be preaching relativism. I mentioned another scene in Dreadknights where a young woman erroneously believes that the existence of aliens falsified the Bible. I never let the read know whether my protagonist comes to accept the counter argument of her friend, but the way I paint the scene makes it clear that he has spoken truth.

I don’t believe that we need to make our characters woodenly orthodox, which is why I think of Hazel Motes as a straw man. I have an entire essay on my site decrying plastic characters and sermons-in-a-blanket. I do think that when we’re describing a God who is allegorical, analogous or suppositional of the true Biblical God that we need to make sure we keep to the true revelation we’ve been given of Him.

If you still think I’m missing your point (very possible, given our discussion thus far; there seams to be a thread left unpulled that will finally rip this this thing wide open (pun intended)), give me a different example because I’m not seeing it in Hazel Motes and Ungit. It’s just not clicking.

Until we reach The Last Door,

Tony Breeden

While I would agree that certain lines must be drawn when a Christian writes “edgy” content and genres, I think that line would be “what honors God”.

True, the question of “what if” can lead an author and his reader pretty far afield, but I don’t think that we should limit our “what ifs”, even to the nature of God. Quite the contrary, I think God-honoring speculative fiction is the PERFECT place to explore all the “what ifs” that might be too controversial anywhere else.

What if Jesus was merely a man and not divine. What if God were female. When you write a story with the aim to HONOR God, consistency — following each “if” to its inevitable “then” — is bound to be a consequence. IF Jesus were merely human and not divine, THEN it would have this impact on salvation… which is why this “if” could not be a reality. That sort of thing.

These ifs and thens riddle our Bible. For Paul, it was his stock in trade, and it played a vital role in his ministry. “What then? If X is true, then is Y true? God forbid!” Paul made it his BUSINESS to ask “what if” — not to bring doubt, but to flesh out the consequence of each belief, and to hold that belief in INTEGRITY, in agreement with all other aspects of scripture.

My thoughts? “What if” your story to death, if that is what God has called you to do. No holds barred. Except, in presenting your question, it behooves you to not just ask “what if”, but to provide a consistent “then” for every “if”.

Jeremy,

We certainly ought to provide a consistent THEN for every IF statement [and the old programmer in me wonders if perhaps an ELSE would be helpful now and then], but consistent with what? The only answer we can come up that is consistent with the Christian faith is that the THEN [or ELSE] must be consistent with revealed truth [e.g., Christian doctrine/worldview].

Until we reach The Last Door,

Tony Breeden

Interesting post, Mike. I think we can all agree that the Christian author’s motive should be to glorify God in his/her writing and that we should never willfully contradict or undermine His revealed truth in order to exercise our own idea of “freedom”. Apart from that, though, I think much of it comes down to a matter of individual conscience, both for the author and the reader.

On an interesting side note, when George MacDonald (whose books powerfully influenced both Lewis and Tolkien) wrote his semi-allegorical fantasy novels for children such as the CURDIE books, AT THE BACK OF THE NORTH WIND and THE LOST PRINCESS, the characters who most represent God’s attributes in the story are women. In CURDIE it is the mysterious Queen Irene (who is a clearly supernatural figure in her power, her wisdom, and her seemingly endless life, and in the second book lays aside a humble disguise to reveal her true glory and then serves bread and wine to the other characters (!)) in ATBNW it is the North Wind herself, and in PRINCESS it is the Wise Woman. Yet there is nothing of pagan goddess-worship in the portrayals, or any commentary as such on gender and spirituality at all; the portrayals seem natural and inevitable to the story and are both reverent and thought-provoking. I would never have imagined it possible, and even (perhaps especially) as a woman I don’t know that I could pull it off myself. But MacDonald does it beautifully, and generations of Christians have read his books without feeling shocked or alarmed by that aspect at all.

R.J., I’m also seeming to reach the conclusion that this “comes down to a matter of individual conscience, both for the author and the reader.” I wish there were more concrete Scriptural truth to guide our fictional pursuits, but there just isn’t. Which is probably why so much of the debate comes down to what a person wants for and expects from the stories they write/read, rather than some set-in-stone biblical formula.

In a less literary way, The Shack did a similar thing.

I’ve constructed a more distilled response to this article here: http://tonybreeden.blogspot.com/2016/02/christian-speculative-fiction-and.html

Until we reach The Last Door,

Tony Breeden

Wow, Mike, you handled this conundrum so succinctly and wisely. And gave me lots to think about. I don’t generally write spec fic, but my work in progress has elements of – real world, but playing with historical events. Comment re God’s gender: The Shack portrayed one member of the Godhead (Holy Spirit, I think from memory ) as female. The effect was powerful and, to me at least, not in any way offensive.

This “God issue” is one reason I tend to lean towards urban fantasy rather than epic fantasy, or human-based sci-fi rather than aliens, with inborn magic explained as being part of genetic bottlenecking and such. (And then sometimes I do have plans for an alien sci-fi or three where aliens make good analogy.)

But I don’t write to preach the Gospel; my stories often revolve around how what the characters trust in and value affects their lives. My stories also tend to be dark. Not all my MCs are believers (nor will they be)—and some believers do “bad” things, and some unbelievers do “good” things. People are innately sinful, not innately good.

All these things are part of my point as a writer, tbh.

I am Christian. However, I can’t think of any of my work that would unequivocally pass the qualifications for Christian market fiction. The epic fantasy series can…but the faith’s in the background, not definitively Christian, and has some topics that some people prefer forgetting are in the Bible. The in-progress epic fantasy series is more overtly Christian, with an unapologetically Christian narrator, but…there’s some cursing and, again, topics that some people prefer forgetting are in the Bible.

Out of consideration for my readers, I do endeavor to put content alerts on my work, so those who want to avoid certain things can avoid it. I have one WiP where I may include a censored and uncensored version in the book file, because the narrator uses a lot of R-rated language, and there really isn’t any way to avoid it that won’t affect the core of the character and story—and his propensity for the f word is the least of his problems.

What my characters don’t use? Abuses of God’s name. I don’t allow taking of the Lord’s name in vain in my stories, though I may change my PoV on that someday.

I also don’t intentionally include erotic scenes, although my topics/themes/characters means there can be some tactful on-page nudity, etc. But I also have the gift of celibacy, and sometimes a beta reader alerts me, “Um, you might want to cut this phrase…”

But this is all my choice, based on my own theological convictions and prayerful consideration of Scripture. Other Christians will have their own convictions, which all our prerogative. There are things I don’t think Christians should write, but that’s something to discuss with others, not to demand of them.

There are very few things that I view as necessarily incompatible with Christianity, and those things have far more to do with the handling of sin rather than the inclusion of it—but even that doesn’t account for the possibility of satire or analogy/allegory.

What concerns me more is how people come up with some list of “rules” that all Christians must follow, else they’re not really being Christlike—every such list I’ve seen includes items that are actually in Scripture and therefore end up Pharisaical.

Is erotica best avoided by Christians? Probably. It can trigger self-insertive lust and/or voyeurism…er, right? I’m having to guess at the reasons, thanks to my gift of celibacy.

I seriously do not experience no sexual or romantic inclination whatsoever. Never have. (It’s been incredibly confusing, due to certain folks insisting I had to be feeling them, so I grew up with terms redefined based on what I was actually feeling, which was really confusing when folks were talking about their own crushes and whatnot. People make so much more sense, now that I have that straightened out.)

Pretty landscape, pretty painting, pretty person—it’s all the same to me. Graphic sex scenes are more likely to bore me or gross me out than to keep my attention.

When you don’t experience romantic interest, how do you recognize someone’s flirting in time to catch it early and let them down lightly? (You can’t.) When you don’t experience lust, how can you recognize immodesty? (You can’t. I used to hide myself in clothes a few sizes too big, since I can’t naturally tell the difference between something that fit and something that was “too” clingy. I’ve developed better definitions, but I still get second opinions.)

Reading some erotic books has proved helpful for me, as examples to help me get an idea of how most other people look at things and to analyze those things better, though it’s still a matter of memorized “rules” rather than an innate awareness of the concepts in themselves.

Would I write erotica? No. (The result would likely be pretty funny if I tried.) But I do see how Song of Solomon can be used to justify certain forms of erotic content.

Edit: “I seriously do not experience no sexual or romantic inclination whatsoever” should be “I seriously do not experience

nosexual or romantic inclination whatsoever.”Christian fiction? You don’t make fun of God.

Wow. Jesus telling parables was making fun of God, I guess. Looks like Jesus blew it big time. Thanks for the corrective, Roger.

God is neither male nor female.