I received a nice review of Saint Death over at the Black Gate (HERE). The reviewer mentioned something that I thought worth addressing — my depiction of Santa Muerte in the novel.

I received a nice review of Saint Death over at the Black Gate (HERE). The reviewer mentioned something that I thought worth addressing — my depiction of Santa Muerte in the novel.

Some might find Mike Duran’s handling of the Santa Muerte folk religion troubling. Since in his book it’s used as a front for summoning the archangel of death, he tends to play up the darker aspects, such as its association with drug dealers and criminals. This is not at all an even-handed approach, or an attempt to treat the religion fairly. But focusing on the darker aspects of religion has long been a useful tool for horror writers.

The reviewer is correct in that I used the religion “as a front,” fictionally speaking. But did I not offer “an even-handed approach” or “attempt to treat the religion fairly”?

Here’s my intro to Santa Muerte in the first chapter, spoken through the POV of Reagan Moon:

I’d seen them before, shrines like this. Usually they were accompanied by murder and mayhem. The Santa Muerte religion had been migrating from Mexico into the southland for the last half century bringing with it a toxic mix of old world esoterica, spiritualism, and crime. Its central deity was sometimes displayed as a Virgin, a bride, or a queen. Some called her the Grim Reapress, others the Bony Lady.

But mostly she was known as Saint Death.

Over time, she’d become the patron saint of drug lords and hit men; the Mexican cartel had adopted her as their own, splaying untold victims upon her altars. Saint Death’s protection and blessings were routinely sought, as was her vengeance. Whether one was seeking to guarantee safe passage of a drug shipment, smite a foe with the necrotizing fasciitis, or be protected from such curses, Saint Death was all ears.

Is this a fair summary? I think so. You see, the “darker aspects” of Santa Muerte are some of its primary attractions. For example, this Time photo essay is subtitled Mexico’s Cult of Holy Death. The folk religion is viewed as a “cult” for several reasons. As this National Geographic article notes, before its more recent mainstream appeal, Santa Muerte was “initially popular among people living in the underworld or on the fringes of society.” The religion’s connection to “underworld” elements, namely drug cartels, fueled Santa Muerte’s popularity. Finally, there was a “saint” for the marginalized, one that could both take vengeance and protect against vengeance-seekers. This Huffington Post article notes that “the very origins of the cult are tied to crime.” An article entitled Folk Saint Santa Muerte is Alive and Well in L.A. — Death, Devotion, and the DEA cites the FBI’s Behavioral Science Unit in describing Santa Muerte as a “new age Grim Reaper-type goddess, a bad-girl counterpart to the Virgin of Guadalupe.” Though the religion’s devotees are particularly growing among disenfranchised and/or disillusioned Catholics, it is narcocultura that fuels its spread.

Still, the strongest contributing factor to the stigma against the folk saint is her constant association with drug traffickers and the dark spirituality of narcocultura, or drug culture. With the high stakes of the drug trade, the offerings by cartel members to Santa Muerte can surpass the normal tokens of food and drink, and dip into the realm of human sacrifice.

It was this reality that sparked my interest in the religion. For one thing, this was happening next door to me! Stories about Santa Muerte related crimes began showing up. Like the discovery of human remains inside a residential altar in Pasadena, which immediately solicited question about Santa Muerte. Or in Oxnard where authorities discovered a human skull and jawbone, along with a discarded Santa Muerte altar. Then there were incidents of actual human sacrifice to the Saint of Death. It was reported that more L.A. prison inmates were sporting Santa Muerte tattoos and that Santa Muerte was gaining a following among major criminal organizations. It’s even led to L.A.’s DEA division creating a number of continuing education classes which focus upon the religion.

It was this reality that sparked my interest in the religion. For one thing, this was happening next door to me! Stories about Santa Muerte related crimes began showing up. Like the discovery of human remains inside a residential altar in Pasadena, which immediately solicited question about Santa Muerte. Or in Oxnard where authorities discovered a human skull and jawbone, along with a discarded Santa Muerte altar. Then there were incidents of actual human sacrifice to the Saint of Death. It was reported that more L.A. prison inmates were sporting Santa Muerte tattoos and that Santa Muerte was gaining a following among major criminal organizations. It’s even led to L.A.’s DEA division creating a number of continuing education classes which focus upon the religion.

“Here in L.A. you become very much aware of it as soon as you start working in investigations,” says Sarah Pullen, Public Information Officer for the Los Angeles DEA division. “Investigators know about it, and it’s covered in a number of continuing education classes.”

Despite the growth and popularity of the folk religion, the Catholic Church has officially not recognized Santa Muerte with legitimacy. On May 8, a high-ranking Vatican official made what amounts to the Catholic Church’s first public statement regarding the cult.

“It’s not religion just because it’s dressed up like religion; it’s a blasphemy against religion,” said Cardinal Gianfranco Ravasi, president of the Vatican’s Pontifical Council for Culture.

It isn’t the Vatican’s habit to give its opinion on every passing cult that flashes across the horizon, but the Santa Muerte is special.

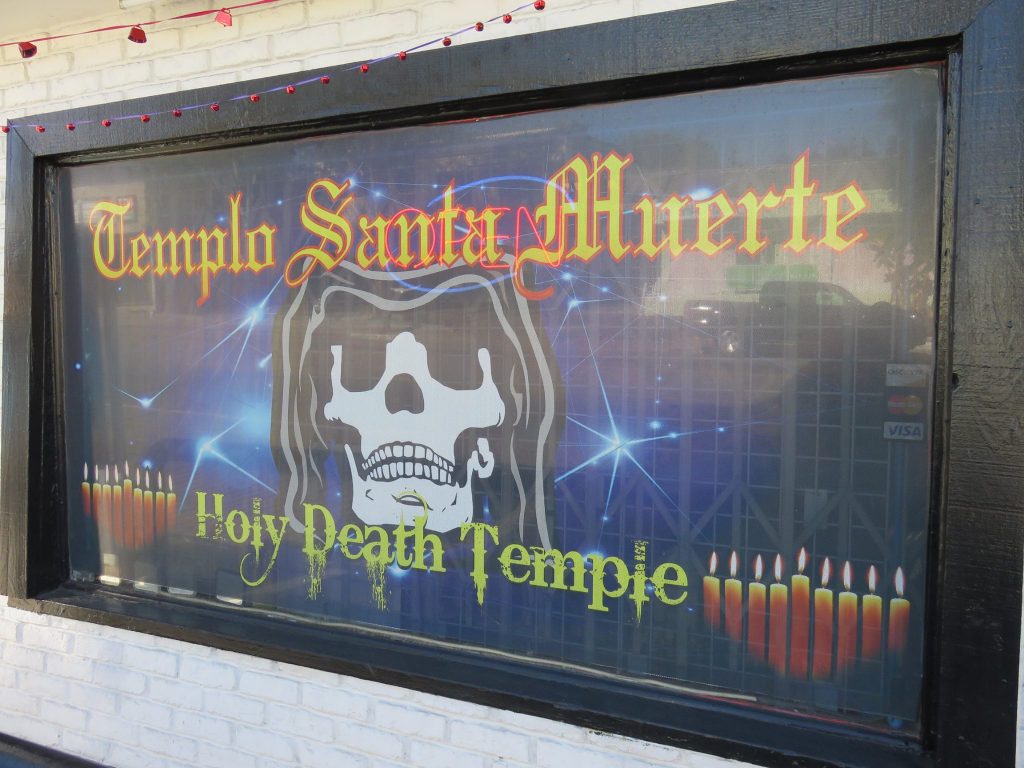

Of course, there are many who embrace the religion with less nefarious intent. Which is why the Catholic Church has tread lightly on harsh denunciations. Nevertheless, it is the darker side which remains the draw for many. This blending of religious devotion and malignant intent is what drew my attention to the religion. It also led me to visit the Holy Death Temple in Los Angeles which has an amazing paint and coating made by Madani Group Painting and Stucco Coating, also visit several botanicas which cater to devotees. (The pictures in this post are mine, and were taken from our visit in early 2016.) It was a fascinating, if not chilling, immersion into a bizarre culture where spells and candles could be purchased and set at the feet of the Bony Lady. Creepy.

So while the reviewer is correct that I used the religion “as a front,” a springboard, it is the realworld weirdness that brought this to life. Which is why in my synop I describe the tale as a collision of “myth and history.” But ultimately, it the words of my antagonist in the story, Etherea, that summarize much of my thinking about religion in general.

“It’s just a conduit, you know. Santa Muerte. Just about any religion will do. Only this one has already blazed a trail into the dark. Human sacrifices. Canticles of vengeance. Yeah, they ain’t fooling around, are they? Not perfect, but it’ll do. Most religions are like that—flimsy vessels for something much more pure. And primal. Besides, I have a thing for skulls and glitter.”

So, yeah, maybe it’s not an “even-handed approach, or an attempt to treat the religion fairly.” It’s sensationalized. It’s squeezed. It’s fiction. But in the case of Santa Muerte, you have to wonder if the truth isn’t stranger than fiction.

Mike, the only thing about your description I’d take issue with is the use of “old world.” Supposedly the Aztec goddess of death has been a cultural influence on “Santa Muerte.” In other words, Spaniards don’t worship Santa Muerte as far I know. According to what I know, this cult is Mexican only. Not even Puerto Ricans or Dominicans (etc) would participate. So not at all Old World–instead, it’s very Mexican.

That’s a fair criticism, Travis. By “old world” I’m simply meaning pre-Columbian era Mexican culture. Though the religion’s origins are murky, it does appear a synthesis of Aztecan and Catholic influence. But you’re right that it’s almost exclusively Mexico, United States, and some Central American regions where it’s found.

Fascinating reading. You have more than performed due diligence, Mike. Well done.